Like a constellation viewed above the skyline, Grant Park Chorus ascends in Chicago night

Review: World premiere of “The Pleiades,” by Latvian composer Ēriks Ešenvalds, at the Grant Park Music Festival, Carlos Kalmar conducting, June 20. (The free concert repeats Friday, June 22.)

By Nancy Malitz

For the second week in a row, Chicago has hosted an assemblage of special ears – first, a thousand representatives of the nation’s orchestras large and small June 12-15, followed hard upon by their mighty choral counterparts. They arrived June 20 and remain into the weekend to celebrate singers, and song, and the brain on music, while sharing ideas and hobnobbing with the best practitioners in the field.

To entertain these golden throats, the Grant Park Festival Orchestra and Chorus put on a veritable smorgasbord of choral-orchestral delights June 20 at Millennium Park. The headliner was a world premiere of “The Pleiades” by the Latvian composer Ēriks Ešenvalds. It played nicely in the out-of-doors in preamble to starlight and fireworks as the summer solstice drew near.

(Rossini’s “Stabat Mater,” by the Chicago Symphony Chorus and Orchestra led by Riccardo Muti, along with a veritable galaxy of additional concerts from the Chicago Children’s Choir, the St. Charles Singers, Schola Antiqua, and many other ensembles are also scheduled around town this week. So if you think you hear singing, this time you can assume it’s not just in your head.)

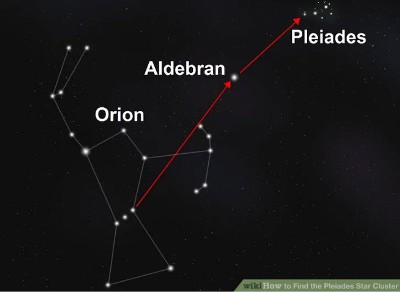

The Pleiades is such a vivid star cluster that the eye is drawn to it, and the same was true for ancient civilizations, north and south of the equator, who created wonderful legends to explain its seasonal appearances. (The Pleiades marks the summer in the south and dazzles winter’s northern skies. You can check out its placement in relation to the Orion and Taurus constellations below.)

Ešenvalds gathered six of these charming star myths – from the poetry of Native American tribes such as Pawnee, Zuni, Nez Perce and Inuit – to construct an approachable work that is fundamentally tonal and romantic in spirit. Its gentle dissonances have newish sparkle, even as the whole seems quite singable and speaks directly to the heart in the manner of centuries-old English cantatas, carols and hymns.

Ešenvalds gathered six of these charming star myths – from the poetry of Native American tribes such as Pawnee, Zuni, Nez Perce and Inuit – to construct an approachable work that is fundamentally tonal and romantic in spirit. Its gentle dissonances have newish sparkle, even as the whole seems quite singable and speaks directly to the heart in the manner of centuries-old English cantatas, carols and hymns.

The work opens with some broad Coplandesque trumpet oratory (the orchestra’s brass leadership sounded excellent throughout) in service of a Zuni tune that’s set to Tennyson’s lyrics; it develops the lovely image of the Pleiades star cluster as a “swarm of fire-flies tangled in a silver braid.” The prologue then segues into the old Inuit myth of Nanuk the Bear, who outruns a pack of dogs until they all fall right off the land’s edge together, where they are turned into the constellation in view.

Ešenvalds’ centerpiece is a slow-rising arc based on a Pawnee song that envisions the human spirit ascending together with Chakaa (the Pleiades). In its summoning of optimism, it’s a viable candidate for excerpting; it could easily stand on its own. Likewise the “Seven Dancers” tells the sweet story of seven boys who get carried away via a drum-thumping 5/4 nonsense rhyme to the point where they’re soaring over the treetops (a la “E.T.”) into the skies. I imagine that the advanced school choir folks in attendance – hearing the astounding polish and energy of the hundred-plus singers onstage prepared by chorus director Christopher Bell – will vow to give this number a try.

The Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus was led by Carlos Kalmar, whose choral showcase night was very well conceived: In addition to the Ešenvalds premiere were some stellar representatives from the 19th and 20th centuries – Brahms’ “Gesang der Parzen” (Song of the Fates), Bernstein’s “Chichester Psalms” with the confident boy soprano Bryce Abend, and Messiaen’s exquisite “O Sacrum Convivium” for unaccompanied chorus. I can’t think of much that could outshine this rich assembly of first-class choral pieces, except perhaps Bell’s sparkling rainbow-striped sneakers.

The short Messiaen work, which means “Oh, sacred feast,” could not really compete with the city’s natural soundscape, which is rarely ever actually silent. Still, it was worth being reminded of this gorgeous gem — a summoning of light filtered through stained glass.

Between Bernstein’s “Chichester Psalms” and the urban sounds, however, there was no contest. His muscular assembly of some of the Torah’s most famous Hebrew verses – from Psalms 2, 23, 100, 108, 131 and 133 – was riveting in the approaching night. It was a tremendous, complex effort, dramatically urgent and often fraught, then morphing into segments of aching beauty. The chorus deserves its own constellation for this one. And that cello solo from Psalm 131 (Kagamul alai naf’shi), which likens the soul to a weaned child of God, seems to me a masterstroke every time I hear it. Bravo to principal cellist Walter Haman, and to the cello foursome that ensued, for their very touching moments.

Kalmar’s forces closed with lines from Psalm 133 — “Behold how good and pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity” — that seemed downright plaintive despite their consoling hush. I doubt I am the only one who felt the gentle toll of Bernstein’s last phrases to be appropriate benediction for troubled times.

Related Links:

- Concerts and rehearsals are free: Go to the website calendar

- Detailed program notes are available: Click here to read in advance

- Highlights of the Grant Park Music Festival season: Read our picks at Chicago On the Aisle

Tags: Brahms, Bryce Abend, Carlos Kalmar, Chichester Psalms, Christopher Bell, Ēriks Ešenvalds, Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus, Leonard Bernstein, Olivier Messiaen, The Pleiades