Striking CSO musicians to give free concerts; Barenboim, Pelosi send messages of support

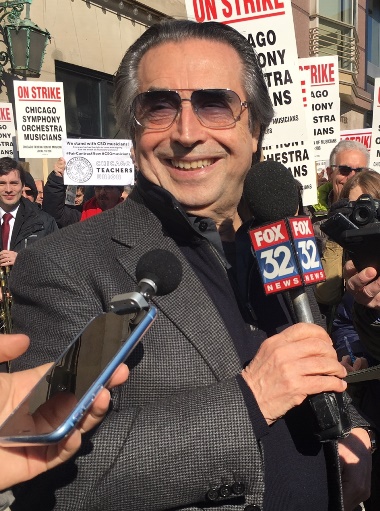

Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Riccardo Muti joined the striking musicians outside Orchestra Hall on March 12. (Nancy Malitz photo)

Updated Report: Stuck at impasse after weekend talks, Chicago Symphony musicians and management agree on a timeout.

By Nancy Malitz and Lawrence B. Johnson

Updated March 20: The striking musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra will give two free performances they have dubbed “From the Heart of the Orchestra – Free Concerts for Chicago.” The two programs, announced as the first events in a projected series of free presentations, will feature a small ensemble playing chamber music March 22 and the full orchestra in works by Beethoven and Mozart on March 25.

The musicians also made public letters of support from former CSO music director Daniel Barenboim and Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Daniel Barenboim, former music director of the CSO, sent a supporting letter to the striking musicians. (Rudy Amisamo de Lespin, Staatskapelle Berlin)

Characterizing the orchestra as “a cultural jewel of the world” in a statement, Barenboim said, “I would like to encourage

the board, the musicians, the public and the city of Chicago to resist any attempt that will reduce such status. I offer my full support to the musicians of the CSO.”

Pelosi’s letter read, in part: “Democrats stand in solidarity with you in asking the Chicago Symphony to come to the table with respect for the value of your work.”

The March 22 chamber music program, including works by Mendelssohn and Vivaldi among others, will begin at 8 p.m.

at the PianoForte Studios, 1335 S. Michigan Ave, 2nd Floor. To obtain the free tickets, available on a first-come, first-served basis, go here. The full orchestra concert, at 7:30 p.m. March 25 at the Chicago Teachers Union Hall, 1901 West Carroll Avenue, offers Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony and Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto with CSO principal clarinet Stephen Williamson as soloist. CSO trombonist Jay Friedman will conduct. To obtain free tickets on the same basis, go here.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association has canceled all CSOA-presented concerts scheduled to take place at Symphony Center from Wednesday, March 20, to Monday, March 25. CSOA said it has canceled the concerts due to the ongoing strike by musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. After negotiations March 15-16 failed to produce an agreement, the two sides decided to take a break with no further talks planned.

CSOA-presented concerts to be canceled include:

- Symphony Center Presents Special Concert featuring George Hinchliffe’s Ukulele Orchestra of

Great Britain on Wednesday, March 20. - CSO subscription concerts on Thursday, March 21, and Saturday, March 23. The program, which was to have been led by guest conductor Osmo Vänskä, featured Sibelius’ “Night Ride and Sunrise,” Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 (“Scottish”) and Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 with Vadim Gluzman as soloist.

- CSO movie presentations of “An American in Paris” on Friday, March 22, and Sunday, March 24.

- The public and school performances of “Once Upon a Symphony: The Boy and the Violin, A Brazilian Folktale,” on Saturday, March 23 and Monday, March 25.

- Civic Chamber Music concert at the National Museum of Mexican Art on Saturday, March 23, at 2:00 p.m.

- All associated pre-concert special events through March 25 are also canceled. Announcements of cancellations for additional concerts and events that may be affected by the strike will be issued if necessary.

The striking musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra heard on-the-street pledges of support this week from music director Riccardo Muti and Toni Preckwinkle, president of the Cook Count Board. Preckwinkle, a candidate for mayor, joined the picketing musicians in the rain outside Orchestra Hall on March 14, as Muti had done in balmy sunshine two days earlier, to proclaim her alignment with them in no uncertain terms.

Cook County Board president Toni Preckwinkle braved the rain March 14 to lend her supporting voice to the musicians.

“I think it’s insulting that billionaires should say to ordinary working people – in this case musicians – that they have enough,” Preckwinkle said. “I think it’s really important that we support working people in our city and surely our musicians are working people. I’m here to strongly support our musicians and the good work they do, the ways in which they enrich our lives.”

