Portrait for violin and piano: Astor Piazzolla’s lifelong musical arc from Bach to Grand Tango

Pianist Jun Cho and violinist Philippe Quint played works by Piazzolla and composers he admired. (Photos courtesy North Shore Chamber Music Festival)

Review: “Astor Piazzolla Centennial Celebration.” Philippe Quint, violin; Jun Cho, piano. At Pianoforte Chicago.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Just as he holds a central place in the modern history of tango, Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla has always inspired a certain fascination in the realm of classical music. Indeed, the young Piazzolla imagined himself heir to the musical tradition of Stravinsky and Bartók, and it took the perceptive intervention of the great French pedagogue Nadia Boulanger to help the aspiring composer find his true voice in the accents, rhythms and passion of the tango.

The circuitous path that Piazzolla blazed, and the diverse influences he absorbed throughout his creative life, was cleverly and persuasively traced in a lecture-recital by violinist Philippe Quint with pianist Jun Cho on Nov. 27 at Pianoforte Chicago, in a presentation of the North Shore Chamber Music Festival.

Piazzolla (1921-92), a native Argentine, gravitated to the tango culture at an early age. But this prodigious musician was also a musical sponge whose head was soon turned by what he perceived as the “higher” art of European classicism.

Thus violinist Quint, whose virtuosity and personal immersion in the tango idiom illuminated Pianoforte’s intimate recital space, began his neatly framed narrative where Piazzolla had begun — deep in the tango milieu in which he grew up, but also with the siren song of European classical music in the air. Most of the program consisted of arrangements by Quint or others.

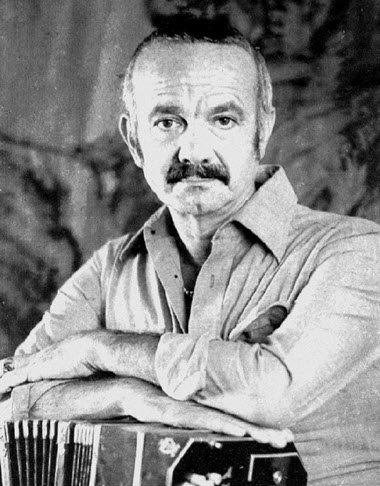

Throughout the presentation, which felt more like a personal appreciation than a lecture, Quint and Cho indulged both Piazzolla’s questing spirit and his imaginative music while displaying a level of technical mastery equal to the broad scope of their stylistic canvas. But as much as anything, it was Quint’s charming manner, mellifluous voice and solid historical grounding that made the event so thoroughly engaging. Projected photos of Piazzolla and the great artists who touched his life added immediacy to the story.

A sequence of Carlos Gardel’s tango-ballad “Por una Cabeza” and Alberto Ginastera’s Three Pieces for Piano, No. 1, pointed up the dual magnets that pulled at the gifted young composer and master of the bandoneon, the large accordion-like instrument that lies at the heart of tango. From the elastic rhythms and sensual expression of Gardel’s tango, Quint and pianist Cho made the great stylistic leap to the Argentine Ginastera’s rhythmically incisive but classically formal Prelude — the very definition of young Piazzolla’s dilemma.

To underscore the allure of Western art music, the duo then offered up a vituosic arrangement of the Scherzo from Stravinsky’s ballet “The Firebird,” followed by three of Bartók’s Romanian Dances with their charged rhythms and brash harmonies. The fire and drive that Quint and Cho brought to Bartók’s spin on these folk dances produced a highlight of the recital.

But perhaps the single most fascinating episode consisted of three pieces that touched on Piazzolla’s encounter with Boulanger in Paris. He took her his Prelude No. 1, a well-made piece studiously crafted in a sort of neo-classical mold. Boulanger acknowledged the merit of the work, but noted that she did not hear Piazzolla’s distinctive voice in it. Quint and Cho followed this with Boulanger’s own Cello Piece No. 3 — then Piazzolla’s “Tango Triunfal,” which sounded like a riff on Boulanger’s work. The composer who would become a paragon of tango artists was still finding his way.

Something of a side trip to Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood,” maybe not the evening’s most idiomatic display, referred to the jazz influence on Piazzolla — illustrated beautifully indeed by a diaphanous and languid account of his iconic “Oblivion.” Another intriguing matchup ensued when Quint and Cho delivered a closely articulated performance of the first movement of Bach’s Sonata No. 4 for violin and keyboard followed by Piazzolla’s remarkably Baroque “Muerta del Angel.”

Quint’s biographical journey ended on a mountain top, with Piazzolla in full voice — one very much his own. The consummating work was Le Grand Tango, a masterpiece of many stylistic elements subsumed within the texture and pulse and soul of tango. Quint didn’t mention who made the arrangement for violin and piano, but there it was in the program, and it spoke volumes about the esteem in which Piazzolla is held today. The composer who put her own hand to Le Grand Tango was the celebrated Russian Sofia Gubaidulina.