With Haitink sidelined, James Conlon steps in and leads CSO, singers in Mahler to remember

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by James Conlon; mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly, tenor Richard Cox. Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

When the Chicago Symphony Orchestra released its program schedule for the current season, among the brightest highlights – one of those don’t-miss concerts – was Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde,” to be led by Bernard Haitink, who at age 88 is unsurpassed among Mahler conductors today. Then, just days before the performance weekend, March 30-April 1, Haitink canceled due to illness.

The prospect of a season peak suddenly was looking like a major disappointment. Amazingly enough, on almost no notice, the CSO turned to an old friend, an experienced, highly regarded conductor who was available to take on what is arguably Mahler’s masterwork. Indeed, James Conlon, who served as music director of the Ravinia Festival — the Chicago Symphony’s summer home — from 2005-15, did more than stand in: He shepherded the CSO and two very capable singers through a richly hued and conceptually profound account of “Das Lied von der Erde” that will long be remembered.

The twists didn’t end with Conlon’s 11th-hour rescue. Tenor Stephen Gould sang through illness on the first night before withdrawing, to be replaced by Richard Cox. I didn’t hear Gould, but on the second night Cox turned in one of the smartest, most nuanced performances I’ve heard in Mahler’s technically exacting and psychologically fraught music. And he was well matched by mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly, who in this “Song of the Earth” summoned the qualities of both tender mortal and mystic earth-mother.

The twists didn’t end with Conlon’s 11th-hour rescue. Tenor Stephen Gould sang through illness on the first night before withdrawing, to be replaced by Richard Cox. I didn’t hear Gould, but on the second night Cox turned in one of the smartest, most nuanced performances I’ve heard in Mahler’s technically exacting and psychologically fraught music. And he was well matched by mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly, who in this “Song of the Earth” summoned the qualities of both tender mortal and mystic earth-mother.

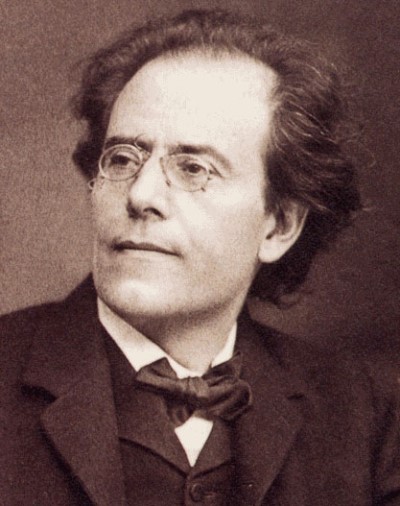

Based on verses by various ancient Chinese poets, “Das Lied von der Erde” is essentially a song-symphony in six movements, each episode dealing with an aspect of the human condition – vitality, optimism, isolation, disillusionment – until the last and most spacious chapter confronts the inevitability of death. The songs are not so much accompanied by the orchestra as they are immersed in its delicate tone painting. Through and through, the finely brushed orchestral score evokes – almost as graphically as the texts themselves – the joy and beauty, irony and despair of life’s arc, before reaching a denouement of resignation and acceptance.

Conlon led the CSO in a bracing, eloquent, pervasively brilliant performance that was especially notable for the many fine moments by the woodwind principals. Alex Klein’s oboe accents were everywhere, whether edged and penetrating or redolent of warmth. Likewise, flutist Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson and clarinetist Stephen Williamson, often in combination, contributed a sensual luster to this wide-angle snapshot of man’s fate.

Conlon led the CSO in a bracing, eloquent, pervasively brilliant performance that was especially notable for the many fine moments by the woodwind principals. Alex Klein’s oboe accents were everywhere, whether edged and penetrating or redolent of warmth. Likewise, flutist Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson and clarinetist Stephen Williamson, often in combination, contributed a sensual luster to this wide-angle snapshot of man’s fate.

And yet it is a song-cycle; the poems tower in their framing of the human lot, its passion and bleak comedy. Two of the tenor’s three songs dwell on the dark side – the opening “Drinking Song of Earth’s Sorrow” and “The Drunkard in Spring.” But it also falls to the tenor to sing about youth, that state of careless confidence and assumed immortality. Cox was captivating, his voice authoritative, his inflection precise, aggressive, knowing.

Beauty is the mezzo-soprano’s province – and loneliness; then, finally, the leave-taking of it all. Connolly was majestic, not so much in the size of her voice but in its suppleness and in the intelligence that lent her words scope and conviction. “Der Abschied” (The Farewell), Mahler’s vast song of transmigration from earthly cares, was a thing of bittersweet splendor, and a perfect collaboration between singer and conductor, between text and the nuanced gestures of the orchestra.

When Connolly’s last dying phrases of “Ewig, ewig…” (Forever, forever) had passed into silence, Conlon kept one hand high in the air, an injunction against any other sound – which the audience observed with pin-drop respect for a good 20 seconds or more. Then the torrent came, a huge ovation for what was, after all, a CSO season highlight.

When Connolly’s last dying phrases of “Ewig, ewig…” (Forever, forever) had passed into silence, Conlon kept one hand high in the air, an injunction against any other sound – which the audience observed with pin-drop respect for a good 20 seconds or more. Then the torrent came, a huge ovation for what was, after all, a CSO season highlight.

The concert began with a hardly less beguiling performance of Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 in B minor (“Unfinished”), whose radiant surfaces and dark interiors the CSO evoked in an effortless lyric flow. Here was Conlon as poet-conductor, manifest master of Schubert’s unfinished yet self-sufficient drama without words.

Related Links:

- Preview of Chicago Symphony’s complete 2016-17 season: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle