CSO violist Max Raimi steps out as composer; Muti leads orchestra, chorus in Schubert Mass

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus with vocal soloists, conducted by Riccardo Muti at Orchestra Hall on March 22.

By Nancy Malitz

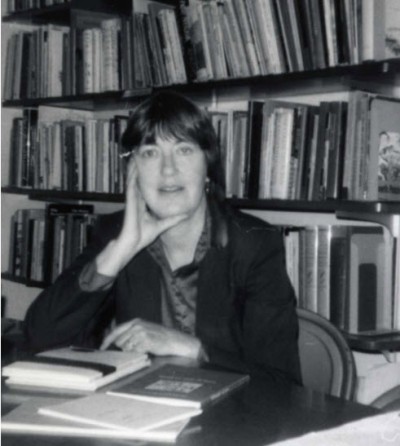

If you assume the legacy of 94-year-old poet Lisel Mueller is mostly lace and wistera, think again. This profound German-American bard, whose father was a dissident targeted by Nazis, arrived in the U.S. as a girl of 15. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1997, she has spent most of her adult life in Lake Forest, putting words together with ferocious precision.

In one poem, “Virtuosi,” Mueller writes of people starting over again in the shadow of violent history, and of the dazzling ways they tame their nightmares. “Cover your eyes: there’s one / walking on a thread / thirty feet above us … and she works without a net,” she writes, apropos of herself.

In one poem, “Virtuosi,” Mueller writes of people starting over again in the shadow of violent history, and of the dazzling ways they tame their nightmares. “Cover your eyes: there’s one / walking on a thread / thirty feet above us … and she works without a net,” she writes, apropos of herself.

A suite of three of Mueller’s keenly sentient poems, set to music by Max Raimi, a violist in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was given its world premiere March 22 by the CSO led by music director Riccardo Muti, with the vocal counterpart of a viola to intone them – the deep-voiced, yet high-flying mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong.

There are other composers who prize the viola and play it — among them Raimi’s contemporaries Sally Beamish, Brett Dean, and Kenji Bunch, whose “Dream Songs” was premiered at the Grant Park Music Festival in 2015. The viola-composer line goes way back, through Raimi’s teacher Lillian Fuchs at Juilliard to Hindemith and Paganini and even to Mozart, who enjoyed tending to the viola’s middle line when chamber music was the game.

Although Raimi makes his living primarily as a violist, he is quite active at composing. Muti had become aware of his talents as a go-to guy for chamber music, fight songs, soundtracks, concertos, whatever is needed.

Thus Raimi’s premiere became part of a special CSO showcase honoring the orchestra’s own: The Chicago Symphony Chorus, celebrating its 60th anniversary this season, dominated the entire second half of the concert with Schubert’s monumental Mass No. 6 in E-flat major, which had not been given by the CSO at Orchestra Hall since 1975. The magnum opus featured four top-flight solo singers in addition to DeShong, who lent her voice to that project as well.

When Mueller won her Pulitzer, Raimi read her poetry, was gobsmacked and sought her out; they’ve been friends ever since. He first set her words to music in 2002, and when Muti commissioned him to write something new, the composer went back to Mueller’s wellspring and chose “The Story,” about whiplash in a marriage of opposites; “An Unanswered Question,” about a caged human, the last of her race; and “Hope,” a touching litany by way of definition.

The music aims for cinematic impact; it’s aggressively muscular and moody, essentially romantic in gesture, with a blistering chromatic palette. DeShong is one of the few singers I can think of who would have no trouble cutting through it. Possessed of unusual range and vocal color, abundant strength and inherent dramatic intelligence, she gave the lines insistent emotional readings.

Each poem was colored by obbligatos that Raimi fashioned especially for CSO solo players. Principal clarinet Stephen Williamson added erupting melismatic lather to the first poem; principal bassoon Keith Buncke delivered touching existential musings to the second; and principal double bass Alex Hanna soared pretty much free of gravity in the third. Raimi and Muti made sure there were bows all around. If more than one listener in the audience seeks out Mueller’s achingly beautiful poetry as a result of this high-minded tribute, the night was surely won.

Each poem was colored by obbligatos that Raimi fashioned especially for CSO solo players. Principal clarinet Stephen Williamson added erupting melismatic lather to the first poem; principal bassoon Keith Buncke delivered touching existential musings to the second; and principal double bass Alex Hanna soared pretty much free of gravity in the third. Raimi and Muti made sure there were bows all around. If more than one listener in the audience seeks out Mueller’s achingly beautiful poetry as a result of this high-minded tribute, the night was surely won.

Schubert’s huge, dramatically magnificent and technically ambitious Mass No. 6 received a radiant performance by the Chicago Symphony Chorus. He composed the work just months before his death at age 31. Schubert had become mesmerized by the contrapuntal brilliance of Handel, an elixir as heady as Bach, and earnest homage is all there in this humble and transcendent Mass filled with the sense of life’s fleeting contradictions.

Soprano Amanda Forsythe, tenors Paul Appleby and Nicholas Phan, and bass Nahuel Di Pierro, joined DeShong in the choir area. When Schubert spotlighted them, as did in the intimate Benedictus and the Et incarnatus est of the Credo, it was as if the chorus itself was flowering from within.

Soprano Amanda Forsythe, tenors Paul Appleby and Nicholas Phan, and bass Nahuel Di Pierro, joined DeShong in the choir area. When Schubert spotlighted them, as did in the intimate Benedictus and the Et incarnatus est of the Credo, it was as if the chorus itself was flowering from within.

The Chicago Symphony Chorus was created 60 years ago this month at the behest of music director Fritz Reiner, who brought in Margaret Hills to found a professional ensemble. Duain Wolfe, who is now in his 24th season as its director, has cultivated it with rare dedication, of which the Schubert was indicative. The sense of the conflicted human soul in the final movement, the Agnus Dei, was something particularly to treasure.

The finale seemed both familiar and threatening, its initial “lamb of God” motive hammering with a dread in subtle kinship to a Dies Irae. (The Agnus Dei tune itself, which one finds in Bach, is also a repeating chain in Schubert’s musical DNA.)

To hear these restless phrases alternate with the Chicago Symphony Chorus’ sweet petition of Dona Nobis Pacem, as if repeating might make it so, was to appreciate the refined sensibility of Muti’s carefully measured performance, and the combined intelligence of an ensemble that can parse the experience of being human in such a beautiful way.

Tags: Amanda Forsythe, Chicago Symphony Chorus, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Delizabeth DeShong, Duain Wolfe, Franz Schubert, Lisel Mueller, Max Raimi, Nahuel Di Pierro, Nicholas Phan, Paul Appleby, Riccardo Muti