András Schiff, pianist and conductor, doubles the pleasure of an elegant night with the CSO

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, with pianist-conductor András Schiff, at Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

The consummate musicianship of András Schiff is well known to Chicago aficionados of the piano. He’s a familiar face in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s annual recital series. Yet even his most ardent fans might have been surprised by Schiff’s masterly conducting – from the keyboard and in strictly orchestral fare – in a diverse and delightful program with the CSO.

Schiff doubled as soloist and conductor in vibrant concerto performances of Bach and Beethoven in the evening’s second half, after the price of admission had already been well repaid by his spirited and stylish readings of orchestral works by Haydn and Bartók. Moreover, the pleasure was compounded by hearing the CSO reduced to a sparkling chamber ensemble for the entire program.

To choose a gem from a treasury, it’s possible the best came first at the concert I heard Nov. 3 – an exhilarating, finely crafted and endlessly witty turn through Haydn’s Symphony No. 88. Eschewing a score (and a baton), Schiff indeed offered a hand-crafted take on this elegant music that simultaneously honored its 18th-century locus and showed how it set the stage for the bold new voice of Beethoven.

Schiff had Haydn’s subtle intricacies and broad humor equally in hand: the stately rhythms of the opening movement, the dramatic bearing of the ensuing variations that brought to mind their counterpart in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the easy grace of the minuet. The 88th’s finale invites a blistering pace, and I recall years ago watching Leonard Bernstein turn the Vienna Philharmonic loose at lightning speed. But Schiff didn’t take the tempo to that extreme. It was plenty quick, but also agile, sly and contoured to knowing purpose.

One might not think of a Haydn symphony as an orchestral showpiece, but the CSO’s sheer virtuosity – magnified by its reduced numbers – was never more compelling than in the finesse demanded by this transparent music. It was a heady start to a night of intimate rapport between maestro and orchestra.

Bartok’s charming Divertimento for Strings melded perfectly into the program’s classical disposition. Even as the three-movement work echoes the rhythms and modes of Hungarian folk song, it also harkens back to Viennese tradition – including a very funny parody of the polka near its conclusion. This is Bartók in a mostly sunny frame of mind, despite the poignancy of the work’s central movement.

Schiff, a native of Budapest who has recorded most if not the entire body of Bartók’s prodigious piano output, shaped a performance at once lyrical and deeply resonant. The CSO strings responded with lustrous playing and, notably in a last-movement excursion into a wild gypsy dance, high spirits.

Schiff, a native of Budapest who has recorded most if not the entire body of Bartók’s prodigious piano output, shaped a performance at once lyrical and deeply resonant. The CSO strings responded with lustrous playing and, notably in a last-movement excursion into a wild gypsy dance, high spirits.

For the concert’s second half, in which he conducted from the keyboard, Schiff turned the piano – with its lid up – at an angle where he could see every player. In musical essence as well as line of sight, the communication between maestro and orchestra was tellingly clear.

Schiff’s delivery of Bach’s brief but brilliant Keyboard Concerto No. 5 in F minor was exactly what one might expect from one of the world’s foremost authorities on Bach: glittering, articulate, precisely voiced, propulsive. The ovation that answered this 10-minute work left no doubt that these listeners, who filled perhaps two-thirds of Orchestra Hall, knew exactly why they were there.

Double-duty performances by a musician trying to serve as both soloist and conductor all too often serve neither. But in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1, Schiff managed both tasks efficiently and purposefully in a collaboration between keyboard and orchestra that was nothing short of thrilling.

Amid a piano performance that once more demonstrated the quality of his art, a marvelous blend of intellect and poetry and impeccable technique, Schiff managed to provide specific guidance to the CSO. Piano and orchestra were one shining ensemble, classically proportioned and classically fluent.

But my favorite moment came in Beethoven’s formidable first-movement cadenza, which concludes with two big, distinctly separated chords. As he came down on the final chord, Schiff leaned toward the audience with just a bit of a mug, a la Victor Borge. The house broke into laughter. The movement ended; the moment was over. These listeners knew their man. And when the concerto, and with it the concert, ended, their appreciation exploded.

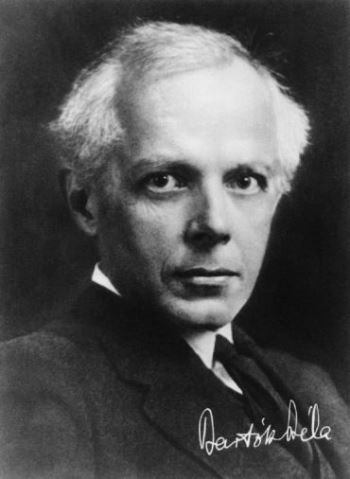

(Photo of András Schiff conducting © Chris Lee, courtesy New York Philharmonic)

Tags: Andras Schiff