Sharing stage time in Lyric’s early autumn: Vocally splendid Verdi and a fresh ‘Fiddler’

Verdi’s “Ernani,” after a play by Victor Hugo, opened the Lyric Opera of Chicago season in grand fashion with a sumptuous revival of the Scott Marr production. (Cory Weaver photo)

Review: “Ernani’ by Giuseppe Verdi, through Oct. 1 ★★★★; musical “Fiddler on the Roof,” through Oct. 7 ★★★★

By Nancy Malitz

Giuseppe Verdi’s 1844 opera “Ernani” could hardly be conducted, directed or sung more beautifully than it is at Lyric Opera of Chicago, where a quartet of lead singers make some all but impossible scenarios ring true under the leadership of music director Enrique Mazzola and theatrical director Louisa Muller. The sumptuous sets and costumes, designed by Scott Marr, first seen in the 2009-2020 season and further enhanced in collaboration with Muller, are grand in every way.

The opera classic, with an all-American cast of top-flight Verdians, has been sharing stage time with the Broadway musical “Fiddler on the Roof” in a riveting directorial treatment by the Australian Barrie Kosky, who developed it for the Berlin Opera. His “Fiddler” puts the 19th-century story in a 21st-century envelope.

Sparks are flying at the Lyric.

In Verdi’s opera, Ernani’s honor-bound death leaves the young heroine Elvira bereft of the man she loves and facing the likely prospect of a forced marriage to her uncle and guardian Don Ruy Gómez de Silva, the very man who ultimately demands Ermani’s self-inflicted death. Did I mention that Elvira is also sought after by Carlos, the King of Spain, who tried to abduct her? Or that Ernani, the nobly born hero, has.spent a lot of time recently as a bandit?

These are plot elements that would try a modern audience’s patience, were there not also so much heavenly music. And it’s worth recalling that when the opera first appeared, Verdi, inspired by the French romanticist Hugo, was chomping at the bit to break out of old style musical conventions and write radical, plot-driven works.

When Verdi read Hugo’s play, he was enamored of the struggle between love and honor that drives the crazy plot twists. He proposed it to the head of the Teatro La Fenice, praising its “action ready-made.”

Lyric’s solid cast is led by the familiar Russell Thomas, whose darkly burnished tenor lent a conscience-tempering gravitas to the title role from first to last. In Ernani’s own summing up of his impossible situation, his noble birth notwithstanding, he has become a bandit in exile: And if he couldn’t be with Elvira, then he couldn’t go on living.

For her part, the dramatic soprano Tamara Wilson, who starred in Lyric’s “Il trovatore” a few years back, adorned her first number, the cavatina “Ernani involami,” with spectacular coloratura and affecting diffidence, as if she knew her beloved Ernani couldn’t actually whisk her away.

The dramatic baritone Quinn Kelsey has what any actor would rate as the best part in this opera, given that he starts out as the obnoxious Carlo, King of Spain, who presses himself on Elivira and condemns Ernani to death, as dictators are wont to do because they can.

But King Carlo has a change of heart when, in his visit to Charlemagne’s tomb, he overhears the shouts that he is to be the next Holy Roman Emperor. Overwhelmed and humbled, he vows to pardon the conspirators and let the lovers follow their hearts. The enormous scene of exhilarating lows and highs is Kelsey’s triumph, the evening’s tour de force. Lyric Opera should make him the house bad guy. Oh wait. Maybe he already is. Kelsey’s been at Lyric in 18 roles since 2003, the program book says.

Bass-baritone Christian Van Horn, another Lyric veteran, arrived at the house as a Ryan Center artist-in-training in 2004 and has gone on to a major career. HIs character, de Silva, gets killed off in the Victor Hugo play. Verdi let him live, an idea that a lot of people might conceivably object to; the playwright certainly did. Given Van Horn’s impeccable singing, it seemed right to let him survive.

On the other hand, as the philosophical milkman Tevye so often says in “Fiddler on the Roof,” Barrie Kosky’s novel 2017 conception of the 1964 musical is a remarkabe creation by any measure. But this Lyric premiere arrives with special poignancy given current events in Eastern Europe: Though subject to curtailments at the whim of the Russian tsar in the early 1900s, the plucky but impoverished Jews in the tiny stetl Anatevka (very near Kiev) have been allowed to eke out their livelihoods within the restricted borders of the Pale of Settlement, a designated Jewish area in the Ukraine.

The musical is based on a stetl tale by Yiddish story-teller Sholem Aleichim. It first starred Zero Mostel as the head of a large family with daughters of marriageable age but single-minded hearts. The huge hit ran for nearly 10 years on Broadway, and won nine Tonys including best musical. It went on to enjoy five Broadway revivals, and in 1971 it was made into a film starring Chaim Topol. Jerry Bock wrote the rambunctious music, with rustic lyrics by Chicago-born Sheldon Harnick, and a haunting storyline by Joseph Stein.

