Opera bio-drama ‘Fire Shut Up in My Bones’ throws heat as it casts a spell on Lyric stage

In “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” Charles (Will Liverman, left) recalls how Uncle Paul (Reginald Smith, Jr.) shared home-grown wisdom when “Char’es-Baby” (Benjamin Preacely, center) was just a sprout. Charles’ spirit angel (Brittany Renee) watches. (Todd Rosenberg photos)

Review: “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” Music by Terence Blanchard, libretto by Kasi Lemmons, at Lyric Opera of Chicago through April 8. ★★★★★

By Nancy Malitz

The Lyric Opera of Chicago has had its share of tough breaks in recent years, with ambitious projects felled by Covid including an international Wagner “Ring” festival that had been many years in the making. But what this determined company has accomplished since then is balm to the soul in an uneasy world.

On the boards now through April 8 is a stunning success, a not-to-miss opera with a magnificent heart, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” It’s also available for streaming as long as you buy a ticket during the run.

There are so many ways this show is a rarity that it’s hard to find a place to start. It’s as grand as a grand opera can be, and yet it’s in English, and thoroughly American, requiring no knowledge of royal bloodlines or anything European. Its dance scene is a show-stopper, but there’s not a toe-shoe in sight. There’s a chicken-plucking scene and a frat-house hazing, and the starring dramatic soprano plays an exhausted mother of five.

Best of all, the lush, richly chromatic and, one might even say Romantic, music flows from the pen of the great jazz trumpeter Terence Blanchard, who at 60 now has two operas under his belt and seems raring to go for more. His first opera “Champion” tracked the arc of welterweight fighter Emile Griffith from world champ into the dementia commonly called boxer’s brain. “Champion” premiered in 2013 at the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, which devotes itself to new work development. That company’s premiere of “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” came in 2019.

Larger opera houses including the Lyric also took notice. This co-production of “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” is shared with the Metropolitan Opera, where it sold out last fall, and the Los Angeles Opera, which plans a future run. The show is first class in every way. It’s arrival put me in mind of another breakthrough event at the Lyric, back In 1999, when “A View From the Bridge,” with music by William Bolcom and a libretto by Arnold Weinstein and playwright Arthur Miller, would unfold.

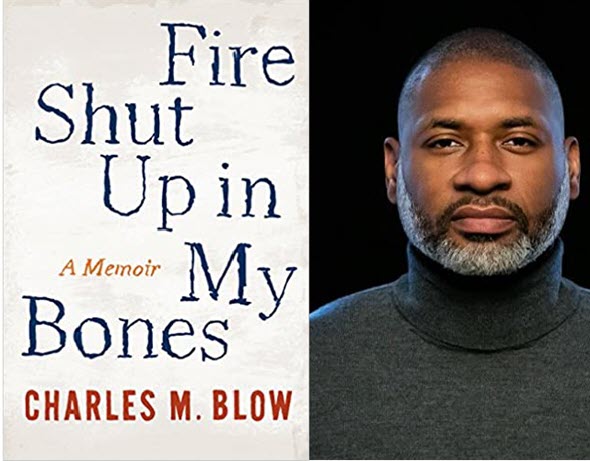

An all-Black cast presents this coming-of-age spellbinder based on the harrowing memoir of the same name by New York Times columnist and TV commentator Charles M. Blow, who grew up in the Deep South. The tale begins as Charles, fresh out of Grambling State University, heads home with a gun in hand and burning with fury, intent on payback for the damage done to him as an innocent child.

Charles’ redemptive journey is the stuff of Blanchard’s big-hearted opera. Its swiftly moving structure is shaped by librettist Kasi Lemmons, who has a fine ear for language and a solid background in television and film. Each scene knows exactly what it’s about, and the treatment simmers with latent power of something suggested, as opposed to merely told.

The working out of Charles’ torment comes as he confronts his troubled childhood memories. Blanchard’s music, achingly cathartic, is colored in chromatics, and it is idiomatic of classical, soul, gospel, jazz, and even, gloriously, step-dancing as the occasion warrants.

By turns suspenseful, ruminative, heartbroken, even reverential, Blanchard’s characteristic style often seems like melody thinking itself up on the spot. If you’re wondering whether a jazz composer can soar in opera, the answer is yes.

