‘Die Walküre’ at Lyric Opera: Heroic singing, lots of blood, and Wagner caught in a muddle

Review: “Die Walküre” by Richard Wagner, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago through Nov. 30. ★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

There are times in opera when great singing rises above problematic production. Voices triumph over Konzept. But not even a glorious performance by bass-baritone Eric Owens – or the exemplary musical leadership of Andrew Davis – could compensate for the sum of gruesome design and muddle-headed staging heaped upon Wagner’s “Die Walküre” at Lyric Opera of Chicago.

This “Walkure” is the second installment in the Lyric’s four-year project to create an all-new cycle of Wagner’s prodigious tetralogy “Der Ring des Nibelungen” – the legend of the curse of the Rhine gold, and how its promise of insuperable power first corrupted the gods, then led inexorably to their destruction. It’s a 17-hour morality tale that took Wagner some 25 years to write (both text and music), and an ever-apposite mirror to the human imperfections of venality and greed.

If the Lyric’s take last season on the first opera in the “Ring” cycle, “Das Rheingold,” was off the wall with its cartoonish puppet-giants, it was also witty, focused and attuned to the spirit of the work. As the set-up piece, “Das Rheingold” explains how the misshapen dwarf Alberich forswears love in order to seize the Rhine Maiden’s lump of gold and forge it into an all-powerful ring, and how Wotan, king of the gods, tricks Alberich out of the ring only to be forced to surrender it in payment for the construction of his fine new palace, Valhalla.

If the Lyric’s take last season on the first opera in the “Ring” cycle, “Das Rheingold,” was off the wall with its cartoonish puppet-giants, it was also witty, focused and attuned to the spirit of the work. As the set-up piece, “Das Rheingold” explains how the misshapen dwarf Alberich forswears love in order to seize the Rhine Maiden’s lump of gold and forge it into an all-powerful ring, and how Wotan, king of the gods, tricks Alberich out of the ring only to be forced to surrender it in payment for the construction of his fine new palace, Valhalla.

Because he cannot simply steal the ring back, lest by such an overtly corrupt act he invalidate his authority altogether, Wotan must find an independent agent who on his own initiative might repossess the ring. But of course Wotan might nudge such a development along, which brings us to “Die Walküre.” Mating with a human woman, the god-king sires two mortal children: Siegmund and Sieglinde. They are separated as babes when, one day while her father and brother are away, Sieglinde is stolen by an enemy clan and forced into a marriage of servitude to a savage chap called Hunding.

“Die Walküre” – the Valkyrie, one of Wotan’s immortal warrior-daughters who appears later in the opera – begins with the grown, orphaned Siegmund (tenor Brandon Jovanovich) showing up, exhausted from flight, at the door of Hunding’s hut. There he finds Sieglinde (soprano Elisabet Strid) leashed by a heavy chain while her husband is out hunting. The siblings do not at first recognize each other.

It bears mentioning here that Wagner’s idea of opera was drama elevated by music: perfect theater, or what he called Gesamtkuntswerk, a completely integrated artwork. And this first scene between the handsome young stranger and the desolate woman in chains appeared headed toward all of that, splendid in every aspect both musical and dramatic.

Jovanovich’s effortless, full-bodied and expressive singing was matched by Strid’s blend of lustrous sound and keening desperation. Then Hunding showed up, Sieglinde’s chains came off, and director David Pountney’s scheme of interaction between the lusty youngsters soon turned bizarre.

Jovanovich’s effortless, full-bodied and expressive singing was matched by Strid’s blend of lustrous sound and keening desperation. Then Hunding showed up, Sieglinde’s chains came off, and director David Pountney’s scheme of interaction between the lusty youngsters soon turned bizarre.

Pressing Siegfried to tell his woeful history, Hunding realizes that his guest is also his sworn enemy. Hunding informs Siegmund that at sunup, his life is forfeit. Whereupon the host retires for the night. And Sieglinde transforms, in this staging, from battered wife to something like an abused puppy, if not a mad woman. Strid rolled about on the floor, now shrinking into a fetal curl, now pawing Siegmund – to put it euphemistically. Seigmund returned her ardor in kind. When he spotted the sword Wotan has left for him, buried up to the hilt in an ash tree at the center of Hunding’s parlor, Siegfried brandished it with visually double-edged meaning – the stuff of Shakespearean farce.

In short time, the kids have put two and two together. They may be long lost siblings, but they’re also each other’s metaphorical springtime, which Jovanovich and Strid declared in a radiant turn through perhaps the opera’s most inspired music. This despite the director’s odd blocking. These awakening lovers sing about the light in each other’s eyes, the magic in each other’s gaze – all while looking away from each other, from far corners of the stage. Hello! This is a love scene.

