Pianist Kirill Gerstein, launching Beethoven sonata cycle, sees works as mirror of struggle

Kirill Gerstein will play works from Beethoven’s early and middle periods in the first program of a season-long traversal of the 32 sonatas at Orchestra Hall.

Interview: First of seven eminent pianists who will traverse the 32 sonatas, other major works at Orchestra Hall starting Oct. 13.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

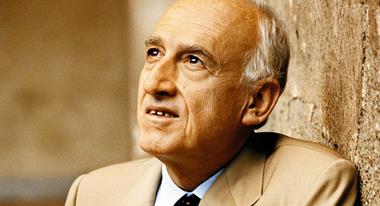

Pianist Kirill Gerstein, who leads off a season-long excursion through Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas to be performed by a parade of virtuosos at Orchestra Hall, views the sonatas not only as the composer’s most personal medium but also as an inventive progression sometimes skewed in modern reckoning – and sometimes unduly sanctified.

Like the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s cycle through Beethoven’s nine symphonies, which will continue throughout the season under the baton of music director Riccardo Muti, the sonata series under the aegis of Symphony Center Presents pays tribute to the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth in 1770.

Pianist Kirill Gerstein on Beethoven: “The sonatas are an accurate reflection of a genius living and aging.”

After Gerstein’s opening recital Oct. 13, the stellar pianists lined up to play Beethoven sonatas continue with Rudolf Buchbinder (who will play two programs), Andras Schiff (two programs), Evgeny Kissin, Igor Levit and Maurizio Pollini. In addition, pianist Mitsuko Uchida will pair Beethoven’s prodigious “Diabelli” Variations with the Six Bagatelles, Op. 126, from his so-called late period.

That charged word “late,” in Beethoven cosmology, especially when it refers to the piano sonatas or the string quartets, tends to elicit something like cosmic reverence. But almost at the top of our conversation, Gerstein debunked both traditional profiling of the early sonatas as all about charm and wit and veneration of the late sonatas for their cosmic mystery.

“The last ones are of course ethereal,” he said, “but there’s a risk in taking too pious an approach to them. The late sonatas are full of gags, sarcasm, humor. Let us not send them too much into outer space. The early and middle sonatas, with all their brilliance, have profound moments, too.”

As Beethoven was a pianist, Gerstein said, the piano sonatas became his most personal form of creative expression. If those 32 essays don’t exactly define an arc of the composer’s evolving art, he said, they do provide dots that afford real insight in Beethoven’s larger musical thought process.

“Through each period, each step of his creativity, we find in the sonatas the precursor of what will happen in the symphonies,” Gerstein said. “The chance to commune with Beethoven’s music through the sonatas is uniquely rewarding in that the revelatory moments continue to come.”

As the launch pianist for the Symphony Center Presents sonata cycle, Gerstein will play five works ranging from the very early Sonata No. 2 in A, Op. 2, No. 2, and Sonata No. 4 in E-flat, Op. 7. The latest work on his program is the middle-period Sonata No. 22 in F, Op. 54.

“The sonatas are an accurate reflection of a genius living and aging,” Gerstein said. “Are changing features of the sonatas the result of Beethoven becoming mature and aging? Is aging better? You do get better at certain things, but in some respects you also stay the same. This is a key philosophical question of the human condition. Yes, we transform over time and can do things we weren’t able to do before – but we also become more static, more problematic. All this is quite palpable in the Beethoven sonatas. We hear that humanity in his music, and we are touched by it. We can all relate to it.

“What I perhaps half-consciously have felt is the value of coming to the solo piano music from Beethoven’s chamber music. Some seasons back, over the course of three years, I played all of Beethoven’s piano music with other instruments – the sonatas with violin and piano, the concertos, which are really large chamber works. So much of his writing for the keyboard alludes to string playing or wind breathing.”

In a sense, says Gerstein, the evolutionary course of Beethoven’s piano sonatas is one of constantly grappling with the idea of the classical sonata – pushing and pulling already time-honored templates to make those prescriptions conform to his own creative instincts.

“Over the 32 sonatas, he works through several models of how to write a slow movement,” the pianist said. “And he relentlessly experiments with the finale: How the hell do we finish this thing? How does the last movement affect overall balance? In the end, with Op. 111, he solves the problem by reducing the sonata to a dichotomy, just two movements. Liszt, who is still underestimated as Beethoven’s inheritor, takes the next logical step, constructing his Sonata in B minor in a single movement with all the features of the Classical four-movement form.”

Even apart from the revered late sonatas, certain works have won and sustained cherished status: the “Moonlight,” “Pathétique,” “Waldstein,” “Appassionata.” Gerstein says the great popularity of those sonatas doesn’t necessarily reflect their relative merit.

“Why did this one or that one get so famous, while the early ones especially are underestimated?” he said. “Even the first sonata is a fantastic piece. And so is the fourth sonata, Op. 7, the longest, by the way, before the ‘Hammerklavier’ (Op. 106). For whatever reasons, the popularity of the sonatas has tended to congeal around Beethoven’s fist-shaking middle period. But they are all treasures to behold. All contribute to the portrait of the incredibly rich creative spirit that Beethoven was.”

The very experience of listening to any music of Beethoven is a singular communal act, says Gerstein, fundamentally different from, say, an encounter with so fluent a genius as Mozart or Schubert.

“We are conscious of Beethoven’s struggle, and we are touched by that,” he said. “It’s harder to identify with Mozart, whose music is so effortless, like Schubert’s. It’s as if those geniuses just turned on the faucet and the music poured out. That was never the case with Beethoven. His music was earned and won. You sense its bruises and its arrogance, its bipolar swings from despair to victory.

“As Brahms said, nobody ever knocked harder on the door of inspiration than Beethoven.”

Related Link:

- Performance and ticket info for the complete cycle of Beethoven piano sonatas: Details at CSO.org

1 Pingbacks »