On his visit home, young adult Charles sees his childhood self in flashbacks. (High-voiced Benjamin Preacely plays the boy everybody calls “Char’es-Baby” with a poise well beyond his fifth-grade years.) Char’es-Baby was mostly ignored by four rambunctious older brothers, despite his efforts to tag along. The priceless scenes include a chicken-plucking factory that employs his long-suffering mom, Billie, who tries her best. With Charles, we relive the many times that trouble unfolds.

Charles’ imaginary and more-or-less constant companions are the spirits called Destiny and Loneliness, and later Greta, a love interest, who is real. All are made mysteriously seductive by soprano Brittany Renee. These three figures reflect various forces that shape the boy. There are also feisty scenes between Char’es-Baby’s mother and his spendthrift father, who oozes charm when he touches his wife for a few bucks on her chicken-factory paydays.

Teen Charles has a tentative romantic fling with a local girl, but even so he struggles to accommodate the shame of the violations he suffered at an age too young to fully understand, at one point seeking the pentacostal purge of baptism. The nature of Char’es-Baby’s heart-breaking abuse is only alluded to, and Blanchard’s unforgettable music does the rest.

Two of the leading roles, in Chicago as at the Met, are taken by baritones who got their start as young artists at the Lyric’s Ryan Center. Will Liverman is alternately tight with fury and consumed with longing for resolution as Charles, the hot-headed young adult determined to avenge the damage of his childhood. It’s a magnificent performance. Chris Kenney also excels as the casually opportunistic older cousin Chester, who betrayed Char’es-Baby those years ago. Both are impressive baritones who fully inhabit their characters – one positively transformed by circumstance, the other still shiftless.

Soprano Latonia Moore is a standout as Char’es-Baby’s’ remarkable mother Billie, who manages five boys while barely hanging on. Tenor Chancey Packer aptly plays the kind of a guy you love to hate – Spinner, the compulsively straying husband who causes Billie no end of heartache. But Billie’s response is a true-grit aria, “Sometimes you gotta leave it in the road,” an anthem for moving on with life no matter what is thrown your way. Moore’s delivery was sublime.

Co-directors James Robinson and Camille A. Brown (who is also the choreographer) birthed this original concept at the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, and it’s filled with electric moments, foremost among them an exuberant step-dance number of dizzying length that depicts Charles’ painful fraternity paddle-hazing at Grambling State University. The scene had the delighted opening night Lyric crowd in a stomping ovation. Conductor Daniela Candillari is a major talent who clearly has a gift with new works; she aptly led two operas on smaller stages for the Chicago Lyric in previous years, and she made her Met debut earlier this season in Sarah Ruhl and Matthew Aucoin’s “Eurydice.”

The idea of a “fire shut up in my bones” comes from the biblical lamentations of Jeremiah, who speaks of “a fire burning in my heart, imprisoned in my bones.” It’s as good a name as any for the suffering of Char’es-Baby, whose casual abuse suffered at the hands of an older cousin was so unspeakable to him as a child that it remained a still-burning secret from the elders he adored.

Among those treasured elders is his Uncle Paul, a tiller of the soil and spinner of homegrown philosophy that nourished the boy when he was just a sprout. Another is, of course, his mother, whose wisdom is simple but pure, and it becomes a lesson that the boy is able to adapt for his uncle’s benefit in a time of need: “Sometimes you gotta just leave it, You gotta just leave it alone, You gotta leave everything you don’t need, You gotta lay it down and leave it in the road.”..

Allen Moyer’s mood-shifting set is state of the art. It makes use of large boxlike cuboids that glide around and accept film projections as Charles’ memory summons one scene or another. There’s a shimmering forest where teen Charles is initiated by his girlfriend into love; the textured interior of Billie’s coarse-wood home; a bar where Billie’s no-account husband hangs out, and other fraught places in Charles’ turbulent memory. It’s a ballet of memories that flow into each other as Charles’ intense recollections collide.

“Fire Shut Up in My Bones” tells a hardscrabble story of a young man who encountered just enough luck and love to let his innate brilliance find its way. Author Blow is now 51. Librettist Lemmons is 61. Composer Blanchard is 60. They have created a brilliant piece of gentle wisdom that will endure. It’s our luck if they are just getting started. Watch the composer and the star singer talk about this project below.