‘The Glass Menagerie’ at the Shaw Festival: In a broken world, illusion collides with reality

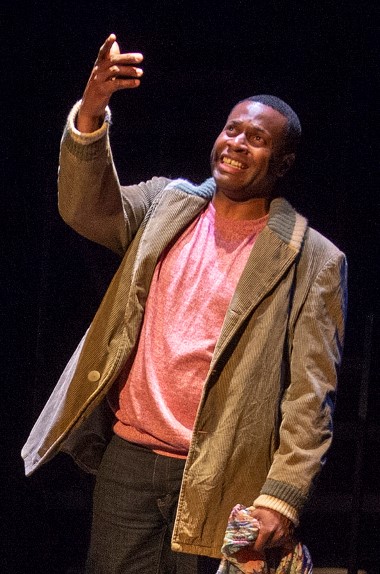

André Sills, who plays Tom Wingfield, first appears performing magic tricks for the audience, illusions before more illusions. (David Cooper photos)

Review: “The Glass Menagerie” by Tennessee Williams, at the Shaw Festival through Oct. 12. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

NIAGARA-ON-THE-LAKE, Ontario – Before the scripted play begins in the Shaw Festival’s searing production of Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie,” the actor who will play the trapped, desperately yearning Tom Wingfield performs magic tricks for the audience.

Wearing a knitted cap, he looks like a street person. Maybe we aren’t looking at a prelude at all; perhaps this is the epilogue – the fate of an aspiring poet who ultimately flees from his dead-end life as sole provider for his domineering, erstwhile Southern belle of a mother and his crippled, withdrawn, psychologically damaged sister.

Illusion may indeed be Tom Wingfield’s final reality. Like mother, like son. For his mother Amanda, long ago abandoned by her husband, living in near penury, clinging to her salad days when her parlor was filled with gentleman callers, illusion functions as a workable version of reality. As for the sister Laura, the play is named for her retreat from the awfulness of life. She collects small glass animals. She is their keeper; they are her world.

But who is “The Glass Menagerie” really about? We have only to follow our ears to answer that question unequivocally: When Allegra Fulton’s fearsome, fearful, tyrannical and bereft Amanda speaks, we know. We surely empathize with Tom’s breathless urgency to get out, to spread his wings, to have a chance, to breathe – and André Sills delivers a potent image of this poet in chains, this Prometheus bound. But it is Fulton’s carping, posturing, ever smiling but irreparably broken Amanda, a true Christian martyr in her own mind, who commands the imagination and shapes the play.

Fulton’s performance is beautiful in its very sadness. Her Amanda is at once a holy terror, doggedly riding Tom from dawn – “Rise and shine!” – to dusk, and a woman nearly mad with worry over their financial plight and the need to find for Laura either gainful employment or a suitable husband. In Fulton’s grand, badgering Amanda, apparently a beauty in her youth who could have had her pick of the gentleman callers but chose badly, we observe the hollowed form of a woman all but beyond options or hope.

As psychological sparring partners, Fulton and Sills are well matched. Her worried, manic Amanda senses Tom slipping from her grip; Sills paints a volatile portrait of the aspiring artist as a young man locked into the mundane requirements of keeping food on the table and the lights on. Increasingly, as she nudges him, he pushes back. She excoriates him for wasting time at the movies – or wherever it is he goes at night just to be out of that stifling apartment; he throws her ceaseless needling – as well as her empty cheerful prattle – back in her face.

Like warring wolves, Fulton and Sills circle each other, fire in their eyes and claws out. They cannot escape each other, even when they seem momentarily to do so. Director László Bérczes has come up with the perfect visual metaphor for the mutual entrapment of mother and son: a square walkway around the apartment set, over which the audience looks from all four sides. Walk or run as they might, they only end up back where they started. Flight is just one more illusion.

The breaking point comes when Tom honestly tries to satisfy Amanda’s incessant request that he bring home some nice young man to dinner, to meet Laura: a gentleman caller who might be charmed by Laura’s better qualities and maybe even marry the girl.

Tom works at a shoe company, where he writes poems on the lids of shoe boxes. He has acquired the nickname Shakespeare. He invites a co-worker (Jonathan Tan) to dinner, an occasion for which Amanda spends every possible penny in preparation. On the big night, Laura (the sympathetically understated Julia Course) opens up enough to share her glass menagerie with her gentleman caller.

In a lovely touch, Course’s impressionable Laura forgets herself and her lame foot in a whirling dance with her empathic guest. But when this particular illusion – a white knight for Laura – blows up, the furious Amanda blames Tom, as if he had played a mean-spirited trick on both her and Laura.

It’s the last straw. Tom, narrator of this remembered mash-up of illusion and reality, breaks out once and for all. But that’s where we came in, with the illusionist, the guy in the knit cap – the poet manqué.

Related Link:

- Shaw Festival’s complete summer season: Read it here