Two stars of CSO see great fun in challenge of Brahms’ towering concerto for violin, cello

Violinist Stephanie Jeong and cellist Kenneth Olsen will play Brahms’ Double Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in performances Nov. 7-12 at Orchestra Hall.

Interview: Violinist Stephanie Jeong and cellist Kenneth Olsen relish chance to play the big work with their friends under Riccardo Muti.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

The two soloists who tackle Brahms’ Concerto for Violin and Cello with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in performances Nov. 7-12, under the baton of music director Riccardo Muti, will be very familiar faces to regulars at Orchestra Hall – Stephanie Jeong, the CSO’s associate concertmaster, and Kenneth Olsen, the assistant principal cello.

While the assignment bestowed by Muti speaks volumes about his confidence in these two key players, and they talk about the opportunity as some really hard fun, the fact remains that Brahms’ Double Concerto is a technical behemoth for both soloists, a work as thorny as it is unusual and one that demands poetry in the mix with virtuosity.

Brahms’ four symphonies, his two piano concertos and the violin concerto all were behind him when he composed the Double Concerto, his last big work for orchestra, in 1887. He conceived of the work as an olive branch for his old friend and close musical colleague, the violinist Joseph Joachim. They had fallen out over the circumstances of Joachim’s divorce.

“At first glance, the piece comes off as technically layered and difficult,” says Jeong, “but when you understand its history as an offering to Joachim, you begin to hear that throughout the piece. It sounds like a conversation between two people, whether they’re arguing or having a playful time. It’s really fun.”

But the Double Concerto hasn’t always struck performers or critics as exactly a fun piece. The work can present a severe aspect that even such astute early listeners as Brahms’ dear friend Clara Schumann found uncharacteristic for so lyrical a composer. And though time has raised the work to a place among Brahms’ masterpieces, and recordings are plentiful, it’s still not played all that often in concert – largely because of the difficulty of bringing together two formidable soloists.

“Brahms makes the cello do everything the violin is doing,” says Olsen with a laugh. “Stephanie has some incredibly hard passages that she plays really fast, and it’s really challenging to get around the length of my instrument as quickly as she can do on the violin.” As Olsen observes, however: “The piece starts with a big passage for solo cello, which is pretty cool.”

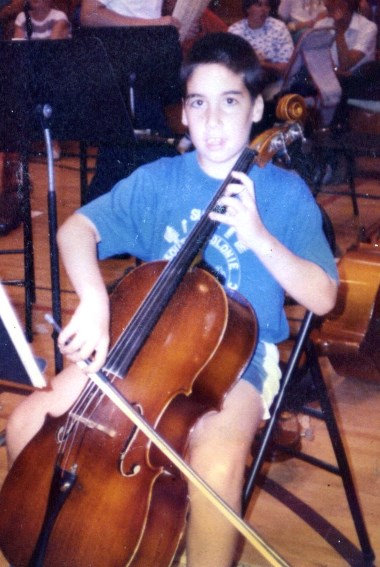

Olsen, a native of New York who studied at the Cleveland Institute of Music and the Juilliard School, joined the CSO as assistant principal cello in 2005. While neither he nor Jeong has ever played the Brahms Double Concerto in a professional setting, they took solo roles in Beethoven’s Triple Concerto with pianist Jonathan Biss, also under Muti’s direction, in 2015.

But even beyond that experience together, says Jeong, “we’re a pretty natural fit. Our playing and our ideas are similar. That’s really important in the Brahms Double because it has a chamber music factor. Very often, I’m accompanying Ken or he’s accompanying me, or we might be playing the melody together. Sometime it’s just us, without the orchestra.”

The spiritual confluence of violin and cello reaches its deepest level in a slow movement that’s framed by the grand and dramatic opening movement and the finale’s wild dance.

“The middle movement is the heart of the piece, it’s so beautiful,” said Olsen. “Stephanie is playing this gorgeous melody, and I keep interrupting in angry bursts.” (“I keep trying to persuade him,” Jeong says, and they both laugh.) “I finally give in,” Olsen concludes, “and we go on together.”

That lyrical middle chapter, says Jeong, poses a particular challenge that has more to do with mindset than technical agility: “It presents such a vast change in character from the opening movement. I think this is where Brahms is reaching out to Joachim.”

Jeong grew up in Chicago and made her solo debut with the CSO at age 12 as winner of the orchestra’s Feinberg Competition. She then went on to study at the Curtis Institute and Juilliard. She was one of Muti’s first appointments to the orchestra when she joined the CSO as associate concertmaster in 2011.

The two musicians’ latest concerto date with the CSO reflects Muti’s wish to turn the spotlight on the orchestra’s stellar group of assistant principals. How these two landed the Double Concerto is a somewhat convoluted story, but the essence of it is that a few years back Olsen let it be known that he’d like to take on this monumental work.

“Later, at an airport when we were on tour,” Olsen recalls, “Muti walks over to me and says, ‘So you want to play the Brahms?’ Just like that. I said sure. And here we are.”

After immersing themselves in the music separately, over the summer, Jeong and Olsen finally got together in early October to begin the melding process of playing a virtuoso concerto for two. Jeong admits that plunging into their first actual collaboration on the piece was her most stressful moment in the whole adventure.

“I didn’t really know how it would go, how the way I had approached the music would match with Ken’s,” she said. “When I saw that all the work I’d done actually fit with Ken’s idea of the piece, that was a big relief.”

One might suppose that stepping to center stage, in front of a hundred orchestral colleagues, would only raise the pressure. Not at all, replies Jeong.

“These are our friends, and they all want to see us have a big success,” she says. “It’s very reassuring to know the orchestra is right there” – she punches a fist into the air – “for us.”

Related Link:

- Performance and ticket info: Details at CSO.org