In remembrance of Italian massacre in WWII, Muti and CSO turn to an American’s lament

Not forgotten: Coffins adorned with fresh flowers at Rome’s Fosse Ardeatine, site of the shooting of 335 Rome civilians by German soldiers in the last days of WWII. (Wiki Commons)

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus memorial concert, Riccardo Muti conducting, at Orchestra Hall.

By Nancy Malitz

As the past recedes, the violence against victims of World War II is in danger of becoming an abstraction. How can it be otherwise when the men and women who survived to tell their ghastly stories – and now even most of the children who were its youngest witnesses – have mostly passed away? Some of them are still tracing their ancestors from helpful resources like genealogy websites. All the more important, then, is to build memorials that can provide sustained enlightenment, deeper consideration, and even, eventually, healing balm.

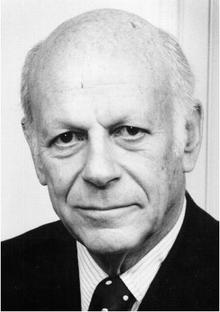

Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Riccardo Muti, who has dedicated several recent concerts to victims of specific terrorist killings in America and around the world, found himself recently drawn to a profoundly affecting symphonic work from 1969 by the American composer William Schuman (1910-1992). His Symphony No. 9 was written in response to a horrifying event in Italy near the end of WWII. (Schuman was central to New York life in the mid-20th century, when he ran both the Juilliard School and then all of Lincoln Center, but his music is only now receiving serious second listens as history, with its retrospective clarifying power, assigns steadily higher valuation to his soaring ideas.)

Composer William Schuman’s visit to Rome’s Ardeatine memorial in 1967 inspired his Ninth Symphony, which Muti and the CSO performed for the first time. (Wiki)

Muti himself was but 27 when Schuman’s Symphony No. 9 (“Le fosse Ardeatine”) was first performed by Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. And the Italian maestro was only 3 years old when the historic events occurred for which the symphony was named: Taken by Nazi soldiers to Rome’s Ardeatine caves, at the city’s outskirts, 335 random Italians were each felled by a single bullet to the back of the head. It was a direct response, dictated by Hitler, for the deaths of 32 German soldiers killed by an improvised bomb planted by Italian partisan fighters along a Roman side street.

The Führer intended to send a message. But it was already March 24, 1944, and the avenging soldiers, knowing that the end of the war was at hand, made a great effort to hide the evidence of their atrocity, covering the bodies with garbage and bombing the entrance. When Rome was liberated June 4, 1944, its citizens rushed to pore over what human bits remained and eventually assembled the evidence in excruciating detail.

The scar that remains is still painfully fresh in Italy, as indicated in the attention given by visiting dignitaries who paid their respects in a presentation at Orchestra Hall. Sergio Mattarrella, president of the Italian Republic, in a letter of appreciation, acknowledged the need “to spare no effort in the preservation of tolerance, and the respect of human dignity and peace.” Armando Varricchio, the Italian ambassador came in from Washington, D.C., to speak. Federico Rampini, the New York-based bureau chief of the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, participated in a public discussion with Anthony Cardoza, professor at Loyola University, whose specialty is modern Italian history. And in the rotunda at Symphony Center, a powerful display of maps, photographs and scraps of clothing from the dead made the distance of 75 years from the harrowing incident seem like yesterday.

Riccardo Muti added Schuman’s Symphony No. 9 (‘Le fosse Ardeatine’) to his repertoire for these commemorative performances. (Todd Rosenberg, CSO)

Were Schuman’s elegiac Symphony No. 9 given no illustrative title at all, the eerie weightlessness of its muted opening phrases – for paired strings barely above the threshold of silence – would have signaled its seriousness of purpose.

As the long, hypnotic melodies began to repeat and overlap, the sound envelope of this reverie floated almost imperceptibly higher, subtly escaping gravity’s pull. (Perhaps because of the Italian who was conducting, Schuman’s still-voiced passages put me in mind of Mascagni’s “Cavalleria rusticana,” with its profoundly ironic orchestral interlude that prefaces the heart-breaking atrocity of a crime of passion in a tight-knit community of villagers on their holiest of days.)

Schuman followed the string opening with the sorts of sounds that might invade a landscape devoid of human life — birdsong-like and insect-like chattering, percussive thumps and whispers, driven by newly syncopated, often jazzy, energies, and capped by an almost Brahmsian, coruscating early peak for soaring horns. Here is music that looks difficult to play on the page, but is in fact easy to hear, potently shaped and clearly European in its roots, but with unmistakable American muscle, anxiety and accent.

The symphony’s middle section unfolded as deceptively playful, its writing for woodwinds, brass and timpani spectacularly delivered by the CSO’s virtuosos. In solos, fleeting pairings, even in what could be described as intricate flock formations, the orchestra wove a busy tapestry of life punctuated by nattering city rhythms and more sharp-edged jazz licks. The whole grew increasingly agitated, suggestive of clamor and conflict, in the buildup to an expansive final section overwhelming in its starkly sighing plaint, persistent percussive rumblings and stridently unresolved, tolling judgment.

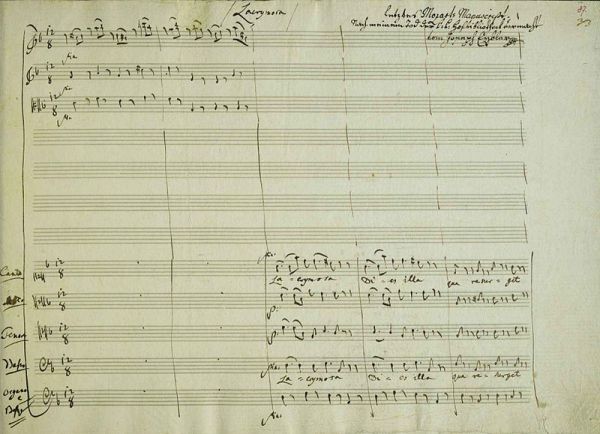

Muti paired the ambitious Schuman with Mozart’s beloved Requiem for chorus, orchestra and a quartet of vocal soloists, which the composer left unfinished at this death at age 35. In fact, Mozart made it only through the opening eight bars of the “Lacrymosa,” the rest completed by his pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr from, it appears, Mozart’s instructions.

Muti maintained a somber spirit throughout, coaxing slower tempos and softer sounds from all forces than are often taken. That, of course, requires enormous discipline and effort, and while there were transfixing stretches, the matinee performance I heard Feb. 22 was not altogether successful. Although the orchestra fared well, the chorus seemed at times stretched to the point of losing control of the intense quiet at its most extreme. (It was the second performance by those singers in less than 24 hours, which may have been a factor.)

The soloists in Mozart’s Requiem, left to right, soprano Benedetta Torre, contralto Sara Mingardo, tenor Saimur Pirgu, bass Mika Kares (Rosenberg, CSO)

The quartet of solo singers was an interesting if somewhat awkward mix of the veteran and the ingenue: The clear soprano of newcomer Benedetta Torre held obvious promise, although her delivery of Mozart’s music sounded tentative. The highly respected veteran Italian contralto Sara Mingardo, ardent Albanian tenor Saimir Pirgu and Finnish bass Mika Kares (a fast-rising newcomer, who in November will make his Lyric Opera debut as the Commendatore in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” ) rounded out the foursome.

Related Links:

- Read Italian journalist Federico Rampini’s account of the Ardeatine massacre: Go to CSO Sounds and Stories