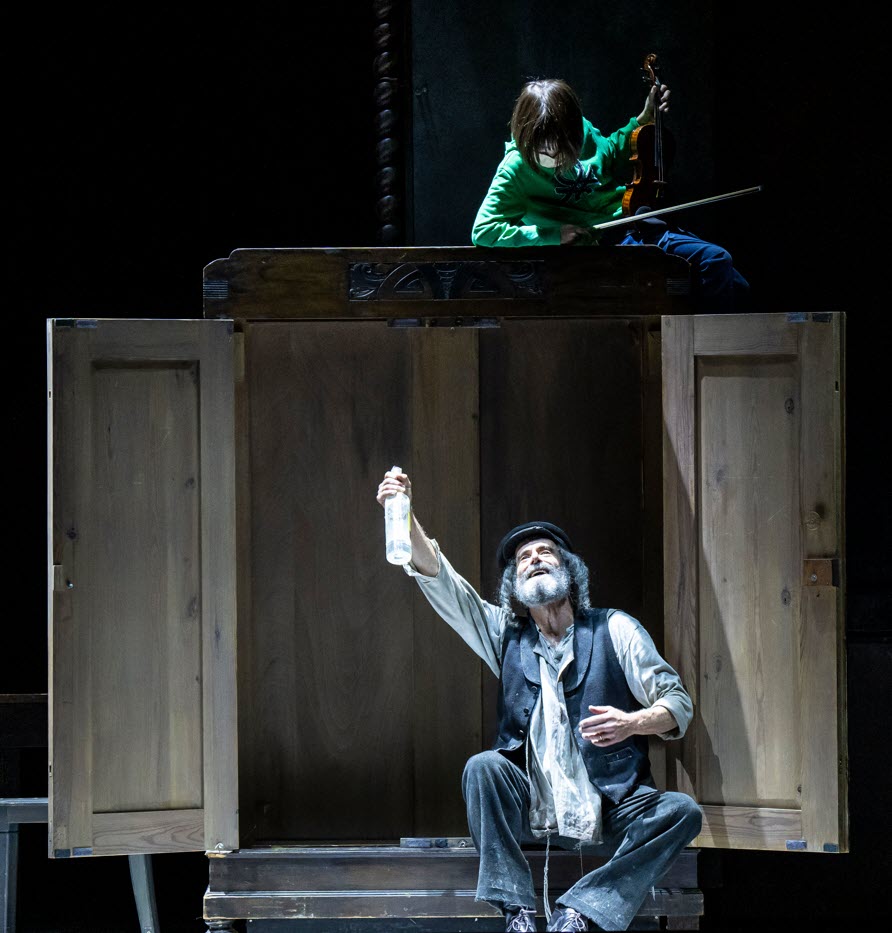

A curious fiddler from the present day (Drake Wunderlich) discovers the poor milkman Tevye (Steven Skybell) in the beloved Old World musical “Fiddler on the Roof.” (Todd Rosenberg)

Kosky’s fresh treatment, first seen at Berlin’s Komische Oper, is a charmer that opens with a boy in modern dress rolling in on his scooter to espy a neighborhood of cabinets and cupboards in a puzzle-box array. Casing the area with dispatch, he opens one cupboard to discover a violin and hesitantly begins noodling the fiddler tune. (Chicago fifth-grader Drake Wunderlich, who scooters into this scene, is the astoundingly able fiddler here.) Villagers climb out of cubbyholes and pop out of closets to begin their daily labors.

Rufus Didwiszus’ charming stacked-cubbyhole design suggests the makeshift life of these stetl dwellers, whose right to live in Anatevka is ever subject to the tsar’s whim. (Lyric photo)

The shabby charm of this “Fiddler” ‒ the fragile portability of its set boxes ‒ is a delight, if gently sobering: The tsar’s threat is keenly felt. The cubbyhole hideouts, which seem to look different every time I peered at them, did put me in mind of a bizarre story that the Soviet-era composer Dmitri Shostakovich used to relate, about a brutal period in his early forties when he landed on Stalin’s bad side for the second time during the tyrant’s reign of terror. Suddenly in mortal danger, with a pregnant wife to protect, Shostakovich kept his suitcase within reach at all times, and he slept nights in a stairwell.

Despite this gray reality, Lyric’s “Fiddler” is a light-hearted tale at the onset, even as one daughter after another petitions their baffled father Tevye (Steven Skybell) to let her marry the one she loves rather than someone chosen for her.

The challenge startles the money-minded matchmaker Yente (Joy Hermalyn), not to forget Tevye and his practical wife Golde (Debbie Gravitte). Marrying for love? Whoever heard of such a thing? Tevye and Golde’s showstopping duet, “Do you love me?” “Do I what?” ensues, as the long-married couple ‒ parents to daughters Tzeitel, Hodel, Chava, Shprintze, and Bielke ‒ ponder this novel concept.

The veteran Broadway conductor Kimberly Grigsby kept the show rolling, though at times allowing the singers’ indulgent pauses and exaggerations to a fault. But one can sympathize: This story is huge, big-hearted and unwieldy, an irresistible dive into an angst-ridden dream. When in touring musicals does one hear an orchestral sonority as plush as the one emanating from Lyric’s pit? Or the amplitude of such a chorus in that lively acoustical space?

Otto Pichler’s terrific dance numbers (revived for Lyric by Silvano Marraffa) put one in mind of the electric abandon that energized the Grambling step dance scene at Lyric in last season’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” This time, the priceless number is a deliriously over the top bottle dance starring a riotously leaping band of wedding revelers. I for one would have been happy to watch them do it all over again.

Related Links:

“Ernani” performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

“Fiddler on the Roof” performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com