Siegmund addresses Sieglinde as his beloved sister and wife, and off they race into the spring night – though not very far in Pountney’s reckoning. Lest viewers failed to grasp the basic urge at work here, it was spelled out. The steaming lovers tumbled to the ground to make the beast with two backs, countering Wagner’s poetic consummation in the orchestra with a gesture obvious and crass.

The crisis of “Die Walkure” arises in Act II, where we first meet Brünnhilde, the opera’s eponymous Valkyrie and Wotan’s favorite among his warrior-daughters. In effect, Brünnhilde (the vocally shining Christine Goerke) is Wotan’s second self, his will. She is certainly his right hand, and in the coming clash between Hunding and Siegmund, the Valkyrie is armed and ready to ensure Siegmund’s triumph – as well as his getaway with Sieglinde and the unborn child who will retrieve the all-powerful ring.

The crisis of “Die Walkure” arises in Act II, where we first meet Brünnhilde, the opera’s eponymous Valkyrie and Wotan’s favorite among his warrior-daughters. In effect, Brünnhilde (the vocally shining Christine Goerke) is Wotan’s second self, his will. She is certainly his right hand, and in the coming clash between Hunding and Siegmund, the Valkyrie is armed and ready to ensure Siegmund’s triumph – as well as his getaway with Sieglinde and the unborn child who will retrieve the all-powerful ring.

Ah, but a speed bump looms ahead: Wotan’s wife Fricka (Tanja Ariane Baumgartner), protectress of marriages, is in a fuming rage over Wotan’s not-so-sly scheme and insists that Siegmund must die by Hunding’s hand. Baumgartner is a majestic Fricka, in presence and voice alike. The goddess has right on her side; Wotan knows it, and he caves. He will call Brünnhilde off. In supreme voice and with compelling dramatic force, Owens delivered what is basically a long lecture to Brünnhilde, insisting that she carry out his command, though it’s the furthest thing from his heart’s wish – ambivalence that the Valkyrie fully grasps.

And in the end, she doesn’t do Wotan’s bidding. In a tormented, brilliantly sung confrontation between Jovanovich’s Siegmund and Goerke’s Brünnhilde, the Valkyrie capitulates and thus elicits Wotan’s irreversible condemnation. She will be banished, lose her immortal condition and fall into a deep sleep on a high rock, there to await subjugation to the first man who comes upon her.

This is the scene of Wotan’s famous farewell, which Owens infused with equal parts of tenderness and stern resolve. But again, Pountney seemed unsure about how to maneuver his characters. Goerke did little more than shrink away in horror, then plunge back in heartfelt appeal. Away and back, yoyo-like.

This is the scene of Wotan’s famous farewell, which Owens infused with equal parts of tenderness and stern resolve. But again, Pountney seemed unsure about how to maneuver his characters. Goerke did little more than shrink away in horror, then plunge back in heartfelt appeal. Away and back, yoyo-like.

All that, however, comes at the end of the opera. Before we get there, we must slog through knee-deep blood in what I might call the Charnel House of Chicago: the gathering place of the Valkyries, whose main task is to collect the souls of fallen mortal warriors for transfer into the divine military.

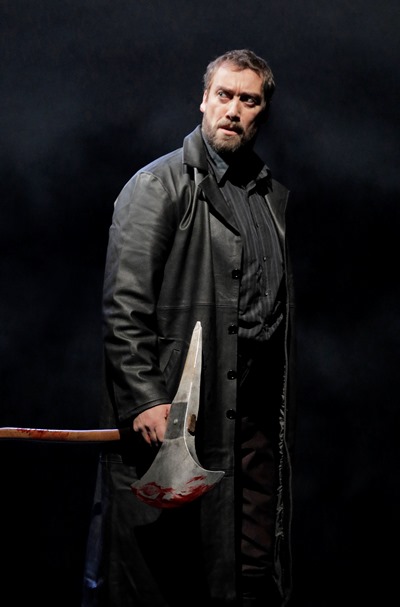

Again unwilling to trust the viewer’s imagination, the “Ring” project’s late designer, Johan Engels, and his successor, Robert Innes Hopkins, give us transparent, full-length body bags containing corpses and oozing with blood. Other bodies are suspended in netting upstage. The arriving Valkyries – mounted on crane-supported horses — are likewise smeared with the rouge spills of their task.

In the midst of this gory spectacle sounded the Valkyries’ well-known anthem, music that now seemed almost incidental, all but untrackable. Only when I closed my eyes could I really hear the sonorous magic that Andrew Davis drew from the Lyric Opera Orchestra: music rhythmically sprung, vital, rich, clear and embracing. Unstained by that rank visual carnage.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Review of ‘Das Rheingold,’ the Lyric’s first ‘Ring’ installment: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

Tags: Ain Anger, Andrew Davis, Brandon Jovanovich, Christine Goerke, Elisabet Strid, Eric Owens, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner

1 Pingbacks »