‘Moby-Dick’ at Chicago Opera Theater: Condensing the scope, cranking up the power

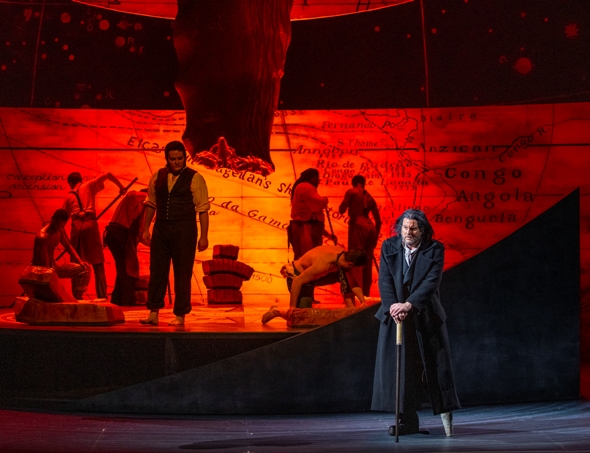

A new production brings the grand opera “Moby-Dick” within range for smaller stages. In an early scene, Captain Ahab offers to make the man rich who spots his white whale and nemesis, Moby-Dick. (Photos by Michael Brosilow)

Review: “Moby-Dick” by Jake Heggie and Gene Scheer, produced by Chicago Opera Theater at the Harris Theater. ★★★★

By Nancy Malitz

I saw Jake Heggies’ opera “Moby-Dick” at its world premiere in Dallas in 2010, when it marked the unveiling of the dazzling new Winspear Opera House in the city’s downtown arts district. “Moby-Dick” was a grand opera production with the emphasis on grand: cutting edge technically for its time, with enormous set pieces, elements flying in and out from above, lighting sufficient to evoke boat-swallowing storms at sea, and whale-size computer graphics. The heroically voiced Wagnerian tenor Ben Heppner created the role of Herman Melville’s obsessed ship captain Ahab, who loses his mind and sacrifices his crew in a revenge run against the almighty beast that maimed him.

Everything about that Dallas premiere was gargantuan, and new. Surprisingly, a nifty mid-size design concept, presented over the April 25 weekend by Chicago Opera Theater at the Harris atop Millennium Park, was just as thrilling, in some ways even more intense, as it zoomed in on the swirling human action aboard the whale-hunter ship, its subjugated sailors and the lurking danger in the vast surround.

What a gift to Chicago’s audience, to be able to experience the true essence of this “Moby-Dick” by the midwestern American composer Jake Heggie, 58, who first emerged at the turn of the 21st century at the dawn of a new American opera boom. These days, I hear new opera everywhere, though it comes mostly from the operatic equivalent of off-Broadway – from the smaller, often younger companies, paid for with modest entrepreneurial wherewithal and aimed at different mountaintops by composers younger than Heggie by decades. Heggie stands somewhat apart for his mainline connection to the American cultural renaissance that Melville, Hawthorne and Whitman personified. They were very democratic in spirit and not at all self-conscious about language that celebrated emerging American themes and sensibilities even if they reflected European forms and influence

“Moby-Dick” is composed in an essentially tonal, acoustical style for the traditional orchestra and the operatic voice, yet it speaks directly to our time. It’s hardly an insult to say that if Steven Spielberg needs another movie soundtrack, Heggie might be a guy to ask – or that Heggie’s high-energy sailors choruses put one mind of the rambunctious Seabees in “South Pacific.” Yet Heggie’s a grand-opera man. His music has a marvelous elasticity to it that is as expansive as Richard Strauss, with that tendency to stretch the line to a tenuous thread just short of breaking. “Moby-Dick” also shares a sense of naturalism with mid-20th-century works like Britten’s “Peter Grimes,” which speaks so powerfully about the sea, storms, sunrise, and the destructive hurricane of personal madness that rages within.

Chicago Opera Theater music director Lidiya Yankovskaya led a first-class cast starring tenor Richard Cox (mercilously authentic on his peg-leg contraption as the vengeful Ahab), a 60-piece orchestra, and an agile 38-member chorus in the service of this demanding opera. “Moby-Dick” doesn’t sound Italian at all, but it loves singers the way Verdi operas do, and Yankovskaya conveyed its Verdi-like sense of tension and forward motion, knowing where to dwell and reflect, how long to cower, when to pounce, how to switch gears and get on with it.

Heggie’s critically important collaborators were Terrence McNally, who had the original idea, and Gene Scheer, who wrote the libretto. The current production is directed by Kristine McIntyre, spectacularly lit by David Martin Jacques, and smartly conceived by scenic designer Erhard Rom for seamless transitions on smaller stages. It was constructed in Salt Lake City to fit the requirements of the Utah Opera, Chicago Opera Theater and other participating partners in Pittsburgh and San Jose, with future dates in Barcelona and, almost certainly, a life beyond.

Thus “Moby-Dick” is a nifty remake, with a revolving unit set that represents the luckless whaling vessel Pequod. It can be quickly maneuvered from all angles, as if on water, by a crew of trained dancers with some fairly awesome rope and harpoon moves that serve as metaphor for the impossibly fast, athletic and deadly job of reeling in a surging whale at sea. The hyper-active story-telling incorporated an element of sophisticated dance movement that has long been a norm of the American musical, and it also harkened back to the spectacular 2017 Lyric Opera production of Gluck’s “Orphée et Eurydice,” directed by John Neumeier, which made ballet central in the story-telling.

Perhaps the most physically demanding role in “Moby-Dick” is not for a dancer at all, but for the Ahab who must range about the stage on a fake peg-leg that compromises movement. Heldentenor types tend to be big guys, but Richard Cox, who did Ahab duty recently in San Jose, is also of the athletic sort, and he had the hobbling drill mastered. Cox is an intelligent musician, with a beautiful vocal instrument, who came across not so much as a malevolent monster as a blindered, bellowing man, oblivious as he destroys his ship and crew.

Baritone Aleksey Bogdanov was excellent as Starbuck, the first mate with a conscience. He was a good guy in this opera; but one senses Bogdanov would make a fine villain Scarpia, too. In a strong cast, bass-bartione Vince Wallace, tenor Andrew Bidlack and soprano Summer Hassan were notably charming as Queequeg, the harpooner with strange native ways; Greenhorn, the young man tutored by Queequeg; and Pip, the piper-voiced cabin boy who drowns. Complementing the excellent chorus were simple projections that mimicked the undulating ocean waves and infinitely vast night sky. I found this “Moby-Dick” to be quite convincing.

Except for one thing. The great white whale’s pop-up hello near the end of the show was a letdown, let’s be frank. But then Spielberg’s shark in “Jaws” was pretty tacky, too.

1 Pingbacks »