Pianist Gerstein measures himself against pair of Olympians, and displays solid gold mettle

Review: Pianist Kirill Gerstein in recital at Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

As prodigious as it was unusual, pianist Kirill Gerstein’s recital June 11 at Orchestra Hall bundled the double rarity of Brahms’ ambitious early Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor and the full dozen of Liszt’s spectacular “Transcendental” Etudes.

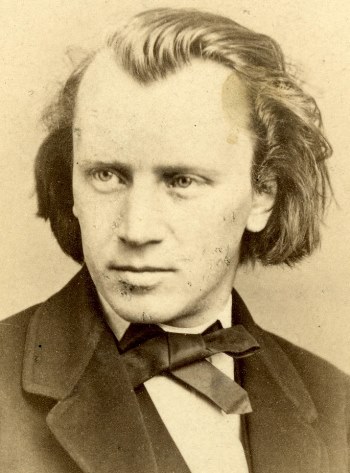

Both works have their historical quirks. Brahms was 19 years old when he turned out the F-sharp minor Sonata, his first work in the form. It is nonetheless engraved in history as No. 2, because the next year he produced a Sonata in C major that he felt would make a better first impression on the public and critics. So the C major became his calling card, Op. 1, and the F-sharp minor was designated as Op. 2.

That Brahms the 20-year-old composer would have, well, soft-pedaled the F-sharp minor Sonata only indicates how self-critical he was from the outset of a career in which he routinely destroyed any his manuscripts that he deemed unsuitable for the world’s ears; and there apparently were many.

That Brahms the 20-year-old composer would have, well, soft-pedaled the F-sharp minor Sonata only indicates how self-critical he was from the outset of a career in which he routinely destroyed any his manuscripts that he deemed unsuitable for the world’s ears; and there apparently were many.

But this brash, confident, grand sonata proclaims a formidable talent, and Gerstein, now age 37, imbued it with a young man’s bravura spirit. Brahms must have been some pianist. The work’s technical requirements are considerable, but no less striking is the pervasive lyricism that would become the composer’s hallmark in his chamber music and symphonies alike. (The F-sharp minor Sonata dates from 1852; it would be another 24 years before the critically circumspect Brahms would allow a first symphony to see the light.)

The Sonata’s opening movement is nothing less than the announcement of new pianist-composer to be reckoned with. It is aggressive, brilliant to the point of flamboyance, and Gerstein tossed off its handfuls of notes with unstinting flair. Likewise, both the scherzo and finale demand a certain pianistic athleticism that Gerstein came amply prepared to display.

If all that energy bespoke a youthful author, the slow movement perhaps most convincingly argued for a composer thoughtful, sensitive, serious beyond the conventional disposition of youth. In Gerstein’s hands, this music, marked “con espressione,” afforded a gently ruminative interlude, a breather amid the virtuosic torrents that otherwise dominate Brahms’ formal coming out.

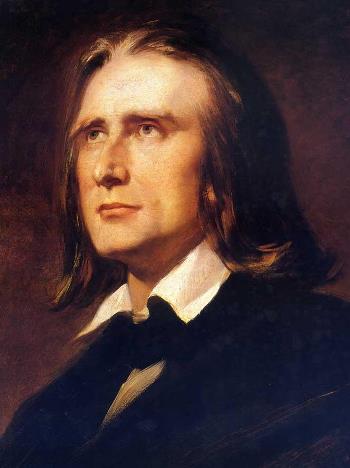

Liszt’s “Transcendental” Etudes likewise spring from youth – indeed, this work that remains a benchmark of virtuosity began life as the scrawl of a 15-year-old prodigy. But that was just its beginning. About a decade later, in 1837, the now fully formed Liszt, pianist extraordinaire, revisited his 12 Etudes, elaborating them into a series of monumental exercises that perhaps he alone in the world could play. In time, even he could see that was a problem. And so, to make these Études d’exécution transcendante approachable by mere mortals, Liszt went back to the drawing board again in 1851 and buffed out some of the more daunting passages. It is this version that’s usually performed today, and that is what Gerstein took on.

Liszt’s “Transcendental” Etudes likewise spring from youth – indeed, this work that remains a benchmark of virtuosity began life as the scrawl of a 15-year-old prodigy. But that was just its beginning. About a decade later, in 1837, the now fully formed Liszt, pianist extraordinaire, revisited his 12 Etudes, elaborating them into a series of monumental exercises that perhaps he alone in the world could play. In time, even he could see that was a problem. And so, to make these Études d’exécution transcendante approachable by mere mortals, Liszt went back to the drawing board again in 1851 and buffed out some of the more daunting passages. It is this version that’s usually performed today, and that is what Gerstein took on.

One can be sure of the version at hand by the catalog designation: The ultra-virtuosic setting of 1837 bears the indication S. 137; the 1851 revision is S. 139. But let there be no doubt about the pianistic wherewithal required to play the “Transcendental” Etudes in Liszt’s final adjustments.

They can be breathtakingly intricate, that intricacy often spun out at breakneck speed. Moreover, apart from a fleeting Preludio, these are grand-scaled pieces, most of them bearing Liszt’s own evocative titles: tone poems for piano – one of which, “Mazeppa,” Liszt reworked as a symphonic poem. If nothing else, this sequence running more than an hour is a tour de force of memorization.

Gerstein pressed through the astounding Etudes with leonine strength, agility and grace.

Gerstein pressed through the astounding Etudes with leonine strength, agility and grace.

To say nothing of speed. In explosive episodes like “Mazeppa,” “Wilde Jagd” (Wild hunt) and the untitled Allegro agitato molto, the pianist swept over cascading phrases with unflappable elan and hair-raising power.

Where elegance was paramount, as in “Ricordanza” (Remembrance), “Paysage” (Landscape) and “Feux-follets” (Will-o’-the-wisp), Gerstein adroitly suborned technical demands to expressive finesse. In these airy romps and ruminations, he produced sounds of gossamer lightness.

His closing dash through “Chasse-neige” (Swirling snow) was greeted by whoops and cheers, and shouts of “Encore!” The visibly weary pianist declined.

Two remarkable hours earlier, Gerstein had opened this recital in quite another place, with a crystalline turn through four works of Bach simply titled Duets (BWV 802-805), from Part 3 of the “Clavier-Übung” (Keyboard practice). There was an arresting strain of intellectual calm and clarity in his playing. Nothing to hint of the pianistic storms about to descend.

Related Link:

- Gerstein has recorded the “Transcendental” Etudes on the Myrios Classics label: Go here for CD or download

- Ten pianists will present recitals in the 2018-19 Symphony Center Presents series: Read the details here

Tags: Kirill Gerstein