Muti, in town to lead in his orchestra in now-canceled concerts March 14-16, broke with the convention of music directors staying out of musicians’ contract negotiations to affirm his unity with the striking players.

Insisting that he was “not against” the Board of Trustees of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association, Muti said: “I just would like that they understand and listen more carefully to the needs of musicians, who represent one of the greatest orchestras in the world. The entire world is listening to what is happening in Chicago. The Chicago Symphony goes around the world. The musicians not only play, they are the ambassadors of the culture of this country. It is a big responsibility for the city of Chicago (and) for the board to take care of this treasure. This is a moment of crisis, but I am sure with intelligence and good will, this will be solved.”

If Muti tone was conciliatory, the tenor of the picketing musicians was angry, especially on the central bone of contention over the board’s proposal to restructure the musicians’ pension plan, shifting the investment risk to the individual players.

“It is reprehensible that they should even mention that,” said clarinetist John Bruce Yeh. “It’s a bad deal for musicians when they are taking away something (the so-called defined benefit pension) that we have had, have worked for, for 50 years, It’s an insult.”

The board has declared the current pension structure, which by federal rule has required substantial increases in CSOA contributions in recent years, to be unsustainable.

“I think there was some inattention to the pension over years,” said Stephen Lester, a bassist in the orchestra and chairman of the musicians’ negotiating team. “In the ’90s they didn’t have to put a lot of money into the pension because the investment fund was doing so well. But then the investment management changed, and the investment went south, and so built up this enormous accumulation of liability which now is a substantial number. But that is nothing that is the result of musician activity. A pension is a promise, a promise we all have had as a central reason why we have committed to the city of Chicago, committed to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, our entire lives.”

In a press conference-by-phone March 11, the Association reiterated its staunch position on getting out of the pension guarantee business.

The musicians went on strike March 11 after 11 months of negotiations failed to produce a new contract agreement. The “defined benefits” at issue were not on the table when negotiations were concluded three years ago. At that time, modest salary increases of five percent over three years were agreed upon, and the defined pension benefit for retirees was increased from around $75,000 per year to $78,225, depending on starting date, with increments for longer years in employment. This year, the CSO is offering similar salary increases but is demanding a significant pension overhaul.

With some 20 reporters connected to comments from CSOA president Jeff Alexander and Board of Trustees chair Helen Zell, the two officials reaffirmed the Association’s resolve to revise the fundamental structure of funding the musicians’ long-term benefits. Alexander said the cost of the pension fund, about $800,000 two years ago, had soared to $3.5 million this year and would jump again to around $5 million next year because of new federal regulations. Management wants to move the musicians into a defined-contribution plan, similar to a 401(k). The orchestra would put a set amount of money into individual retirement accounts for the players, who could invest it as they chose.The musicians have objected to the plan as high risk.

Appearing in good spirits, Muti said he hoped the CSOA board “would understand and listen more carefully to the needs of musicians, who represent one of the greatest orchestras in the world.” (Malitz)

Alexander noted that although the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, San Francisco Symphony and Chicago Symphony still guarantee a “defined” annual pension benefit through an investment program managed by those institutions, the Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra and Los Angeles Philharmonic have converted their funds into programs that become the responsibility of individual musicians to manage.

Part of the pressure on trustees is that Federal regulations stiffened across the industry when it became apparent that too many of the nation’s pension programs are underfunded. Yet defined benefits remain the gold standard among top orchestras, and players in Chicago have made preserving their benefit a priority.

The two sides also appear to be some distance apart over pay. The Association has offered the musicians incremental raises of 1 percent, 2 percent and 2 percent over the three-year life of its proposed contract, bringing the base pay to $167,000. The musicians have asked for a cumulative three year raise of 12.5 percent, bringing their base pay to $178,000.

The musicians contend that the Association’s salary offer would lower the CSO’s scale to fifth or sixth in the country after having been first as recently as 2014. Effective with the 2015 contract, the CSO’s salary dropped to third. That disparity would compromise the orchestra’s ability to attract the best players. Alexander noted that the cost of living – especially housing – is significantly less costly in Chicago than in cities such as Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

The strike, underscored by picketing outside Orchestra Hall and a request by the musicians union that neither colleagues nor patrons cross the line, has resulted in a suspension of concerts in the near term.

Concerts scheduled March 14-16 under CSO music director Riccardo Muti, featuring CSO flutist and piccolo player Jennifer Gunn in two concertos, have been canceled, along with a performance March 17 at Orchestra Hall by violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter.

Muti spoke with CSO flutist and piccolo player Jennifer Gunn, whom the strike deprived of solo performances with the orchestra. (Malitz)