Orozco-Estrada leads CSO through nature’s realm in pageant of Mahler Third Symphony

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada. At Orchestra Hall through Oct. 14.

By Kyle MacMillan

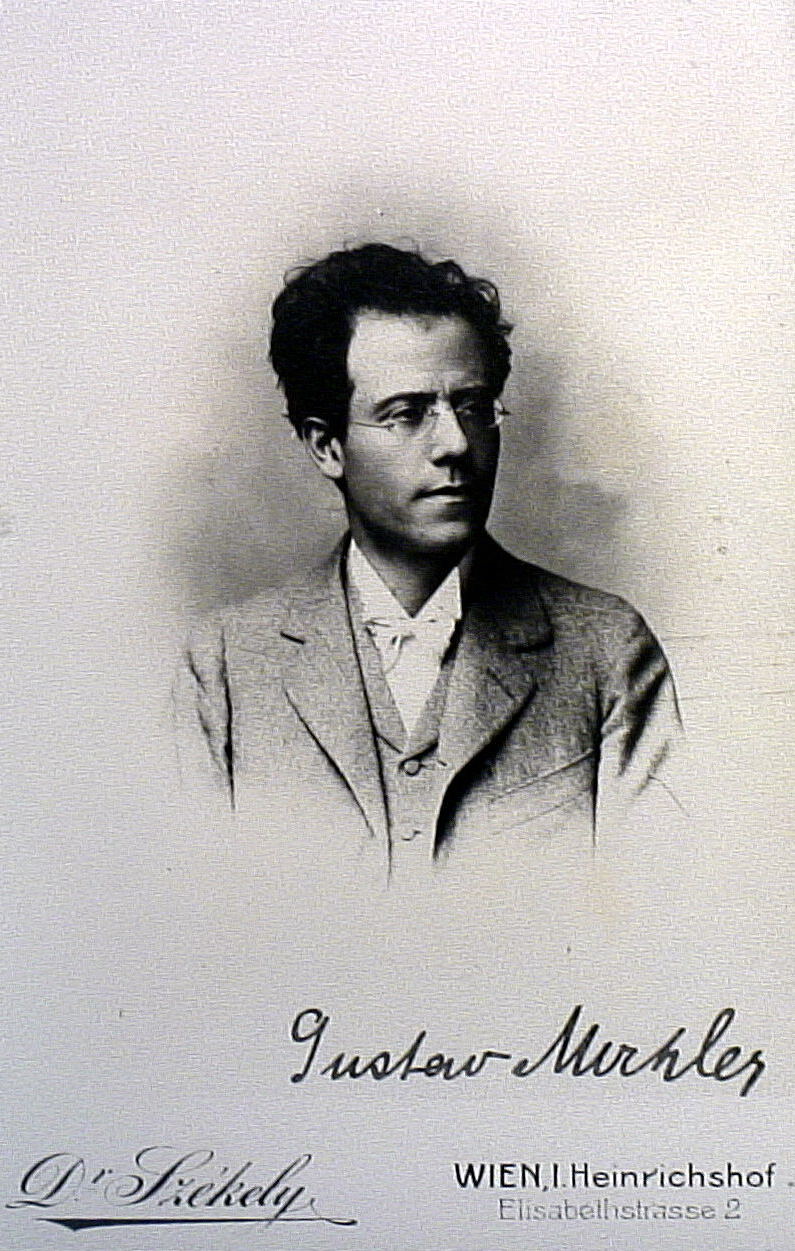

Gustav Mahler once called it “A Summer’s Midday Dream.” But while the sounds of birds chirping and animals flitting can be heard in the Symphony No. 3 in D minor, the work is much more than a mere evocation of an idyll. Indeed, the composer takes listeners on an extraordinary musical, philosophical and auto-biographical journey.

