In ‘Hamilton’ immersion, Chicago school kids embroider the musical with riffs of their own

Report: To explore reasons behind its rhymes, “Hamilton” partners with foundations to get 20,000 teens into Chicago’s hottest show.

By Nancy Malitz

I wish every adult attending the hit musical “Hamilton” could see it the way nearly 20,000 Chicagoans in their mid-teens will experience it over the coming months. And not just because of the $10 tickets for a show that generally costs hundreds of dollars.

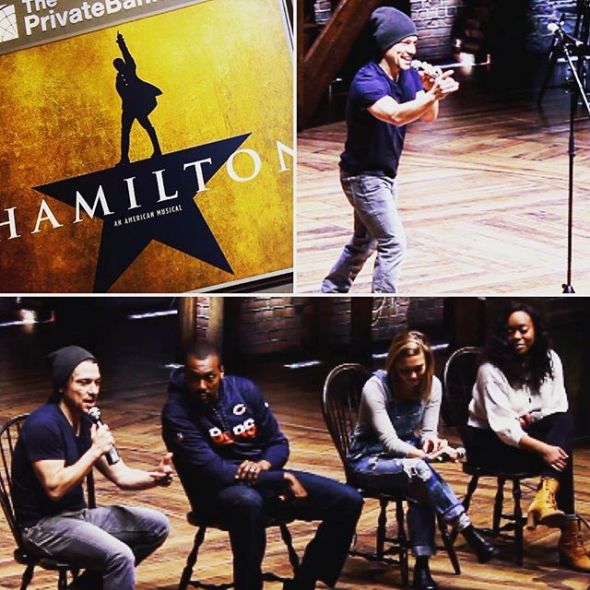

At an all-student matinee I attended in mid-March – one of ten at PrivateBank Theatre that are scheduled before the academic year ends this spring – the young people from 20 local high schools, college prep and career academies arrived super-prepared. When it comes to the fine points of Founding Fathers history, these student audience can run circles around your average showbiz fan. They’ve had weeks of study using writings from the era and they have answered their teachers’ mandates to respond by re-envisioning the basic history in artistic creations of their own.

What each student is given — through this curriculum-rich opportunity subsidized by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, the Rockefeller Foundation and a group of families and foundations with Chicago ties — is much more than a ticket, although a full-length performance of the show featuring the marquee artists and all the trimmings is certainly the main event of these visits.

The daylong experience includes an opportunity for students to submit their own questions to the performers, some of whom are not so long out of high school themselves; and it provides a showcase for about a dozen brand new, history-inspired numbers created and performed by students, who venture onto the the award-winning rope-and-pulley strewn “Hamilton” set to perform for the packed house of cheering fans.

The daylong experience includes an opportunity for students to submit their own questions to the performers, some of whom are not so long out of high school themselves; and it provides a showcase for about a dozen brand new, history-inspired numbers created and performed by students, who venture onto the the award-winning rope-and-pulley strewn “Hamilton” set to perform for the packed house of cheering fans.

The students’ day begins before 10 a.m. with the ballet of the yellow buses along Monroe Street in the Loop. Chaperoned groups from all across town quickly disappear into the theater in timed arrivals, section by section, as if for a gathering of the clans. The awesome perks that come next include the morning-long company of Miguel Cervantes — the amiable star who plays Alexander Hamilton — dressed for the first half of his day in street clothes.

Many Americans may be unaware that Alexander Hamilton was — as the musical’s creator and original title role star Lin-Manuel Miranda put it — a Caribbean-born “bastard, orphan son of a whore” who grew up to be “a hero and a scholar, the ten-dollar Founding Father without a father.” Hamilton’s recipe for success — getting ahead by “workin’ a lot harder, bein’ a lot smarter, bein’ a self-starter” — still resonates among immigrant families today.

Many Americans may be unaware that Alexander Hamilton was — as the musical’s creator and original title role star Lin-Manuel Miranda put it — a Caribbean-born “bastard, orphan son of a whore” who grew up to be “a hero and a scholar, the ten-dollar Founding Father without a father.” Hamilton’s recipe for success — getting ahead by “workin’ a lot harder, bein’ a lot smarter, bein’ a self-starter” — still resonates among immigrant families today.

And if the student audiences reflect Chicago’s own racial and ethnic mix, then so does the “Hamilton” cast. Jonathan Kirkland, for example, who plays the role of George Washington, is African-American. As is Wayne Brady, the well-known TV star who recently took up the role of Hamilton’s rival Aaron Burr.

Cervantes revved up a young mid-March crowd and acted as emcee for the student performers, from 12 of the schools, who were invited to perform. What a rush it must have been to present their own probing riffs on lessons learned from Alexander Hamilton’s story and the birth of the American nation. Employing rap and freestyle, dramatic sketch and spoken word, these student creations added urgent contemporary relevance with their insightful lyrics and newly minted rhymes.

One of the liveliest rap numbers, performed early on, was a rallying cry against “British Troops,” performed by three friends from the Camelot Academy of West Garfield Park, who made full use of the stage floor. The confident trio had already enjoyed some competitive success together in Chicago’s second annual Black History Bowl. They said they found their beat emerging naturally as they did the research to put their facts together.

