Ron Parson, steeped in Wilson’s stagecraft, brings theater perspective to seminar series

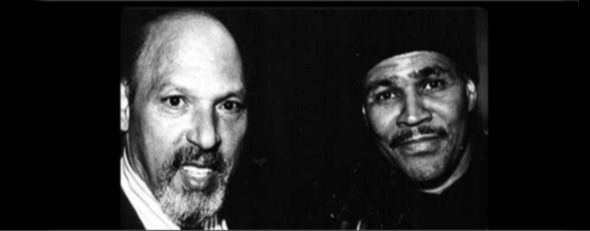

On the subject of August Wilson, left, Ron OJ Parson is a contemporary master.

On the subject of August Wilson, left, Ron OJ Parson is a contemporary master.

Preview: Four-part online presentation from Court Theatre offers insights the director gleaned in 31 productions of August Wilson.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Ron OJ Parson was all set to direct August Wilson’s play “Two Trains Running” at Court Theatre this fall when the pandemic added that plan to the numberless others it has sent off the rails.

When Parson, a Court resident artist since 2008, is finally able to stage “Two Trains Running,” it will complete his traversal at Court of all 10 of the plays in Wilson’s Pittsburgh cycle of dramas that, decade by decade, reflect the African American experience in urban America through the 20th century.

Jacqueline Williams as the ancient Aunt Ester and Alfred H. Wilson as Solly Two Kings in “Gem of the Ocean,” directed by Ron OJ Parson at Court Theatre in 2015. (Michael Brosilow)

“Wilson was a poet. All his language is poetic,” said Parson, who will bring his broad experience with Wilson’s plays to a four-week online seminar series dealing with the playwrights craft and his place in African American culture. “I always go back to things being spiritual. You don’t have to act in an August Wilson play – you feel it in your gut.”

Parson has helmed 31 productions of Wilson’s Pittsburgh plays at theaters around the country. It’s safe to say he knows the Wilson canon as intimately as anyone in the game. The director teams up with University of Chicago professor Kenneth Warren in the seminars collectively titled “The World of August Wilson and The Black Creative Voice” and scheduled to begin Sept. 8.

The four weekly discussions, which also can be streamed after their debut dates, will unfold through “The Great Migration” (first offered Sept. 8), “The Civil Rights Movement” (Sept. 15), “Genealogy and Tradition” (Sept. 22) and “The Ground on Which I Stand” (Sept. 29). See ticketing details here.

Parson will participate in the final segment, based on a celebrated speech Wilson gave in 1996 in which he argued for the integrity, independence and unique worth of Black theater.

Parson: “These plays are about human beings going through something that is affected by the world we live in.”

“These plays are about human beings going through something that is affected by the world we live in,” Parson said. “Wilson was writing about what those external things do to us, but the plays are also about family from the inside. In that sense, they are universal, which is why all kinds of audiences respond to them.”

The first Wilson play that Parson staged at Court, in 2006, was “Fences,” set in the 1950s. The director said the idea of doing the play met with the same resistance then that he has seen almost everywhere he has proposed staging this winner of the 1985 Pulitzer Prize about a bitter ex-baseball player who feels he was denied a chance at the big leagues because of his race. The old ballplayer and his adolescent son are on different wavelengths.

“I still get that reaction of uneasiness about ‘Fences,’ like it’s maybe not right for this or that theater’s audience,” Parson said with a small laugh. “Now I just say, trust me, it will be fine. And it always is because it’s a universal story.

“In a Q&A after (the Court) production of ‘Fences,’ a Chinese woman spoke up – in very broken English – and said, ‘That’s my family. My husband and my son had these issues.’ Great plays work across cultures. Lorraine Hansberry (“A Raisin in the Sun”) said she was influenced by Sean O’Casey’s ‘Juno and the Paycock’ (about the tensions within an Irish family).”

Booster (Anthony Fleming III) confronts his father (A.C. Smith) in Wilson’s “Jitney” at the Court in 2012.

In the order of their premieres, “Fences” was the third of Wilson’s 10 Pittsburgh plays. (Actually, only nine are set in Pittsburgh, where Wilson grew up. The second play, “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” dealing with the 1920s, takes places in Chicago.) Two of the plays had their world premieres in Chicago at the Goodman Theatre, — “Seven Guitars,” set in the 1940s, and “Gem of the Ocean,” set in the 1900s to commence the epic.

The remaining installments are “Jitney” (set in the 1970s), “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” (1910s), “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” (1910s), “The Piano Lesson” (1930s and winner of a second Pulitzer Prize), “King Hedley II” (1980s) and “Radio Golf” (1990s).

Wilson’s plays are addictive in their melding of vivid characters, earthy naturalism and a lyrical writing style evocative of Tennessee Williams. From “Gem of the Ocean” to “Two Trains Running” to “Radio Golf,” the experience from the seats is like Aeschylus meets Shakespeare, this potent merger of timeless wisdom and authentic human portraiture.

“People ask me if I don’t get tired of doing them,” Parson said. “But it’s never the same experience, even with the same actors. And actors will tell you it always difference for them, too. The more often you connect with these plays, the more they reveal.”

Parson was on hand at the Goodman during what he remembers as the feverish run-up the world premiere of “Gem of the Ocean.” He spent some time with Wilson and finally asked him how he did what he did with such phenomenal clarity and grace.

“He said, ‘I listen to the voices. They speak to me.’”

King Hedley II (Kelvin Roston Jr., left) and his pal Mister (Ronald L. Conner) hope to pool enough money to open a video story in Wilson’s play set in the 1980s.