Muti’s crowning year as CSO music director begins with a flourish, and more is just ahead

Conductor Riccardo Muti and pianist Yefim Bronfman share the ovation for their Brahms. (Concert photos by Todd Rosenberg)

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Riccardo Muti; Yefim Bronfman, piano. Sept. 22 at Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Riccardo Muti’s farewell tour as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, off to a rewarding start in the opening weekend of his 13th season at the helm, continues in classic Muti fashion Sept. 29-30 and Oct. 1 with a program of Rossini, Mozart and Prokofiev. It is indeed a tour, albeit in the single locale of Orchestra Hall, of the grand traditional repertoire for which Muti has long been celebrated and much of which CSO audiences experienced in his first dozen seasons.

Whereas the coming series of concerts will spotlight the 81-year-old maestro and the orchestra he has honed to peak sensibility and finesse, the season opener on Sept. 22 topped out in a collaboration with pianist Yefim Bronfman in Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor. Allowing that a “definitive” account doesn’t exist in the universe of the performing arts, we surely might hedge with the word consummate in describing the musicianship, poetics and interpretative authority on display in that splendid and riveting Brahms.

It’s astounding to think that the D minor Piano Concerto was conceived by a 21-year-old composer, even if its working out occupied him to the ripened age of 25. The grandeur of Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat notwithstanding, an excellent debate could be engaged over whether the D minor might be the greatest piano concerto ever penned by anyone, Beethoven included.

The four-movement Second Piano Concerto has been characterized as a symphony with piano obbligato, but the youthful Brahms in fact briefly mulled the materials of the first concerto as the stuff of a first symphony. The shadow of Beethoven loomed far too great, however; it would another two decades, when Brahms was in his forties, before he offered his First Symphony for the world to judge.

Bronfman’s eloquent and technically dazzling turn through the D minor, playing as remarkable for its subtlety as for its power and brilliance, made one wonder whether Brahms, himself the soloist in early performances, must have been a pianist of like prowess and kindred sensibility. The opening movement, with its ferocious orchestral expostulations answered ever so gently by the piano, puts one in mind of the slow movement of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto, famously likened to a dialogue between Orpheus and the Furies.

Brahms’ own slow movement brings the piano into exquisite prominence, as if in accompanied soliloquy. The finale is a bravura romp. Turn by turn, Bronfman, like a masterful actor, rendered the music and the interpreter one and the same in a performance as songful as it was ultimately heroic. Muti, as interlocutor, kept the orchestra in taut connection with the pianist: arguing, contemplating, soaring with him.

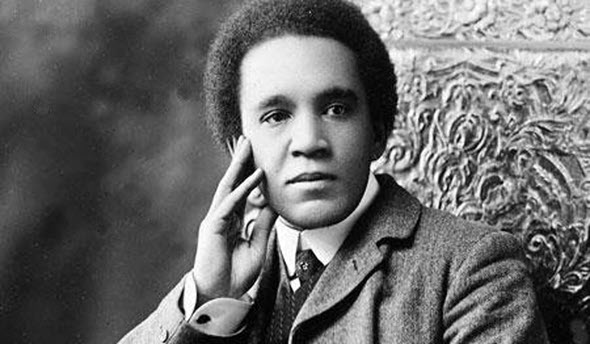

The concert opened with the long-deferred U.S. premiere of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s “Solemn Prelude,” a gorgeous 10-minute essay composed in 1899 and sounding in every measure like a distillation of its time. British and Black, Coleridge-Taylor was 24 years old when he wrote his “Solemn Prelude,” which displays both his own mastery of the orchestra and his consciousness of, well, everything going on around him in that teeming era of post-Romanticism.

One might enumerate the influences: Franck perhaps first of all, but also Elgar, Saint-Saens, Tchaikovsky. And it’s worth noting that Sibelius’ First Symphony and Schoenberg’s “Verklärte Nacht,” two heatedly Romantic essays, also date from 1899. But the young Taylor-Coleridge was already his own man. The “Solemn Prelude,” marvelously layered and textured, employs the rich palette of the late 19th-century orchestra with a confidence and variety worthy of Mahler or Strauss. It’s showcase stuff for the Chicago Symphony, and Muti led a luxurious, finely contoured performance.

To cap the evening, Muti turned to early Tchaikovsky, the Symphony No. 2 in C minor, dubbed the “Little Russian” for the folk tunes it incorporates from Ukraine, long known as “little Russia.” Stravinsky was famously fond of the Second Symphony, which he loved for its untrammeled Russian authenticity – before Tchaikovsky bent his symphonic style toward the European (meaning Austro-German) model.

Had I grown up in Russia, I might share that view. But as it is, I have always found the early Tchaikovsky symphonies to suffer from a directness that I cannot distinguish from shallow simplicity. The music is indeed colorful, mainly buoyant and lyrical. It also tends to repetition, not least in the finale, of which Tchaikovsky was particularly proud. No doubt the composer would have been delighted by Muti’s sympathetic reading and the CSO’s splendorous playing. Me, I’m looking forward to Prokofiev’s edgy, rigorous and blazing Fifth Symphony on the program just ahead.