‘Fannie’ at Goodman: In narrative and song, recalling the heroism of an unlikely activist

Review: “Fannie: The Music and Life of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Cheryl L. West, at Goodman Theatre through Nov. 24. ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

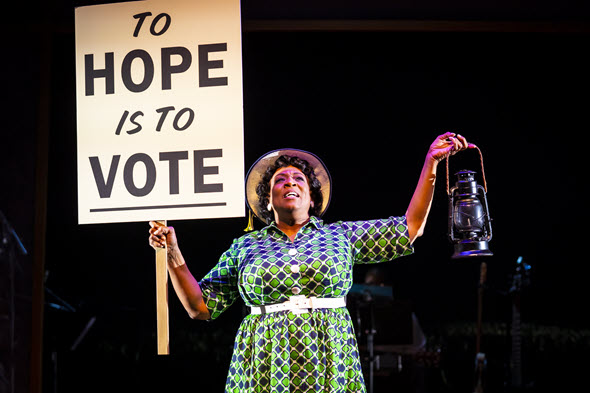

E. Faye Butler’s one-woman performance as Fannie Lou Hamer, the daring and stalwart champion of Black voting rights in America’s tumultuous 1960s, is rich in memorable vignettes, just as the song-laden show abounds in energy, wit and aspiration.

But the interlude that really gets at what the courageous and remarkable woman was about, what she was up against, comes in Butler’s account of a brutal beating Hamer endured at the hands of the police, out of public view and beyond accountability, when she was jailed on flimsy charges that basically stood for her double offense of being Black and pushing for the right of Black people to vote in the United States.

“Fannie: The Music and Life of Fannie Lou Hamer” is the beguiling and entertaining and sobering theatrical creation of Cheryl L. West. It generously incorporates spirituals, sometimes as sources of inspiration, other times as balms and more than once as a familiar hand to hold under extreme duress. But the show is the farthest thing from a jukebox revue. “Fannie” stands solidly and compellingly on the eloquence and clear-sighted arc of West’s text, which Butler brings vibrantly, lovingly to life in a turn as irrepressible as it is coherent and credible.

Fannie Lou Hamer was born in Montgomery County, Miss., in 1917. She died in 1977 at age 59. Her entry into the civil rights movement was belated: When she was 45 years old, she tried to register to vote, only to be rebuffed by tests of knowledge and literacy established expressly to prevent Blacks from voting – a pretty sure blockade since Blacks in the deep South were generally denied the educational advantages of white children. But Hamer was determined to vote and, after taking the literacy test three times, prevailed. Her personal campaign set the stage for what would become her crusade to enable all Black people to exercise their Constitutional right to vote. Hamer’s perilous enterprise, against overwhelming odds, is the narrative of “Fannie.”

Butler’s infectious portrayal is lifesize and then some. She commands the stage as fully and grandly as she inhabits the character of this seemingly ordinary woman who found something extraordinary within herself. Chicago audiences may know Butler best for her vocal prowess, and that voice comes powerfully, gloriously into play here. The many songs of hope and spirituality woven into “Fannie” reflect the importance of singing in the campaigns of the historical figure.

Hamer was famous – and beloved – for being ever ready to add her potent voice to church or community choirs wherever she turned up to advocate, cajole and encourage. Butler uses song to always arresting dramatic purpose, whether whispering a line in reassurance or belting out the gospel according to Fannie. A small band of backup musicians propels the music forward, sometimes even adding vocal support.

Like all political theater, the tension here resides in the moment, not in the arc. We know where this is all going, this sequence of historically documented tableaux. The fascination lies in Butler’s deeply personal reincarnation of Hamer’s journey, step by visionary step, blow by shockingly vivid blow.

Henry Godinez’s seamless direction is no doubt reflected in the continuity, the theatrical integrity, of Butler’s performance. Collette Pollard’s spare, pragmatic set design has assorted props in easy reach and allows Butler a chance to sit from time to time. But in this kinetic 90 minutes, sitting is not where the action is.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com