‘King Hedley II’ at Court: Peripheral Wilson propelled to center stage with bruising force

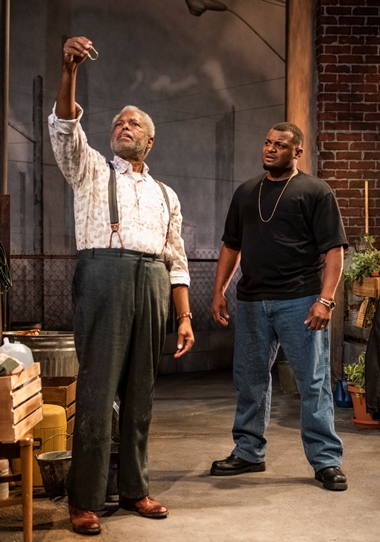

King Hedley II (Kelvin Roston, Jr., left) and his pal Mister (Ronald L. Conner) hope to pool enough money to open a video store. (Michael Brosilow photos)

Review: “King Hedley II” by August Wilson. At Court Theatre through Oct. 13. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Of the 10 plays that make up August Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle, a decade by decade series of tableaux depicting the African American experience through the 20th century, “King Hedley II” may be the least familiar to theater audiences. But this grim, ultimately crushing drama is by no means the least potent. Witness Court Theatre’s knock-out production featuring a stellar cast under the wise direction of Ron OJ Parson.

King Hedley II – or Junior – is recently back on the streets after serving time for murder. Now he wants to make something of himself, on his terms, his way. He and his pal Mister are pooling their profits from various shady enterprises in hope of opening a video store. (This is the 1980s, when videocassettes were high-tech.) Their idea of sweetening the pot is to knock over a jewelry store on an idle afternoon.

Tonya (Kierra Bunch) tells King Hedley (Kelvin Roston, Jr.) that she’s pregnant, but has no intention of repeating the horrid experience of motherhood.

Hedley lives in a rough section of a hard world. His girlfriend Tonya, in her mid-thirties, is pregnant; she doesn’t want the child. She had a child, a daughter, half a lifetime ago. That girl went bad. She can’t endure the heartache again. And what if she has a son, a black boy in this white man’s world where black males tend to die young? No thanks.

The man for whom Hedley is named, let’s say his father, has been dead for some time. Now Hedley the younger shares a tenement with a woman called Ruby, in her early sixties, who is maybe his mother. Hedley doesn’t exactly embrace that idea; actually, he just wants her to go away. He seems to resent her, for reasons not entirely clear; but then Hedley spreads resentment around readily and generously. The world has never cut him a break, so what does he owe anyone?

Into this bleak backyard (the evocative work of designer Regina Garcia) walks Elmore, well dressed, self-assured, formidable, a little older than Hedley’s maybe-mother. Elmore is a gambler, a rounder, a good story-teller and a guy whose bad side you don’t want to be on. An old beau of Ruby’s, Elmore has been away for some time (he’s done time, but that’s not the reason for his most recent absence). He’s known a thousand women, but he says he missed Ruby. So he came back, to her.

Those are the ingredients in Wilson’s pot, and director Parson stirs them with a slow, sure hand. Events are headed in just one direction; we can sense that almost from the start. (Everyone in sight has a pistol.) What we don’t know are the trigger points. We learn that young Hedley committed cold blooded murder to redeem his honor: An acquaintance kept calling him Champ, which is not Hedley’s name. And the annoying guy wouldn’t stop. He called him Champ once too often. Pop. A dozen or so times. Hedley just couldn’t make the jury understand.

Elmore had a similar run-in back years ago. It was over a misunderstanding about a $50 stake in a crap game. Guy was sullying Elmore’s name around town. Elmore knew what to do. If nothing else, a man has his pride.

Flint and stone. Elmore and young Hedley. They’re so alike. Willful, unpredictable, dangerous. Kelvin Roston, Jr., is rock hard as a rebel whose only cause is himself. He bleeds within from the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Roston shows us a man deeply wounded, almost broken, plunging madly down a path toward self-destruction. He slashes away all obstacles before him, impetuously, doggedly; how ironic that he actually wields a machete.

God, the fervent Stool Pigeon (Dexter Zollicoffer) explains to Hedley (Kelvin Roston, Jr.), has already written out everybody’s story.

His splendid foil, his smoldering interlocutor, is A.C. Smith’s Elmore, a grand and worldly figure, committed to his own path wherever that might lead him. Smith’s husky voice and eloquent large body lend irresistible charm to Elmore’s tales of events recent or long past, beguiling or fearful. At heart, Smith’s self-possessed Elmore is who Roston’s cock-sure Hedley might one day become.

If Wilson’s plays typically bear a modern seal of Shakespearean truth, majesty and pathos, “King Hedley II” also reflects the classic essence of Greek tragedy, its damned houses and endless retribution. It is a big play, its language ample and rich, with rigorous, charged monologues for both women (Kierra Bunch as Tonya and TayLar as Ruby) as well as for Elmore. And Ronald L. Conner as Mister, Hedley’s usually exasperated sidekick, provides a sort of weird normalcy in contrast to Hedley’s obsessive drive. Director Parson allows the actors the time and space to let their speeches resonate. It’s powerful, marvelous theater.

I have left for last, as he has the last word, Wilson’s counterpart to the Shakespearean fool. Most of Wilson’s plays offer such an improbably wise, even transcendent voice. Here it is Stool Pigeon, an old man who likes to quote Old Testament admonitions of hellfire and God’s requirements of praise and obedience – or else.

Dexter Zollicoffer is a sweetly genuine Stool Pigeon, though his highest compliment to God surely would be, by the reckoning of most believers, appalling blasphemy. It is an epithet shorn of all excess, absolute and unequivocal. This story we’re watching unfold, Stool Pigeon reminds us, has been all written out by God, the beginning, the middle and the end. You don’t question God. You don’t mess with God. Because God is a, well… One rather imagines God smiling at such clear-sighted deference and replying: “Yes, I am.”

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com