Scaling ‘Messiah’ back to its Baroque origins, Bella Voce frames oratorio with style, clarity

In the intimate acoustics of church sanctuaries, Bella Voce has found an ideal frame for its precise, Baroque-scaled approach to Handel’s ‘Messiah.’

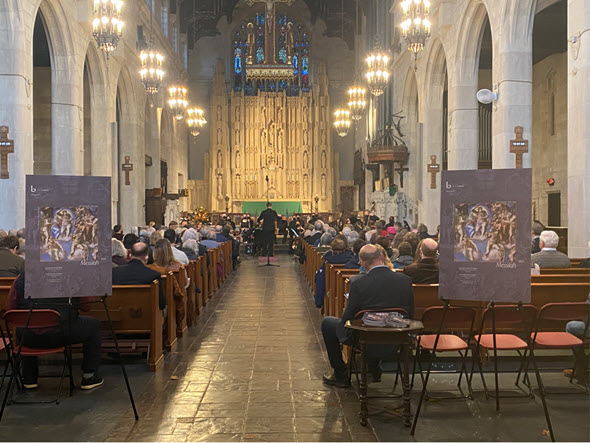

Review: “Messiah” by G.F. Handel, presented by Bella Voce at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Evanston.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Still caught up as we are in the Victorian perspective on Handel’s “Messiah” as a grandiose spectacle requiring performing forces worthy of that ideal, we tend to forget the time, place and musical aesthetics of its origin: that it was composed in 1741, a product of the High Baroque, and that every musical phrase and expressive gesture of this epic oratorio bespeaks its provenance. It was little short of wonderful to be reminded of Handel’s “Messiah,” as opposed to Queen Victoria’s, in a stylishly detailed, intimately framed and yet quite magnificent account by the Chicago choral ensemble Bella Voce.

The Nov. 21 performance led by Andrew Lewis took every advantage of its setting – the long, vaulted shoebox space of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Evanston, where warm, precise acoustics illuminated the singing of a 22-voice choir and cast a supporting chamber orchestra in high relief. Handel’s wealth of arias and duets was spread among the choristers, and each such spotlighted number offered further testimony to Bella Voce’s thoroughgoing excellence.

Speaking of numbers, there are 53 in a complete excursion through “Messiah,” and while most performances make trims, every single movement was embraced here in a production that ran nearly three hours, including a 20-minute intermission. But the evening seemed to fly by musical delights tumbled forth one upon another, an unflagging series of smartly prepared arias and choruses, from first to the very last – an imposing, crystalline turn through Handel’s brilliant fugue setting of the work’s capstone Amen.

Indeed, Handel’s freshened and energizing counterpoint shone everywhere in the crisply etched lines Lewis drew from his small chorus. The conductor’s generally brisk tempos, combined with the agility of his modest forces, purged “Messiah” of the artificial grandeur to which it is so often subjected. If a surprisingly quick “For Unto Us a Child Is Born” might have caused one to blink, the clarity of the choral singing and Lewis’ propulsive rhythm soon made the tempo seem right.

Other great and very familiar choruses – among them “All We Like Sheep,” “Lift Up Your Heads,” and certainly “Hallelujah” and “Worthy Is the Lamb” – rang new and bracing.

In that intimate space, and against the musical backdrop of the chamber-scaled chorus, Handel’s many reflective arias acquired a sparkling intimacy. Soprano Hannah de Priest’s bright, liquid “Rejoice Greatly” was one of several arias that basked in concertmaster Martin Davids’ eloquent violin accompaniment. Countertenor Thomas Alaan and soprano Henriet Fourie imbued “He Shall Feed His Flock” with lullaby gentleness. Bass Eric Miranda and trumpeter Josh Cohen collaborated on a turn through “The Trumpet Shall Sound” of heroic proportions.

The dramatic summit of “Messiah” is surely the lamentation for solo alto “He Was Despised,” which in a masterstroke of theatrical irony Handel and librettist Charles Jennens placed just after the aspiring chorus “Behold the Lamb of God.” Anna Vanderkerchove brought a profound sensibility and glorious voice to this consummate image of alienation.

As a group, the soloists embellished Handel’s vocal lines with creative ornamentation, and Lewis’ band sounded fully at home on period instruments. When the last trumpet had sounded and the Amen fugue had rent the air, the audience made a sustained and joyful noise of its own.