Serving as guide Oct. 11 when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra presented the first in its latest set of performances featuring this landmark work was guest conductor Andrés Orozco-Estrada. The 40-year-old Colombia-born maestro took over as music director of the Houston Symphony and chief conductor of the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra in September 2014.

Chicago Symphony officials placed considerable confidence in this young, emerging conductor by entrusting a work of such magnitude to him, and he delivered a performance that captured the full richness, variety and scope of Mahler’s odyssey and gave voice to the distinctive character of each movement. Clear, purposeful and not oversold – this was a sweeping yet meticulously detailed interpretation.

The Third Symphony is a highly unusual piece in form. Comprising six movements instead of the usual four, it is the longest of Mahler’s works and one of the longest symphonies in the standard repertoire, clocking in at 105 minutes without intermission Thursday evening. Though not involving the massive forces of the composer’s Symphony No. 8 (“Symphony of a Thousand”), it nonetheless calls for an augmented orchestra – nine French horns, for example, were employed Thursday – and women’s and children’s choruses.

Although the bulk of the Third Symphony is instrumental, Mahler introduces vocal writing in the fourth and fifth movements – something he does in several of his symphonies. The Women of the Chicago Symphony Chorus (75 strong) and Anima (formerly the Glen Ellyn Children’s Chorus) took center stage in the ebullient fifth movement, and the two impeccably prepared ensembles acquitted themselves with aplomb.

The solo vocalist is heard briefly in the fifth movement, but her principal contribution comes in the fourth – a setting of the “Midnight Song” from Nietzsche’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” that offers a meditation on joy and pain. Featured here was Kelley O’Connor, who is listed as a mezzo-soprano but is more accurately described as an alto – the vocal type Mahler wanted in this role. Her dusky, full-bodied voice could hardly have been more fitting. O’Connor is highly regarded in the classical world, and this short but critical appearance made clear why.

Mahler calls for a tempo that is “Very Slow. Misterioso,” and that is exactly what O’Connor and Orozco-Estrada delivered. The singer paid close attention to each phrase, each word, minutely shaping her phrasing and subtly adjusting vocal timbres for a spellbinding, time-stopping performance that made this movement one of the clear highlights of the evening. Although singing with a kind of hushed quality, her projection never wavered and every word could be heard.

The other standout movement, labeled “What Love Tells Me” in Mahler’s original program for the symphony, is the sixth movement, with its communion with God and nature. In a letter to soprano Anna von Mildenburg, the composer wrote, “I might equally well have called this movement “What God Tells Me” – in the sense that God, after all, can only be comprehended as Love. And so [the Third Symphony] is a musical poem that progresses through all the stages of evolution … beginning with inanimate Nature and proceeding step by step to God’s love.”

Opening with just strings and building to a kind cathartic apotheosis, this nuanced, beautifully shaped section achieved a true level of transcendence – a fitting culmination to a compelling, evening-long journey.

The first movement – the longest that Mahler wrote and virtually a symphony in itself – is a study in contrasts. The evocation of nature is set against Dionysian revelry and the intervention of Pan, with pastoral moments and delicacy set against others that are ominous and unsettled. Amid the ever-changing, multilayered complexity, outbursts of brass and percussion were offset by sumptuous strings, tittering piccolos and plaintive solos by principal trombonist Jay Friedman, who showed just how expressive that instrument can be. Orozco-Estrada gave voice to all these competing cross-currents, bringing a sense of well-balanced cohesion to the whole and never letting the energy flag.

After a light, airy and intoxicating take on the dance-like second movement, Orozco-Estrada and the orchestra lit up the high-spirited third movement, which Mahler originally titled “What the Animals of the Forest Tell Me.” The carefree joyousness is briefly clouded with the intrusion of humankind, as indicated by the offstage sounds of what the composer intended to be a post horn (a valveless cylindrical brass instrument). Here the masked solos were capably effected on a standard trumpet by assistant principal trumpet Mark Ridenour.

Related Links:

- Performance times and dates: Details at CSO.org