Pianist Murray Perahia forges an alluring path from bright Bach through a Beethoven thicket

Review: Recital by Murray Perahia, May 7 in the Symphony Center Presents piano series at Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Musical virtuosity is the sum of diverse parts, only the most obvious of which is great technical prowess. Pianist Murray Perahia’s recital May 7 at Orchestra Hall offered a veritable punch list of the qualities that add up to consummate musicianship.

Indeed, Perahia’s program was as effectively built as it was rewardingly performed — a stylistic sweep from the last of Bach’s six “French” Suites through Schubert’s Four “Impromptus,” D. 935, to Beethoven’s monumental Sonata in B-flat, Op. 106 (“Hammerklavier”).

Indeed, Perahia’s program was as effectively built as it was rewardingly performed — a stylistic sweep from the last of Bach’s six “French” Suites through Schubert’s Four “Impromptus,” D. 935, to Beethoven’s monumental Sonata in B-flat, Op. 106 (“Hammerklavier”).

Just turned 70 years old, Perahia stands among the pianistic lions of our time. He’s also one of the foremost interpreters of Bach. It is a profoundly cultivated spiritual rapport, and it shone in Perahia’s ethereal turn through the eight dances that form the “French” Suite No. 6 in E major.

Words like ethereal and profound might not leap to mind in connection with a Baroque dance suite, but they applied pervasively to Perahia’s sparkling, rhythmically sprung, altogether lighter-than-air performance. If Bach’s “French” Suites are more ebullient than his preceding “English” Suites, the French dances’ depth and challenge lie in their very buoyancy and their elegance. And that was the joy of Perahia’s account.

With the exception of a ruminative, even wistful Sarabande, the pianist imbued the likes of Allemande, Gavotte, Polonaise and, to be sure, the final Gigue with an irresistible vitality edged with impeccable finesse. If this was Bach for today’s world, it made at least one listener grateful for the resources of a proper modern piano, and for the imagination, intellect and artistic wherewithal of a complete pianist.

With the exception of a ruminative, even wistful Sarabande, the pianist imbued the likes of Allemande, Gavotte, Polonaise and, to be sure, the final Gigue with an irresistible vitality edged with impeccable finesse. If this was Bach for today’s world, it made at least one listener grateful for the resources of a proper modern piano, and for the imagination, intellect and artistic wherewithal of a complete pianist.

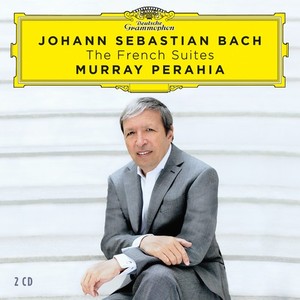

Perahia has recorded all six of the “French” Suites in a double-CD set that marks his debut with Deutsche Grammophon. Released in October 2016, it’s an endlessly illuminating survey that reflects both the more worldly side of Bach — perhaps in the spirit of the “Brandenburg” Concertos — and the artistic bond between composer and pianist.

Schubert’s “Impromptus,” D. 935, written near the end of his brief life, took Perahia into quite another world – one of dark song and meandering contemplation. As the title suggests, the “Impromptus” evoke an aura of improvisation: It is not hard to imagine the prodigious and facile composer actually turning out these discursive pieces as they came to him — in single flourishes, extempore and unamended. Much like a modern-day jazz musician.

For that matter, the fascination of the “Impromptus,” as in jazz, lies substantially in their often surprising and bold harmonic progressions; that and the evolving thematic ideas that show us the rigor and thrust of a musical mind that could create the “Great” C major Symphony as readily as “Gretchen am Spinnrade.”

Perahia’s performance was like a series of quests, searches for each elusive essence in these four flights of fancy. The grandly formed first of the group showed the pianist’s command of structure; the third, where one of Schubert’s typically beguiling tunes leads to five brilliant variations, displayed Perahia’s flair for characterization. The last impromptu, a gypsy-flavored romp, allowed the pianist to indulge in sheer frolic.

This quasi-improv Schubert made a perfect set-up for Beethoven’s magisterial “Hammerklavier” Sonata, a sea-change work that remains as astounding now as it was at its birth two centuries ago. To Anglophones, there’s a specific weight to the word Hammerklavier – German for fortepiano, predecessor to the modern piano and Beethoven’s own culturally proud term for his new sonata – that exactly suits Op. 106. It is formidable, with a capital F.

This quasi-improv Schubert made a perfect set-up for Beethoven’s magisterial “Hammerklavier” Sonata, a sea-change work that remains as astounding now as it was at its birth two centuries ago. To Anglophones, there’s a specific weight to the word Hammerklavier – German for fortepiano, predecessor to the modern piano and Beethoven’s own culturally proud term for his new sonata – that exactly suits Op. 106. It is formidable, with a capital F.

Perhaps not so much the opening movement. One might even say its impulsive fanfares together with the ensuing scherzo, brief and jocund, form something of a prelude to the vast slow movement and tremendous fugal finale that make up the core of the work.

What Perahia did with the early movements was assured and engaging, and yet it scarcely hinted at the magnificence he would bring to the work’s main chapters. The sprawling Adagio, which unfolds like some unbounded philosophical musing, challenges a pianist just to keep it together. No problem here: It would have been impossible to turn one’s mind away from Perahia’s concentrated line.

Likewise, the pianist made such heated, mesmerizing work of the finale’s contrapuntal splendor that the ear followed on faith. Like Beethoven’s later, ever-amazing “Grosse Fuge” for string quartet, Op. 133, the fraught music that ends this sonata is no mere fugue, but rather a fugal thicket. Beethoven writes according to his unbridled imagination and dares both pianist and listener to go with him. Perahia might have been the composer, so surely – and freely – did he proceed, blazing the trail, lighting the way.

Likewise, the pianist made such heated, mesmerizing work of the finale’s contrapuntal splendor that the ear followed on faith. Like Beethoven’s later, ever-amazing “Grosse Fuge” for string quartet, Op. 133, the fraught music that ends this sonata is no mere fugue, but rather a fugal thicket. Beethoven writes according to his unbridled imagination and dares both pianist and listener to go with him. Perahia might have been the composer, so surely – and freely – did he proceed, blazing the trail, lighting the way.

Related Links:

- Maurizio Pollini plays a Chopin program May 28 in the Symphony Center Presents piano series: Details at CSO.org

- Complete 2017-18 SCP Piano Series: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Murray Perahia