‘Pamplona’ at Goodman: Gray lion Hemingway contemplates life, mischance and le mot juste

“Pamplona” by Jim McGrath, monodrama starring Stacy Keach, at Goodman Theatre through Aug. 19. ★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Ernest Hemingway was, in flesh and blood, a man’s man, the willful and danger-defiant sort we associate with the fantastical, celluloid John Wayne. Recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for literature in 1953 and the Nobel Prize in 1954, Hemingway also shared a trait in common with many another towering artist: For all his exterior magnificence, he was troubled, depressive, vulnerable.

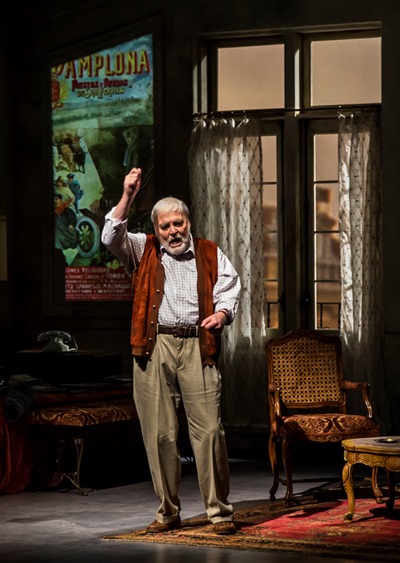

It’s the compleat Hemingway, fierce and brilliant, tormented and alcoholic, that playwright Jim McGrath attempts to sketch and actor Stacy Keach embodies in “Pamplona,” an imperfect portrait of the artist as an aging man, now on display at Goodman Theatre.

Pamplona, the Spanish town famous for its annual running of the bulls, became a favorite retreat for Hemingway. He loved the bull fights, the bold matadors facing down that mass of fury, man and beast taking each other’s measure – and finally the hero, deft and superior, ending it with a fatal thrust.

Pamplona, the Spanish town famous for its annual running of the bulls, became a favorite retreat for Hemingway. He loved the bull fights, the bold matadors facing down that mass of fury, man and beast taking each other’s measure – and finally the hero, deft and superior, ending it with a fatal thrust.

Hemingway must have identified powerfully with such fearlessness. He bore the scars of his own courage. He was severely wounded at age 18 while serving as a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy in World War I. In World War II, he received the Bronze Star for bravery for his coverage of the war. In every way, this native son of Oak Park, Ill., was the rugged individualist.

As “Pamplona” opens, Hemingway is once again holed up in this town he loves, wrangling with a new novel about rival matadors. It is not going well. He’s at a loss for a word, a descriptor: that first gut feeling of the matador in the ring at the point of confronting the bull. From where I sat, there was more bull here than met the eye. I was reminded of the scene in the film “Amadeus” where the composer Antonio Salieri is trying desperately to follow the dictation of the dying Mozart – as if Salieri were some amateur struggling to execute a routine process of aural transcription. It is not a credible scene.

Neither is this one, and it goes on for quite a while: Hemingway, the virtuoso wordsmith, behaving like any ordinary soul who imagines himself a “word person,” unable to come up with le mot juste, crumpling paper, prowling about the room, muttering his frustration. My reaction was, C’mon, man, who’s the challenged writer here? It ain’t Hemingway, but it might be the guy writing about the writer.

Hemingway famously answered the question, How do you become a writer?, with the quip: “It’s easy. Just sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” He wasn’t talking about scratching out one reluctant word at a time, like popping so many sores, but rather of bleeding from the internal wounds of truth. That kind of authentic blood-letting occurs only here and there in “Pamplona,” a good deal of which suffers from either an aura of contrivance or a want of muscle in the language..

This production directed by Robert Falls, Goodman’s artistic director, is a revival of an aborted effort from spring 2017, when Keach became ill on opening night – after 11 preview performances – and the run had to be cancelled. It’s played on a spacious, handsomely detailed set designed by Kevin Depinet, with large-scale projections created by Adam Flemming, notably of Hemingway’s sundry wives and lovers. Keach, now 77, looked and sounded quite fit at the performance I attended. Director and actor apparently agreed to show Hemingway as a lion in the winter of his discontent, mellowed, if not defanged. He growls softly, in remembrance.

Yet there is circumstance here to bite into with real emotional teeth: It’s a few years after the sequence of the Pulitzer and Nobel prizes. The hugely honored artist stands between the mirror (Am I the genius they say I am?) and the abyss (Can I do it again?). I wanted to hear the soul-searching of a man who has ventured far in heart and spirit, and learned about himself. I sought the resonant echo of Hamlet’s profound rhetorical question, What is a man?

Hamlet’s struggle is to avenge his father – “a thought which, quarter’d, hath but one part wisdom and ever three parts coward.” Hemingway’s is to get his head down, to overcome the doubt and fear, and write. But instead of serious reflection, some insight into truth’s agonizing excavation, we get an old man reminiscing on the golden days in Paris with F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein and the sorry history of his four marriages.

What’s best and most worthy of McGrath’s literary subject is Hemingway’s poignant recollection of the woman who got away, the love of his life – Agnes von Kurowsky, the 26-year-old nurse who attended the badly injured 18-year-old in World War I. They fell in love, but she was wary of committing her life to a lad with no clear prospects. So she sent him home to Oak Park to make something of himself while they stayed in touch, which they did regularly – until the day Hemingway got her letter saying she was soon to be married. The pain of that loss rang palpably in Keach’s voice.

What’s best and most worthy of McGrath’s literary subject is Hemingway’s poignant recollection of the woman who got away, the love of his life – Agnes von Kurowsky, the 26-year-old nurse who attended the badly injured 18-year-old in World War I. They fell in love, but she was wary of committing her life to a lad with no clear prospects. So she sent him home to Oak Park to make something of himself while they stayed in touch, which they did regularly – until the day Hemingway got her letter saying she was soon to be married. The pain of that loss rang palpably in Keach’s voice.

There’s an adage in theater that if you see a gun in the first act, it will come into play in the second. Keach’s Hemingway muses on – and briefly brandishes – a gun handed down to him by his father. Seems his father had taken it from Hemingway’s grandfather after the latter threatened to use it on himself. But in the end, it was Hemingway’s father who shot himself. Here, it’s just an object, a keepsake. But there is a real-life epilogue.

Not long after the timeframe of this play, the celebrated novelist would again find himself in that familiar daunting place between mirror and abyss. And in that instance, in 1961 just shy of his 62nd birthday, he would make his own answer to another of Hamlet’s rhetorical questions: to be, or not.

Hemingway once observed: “There is nothing noble in being superior to your fellow man; true nobility is being superior to your former self.” Such is the pith and grace of language too little found in this approximation of a true writer.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Go to TheatreInChicago.com

Tags: Ernest Hemingway, Goodman Theatre, Jim McGrath, Pamplona, Stacy Keach