‘Oedipus Rex’ at Court: The eternal conflict of fate versus free will, held up to drama’s glass

King Oedipus puts out his own eyes upon grasping the hideous truth of his crimes. Innocent daughter Antigone (Aeriel Williams) is among those who suffer. (Photos by Michael Brosilow)

“Oedipus Rex,” by Sophocles, in translation by Nicholas Rudall, directed by Charles Newell. At Court Theatre through Dec. 8. ★★★★

By Nancy Malitz

As we sit in the small, semicircular, arena-style stage at Court Theatre in Hyde Park, where Sophocles’ ancient drama “Oedipus Rex” unfolds, the audience becomes part of an urgent thriller. Actors prowl the aisles, murmuring that our city Thebes is sinking under “waves of death.” Plague and pestilence have left people terrified.

The explanation for this catastrophe? Unknown. Desperate citizens implore their intrepid king, Oedipus, to figure out what’s going on.

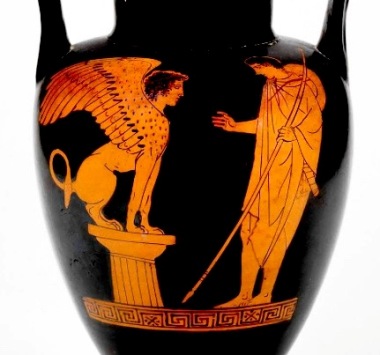

As portrayed by Kelvin Roston, Jr., one of Chicago’s most explosive actors, brave Oedipus knows he is the obvious choice to rescue Thebes. It was he alone who outwitted a sphinx that menaced the city several years back – a ravenous beast devouring anyone unable to solve her riddles. Clever Oedipus vanquished that monster and became husband to Queen Jocasta, with whom he has sons and daughters. This still youthful king and undisputed hero rules with magisterial pride.

Now Oedipus is tasked with finding the cause of Thebes’ new devastation. He vows avenging wrath upon those responsible, and thus begins Court Theatre’s year-long project to present the impressive 2,500-year-old trilogy of surviving Oedipus-related tragedies by a celebrated tragedian of classical antiquity.

In the first installment, Oedipus will struggle with an oracle’s dread revelation that the cause of Thebes’ misery is a man who has murdered his royal father and defiled the bed of his mother. As harrowing details of Oedipus’s unknown past begin falling into place, the evidence points more and more to the Theban king himself.

Yet honorable Oedipus pursues the matter aggressively. He takes action, fiercely chasing down the truth, following clues from his brother-in-law Creon (Timothy Edward Kane), various seers and messengers and shepherds. Oedipus’ wife Jocasta (Kate Collins, in a roller-coaster ride of accelerating anxiety) becomes so alarmed that she begs the king to abandon the quest.

What unfolds is a touching, many-sided portrayal of human peril and an essential conundrum: If Oedipus’ crime, unknowingly committed, is ordained by fate and a thing for which he and his children must suffer, then is Oedipus really guilty? Or free at all? Wendy Robie and Stef Tovar, as individual shepherds brought in to shed light at two different stages of the investigation, epitomized the common people’s reluctance to do any harm to a king of such clearly good character.

Both philosophy and religion have pondered these paradoxes of fortune, and Court has elected to tackle parts of Oedipus’ family story from each angle. Director Charles Newell’s idea is to honor both the University of Chicago’s emphasis on ancient classics that shaped Western thought and the culture of the neighborhood in which the school is embedded; Chicago’s African American South Side is largely a product of the post-Civil War Great Migration.

Thus the first and third Sophocles plays are to be done in the potent and casually direct translations of Nicholas Rudall (1940-1918), esteemed founder of Court Theatre and renowned University of Chicago expert on Sophocles’ era. The second play will be presented as a musical adaption in May 2020 — Lee Breuer and Bob Telson’s 1983 “The Gospel at Colonus,” which tells the story of disgraced and blinded Oedipus through the lens of a Pentecostal vision of heaven as the promised end to earthly affliction.

If in Sophocles’ telling, condemned Oedipus finds a way to accommodate himself to his fate, the African American adaptation of this middle chapter depicts his escape from life as a glorious hallelujah. (See a video of the Broadway number, “Lift Him Up,” from the ’80s, below this story.) Roston will return as Oedipus in this second installment. And Kane, as Oedipus’ brother-in-law Creon, who inherits the throne, will be in the cycle throughout.

The sleek production, suggestive of both ancient time and timelessness, is designed by John Culbert, with costumes of Jacqueline Firkins, and lighting by Keith Parham.

“Oedipus Rex” sets the tone for all that is to come with a sleek, multi-level set (by John Culbert) that radiates spiritual, even seismic, energy. The floor has a grand rift in it. The overall effect is austere, with high steps at the back and shiny surfaces that are responsive to light (by Keith Parham) of almost dazzling brilliance. This place could be a dais, a castle with a moat, a harsh cell, a modern sanctuary. The supporting actors roam dance-like throughout the stage and audience areas, watching and waiting. Jacqueline Firkins‘ costumes are mostly white and flowing, except for Oedipus in royal purple and Jocasta in gold. The sounds designed by Andre Pluess and Christopher LaPorte evoke an eerie sense of time unhinged.

As Oedipus, Roston inhabits the extremes of a hero’s experience. At first this Oedipus comes across as a rather simply drawn, ambitious leader who knows nothing of failure. But in sharpening detail, Roston draws his portrait of an increasingly anxious ruler confronted by successive indications of a culpability so unbelievable and offensive that he will put out his own eyes over it.

And the gods, of course, are not yet done. After Oedipus’ exile in Colonus, a third Sophocles play, “Antigone,” scheduled for autumn 2020, tracks the curse into the next generation.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

- Nicholas Rudall, 1940-2018: Remembered at UChicago.edu

Tags: Court Theatre, Jr., Kelfin Roston, Oedipus Rex, Sophocles