One of the liveliest rap numbers, performed early on, was a rallying cry against “British Troops,” performed by three friends from the Camelot Academy of West Garfield Park, who made full use of the stage floor. The confident trio had already enjoyed some competitive success together in Chicago’s second annual Black History Bowl. They said they found their beat emerging naturally as they did the research to put their facts together.

Hezekiah Shaw Jr., from Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School, showed similar aplomb when the music accompanying his rap number, “Wheatley,” failed to materialize, so he freestyled his tribute to America’s first published black author, who spent many years a slave.

Lyricist Cynthia Moreno and guitarist Jesus Martinez, from Instituto Health Sciences Career Academy, developed their far-ranging number “Yorktown” from the saga of the last major land battle of the Revolutionary War. And Carmen Villagomez, from Epic Academy Charter High School, took her cue from Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” which he addressed to King George about his treatment of British citizens in America as second-class citizens. She said that what Thomas Paine did was very brave: “It would be like me talking to Donald Trump. It’s the first song I ever made; funny how I made it out of history.”

Lyricist Cynthia Moreno and guitarist Jesus Martinez, from Instituto Health Sciences Career Academy, developed their far-ranging number “Yorktown” from the saga of the last major land battle of the Revolutionary War. And Carmen Villagomez, from Epic Academy Charter High School, took her cue from Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” which he addressed to King George about his treatment of British citizens in America as second-class citizens. She said that what Thomas Paine did was very brave: “It would be like me talking to Donald Trump. It’s the first song I ever made; funny how I made it out of history.”

And Julia White and Jocelyn Santos, from Pritzker College Prep, delivered “We Are The People” as a smart argument between two women, one British and the other American, who will never see eye to eye, with one demanding loyalty and the other claiming “You don’t have a clue because you don’t walk in my left or right shoe.” It ends with their views apart — “We are united not divided.” “We are divided not united.” — and it brought the house down.

The students’ show was followed by a riveting Q&A session from the lip of the stage with Cervantes, Kirkland, dancer Samantha Pollino, and Candace Quarrels, who performs in the ensemble and is prepared to substitute for any of the actors playing the trio of Schuyler sisters, one of whom marries Hamilton. The questions inspired frank talk among the professionals about the reality of type-casting among people of color – and how that might be changing for the better, thanks in part to the example of “Hamilton.”

“It’s pretty amazing what is happening,” Cervantes said, “especially in ‘Hamilton’ but also in the entertainment industry in general. There’s an awareness that this person doesn’t have to be a certain color or race to play a role. I’m a guy named Miguel and I go in to these auditions and they’re often going to be for roles like Carlos or Juan or a drug dealer or a gangster. And you want to do a good job — but you also want to go for ‘LIKE’ [as in likable roles.] “You also want to go in for the doctor, you know what I mean? And it feels like that is happening. But, little by little, right?”

A question that got everybody on the panel thinking was what character they’d like to talk to, if they could go back in history. Without a doubt, said Kirkland, it would be George Washington, the character he plays: “I mean he had all of this respect globally. I think it was Angelica Schuyler who wrote ‘I’ve met dignitaries and kings and all that, but they pale in comparison to George Washington.’ I’d love to ask him if he knew he was that big a deal, because you know if you meet celebrities and star athletes today, these are just people living their lives.

“And then on the flip side, I would love to have that slavery conversation with him. Because internally I believe he knew that slavery was an issue, because apparently he freed his slaves upon his death, which to me was the coward’s way out. I would love ask him why, if he had the courage to start a nation, and if he had the courage to fight a war, he could not stand behind his convictions and free these human beings that are building this nation? But I guess a lot of those guys treated slavery the way we treat concussions in football, like they knew it was terrible but the product is so good they’re not going to say anything.”

“And then on the flip side, I would love to have that slavery conversation with him. Because internally I believe he knew that slavery was an issue, because apparently he freed his slaves upon his death, which to me was the coward’s way out. I would love ask him why, if he had the courage to start a nation, and if he had the courage to fight a war, he could not stand behind his convictions and free these human beings that are building this nation? But I guess a lot of those guys treated slavery the way we treat concussions in football, like they knew it was terrible but the product is so good they’re not going to say anything.”

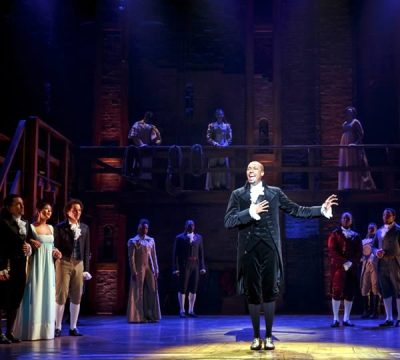

Obviously there was a lot to chew on over sack lunches in the ballroom at the Palmer House Hilton, where the students rested before going back to the theater for a knockout performance of the full show featuring the same cast the students had already met. The story follows the rise of revolutionaries inspired by Hamilton, who is determined to “take his shot” in a new country, while the more cautious Burr – whose fight for a place of power (“I wanna be in the room where it happens”) is often thwarted by Hamilton – becomes his devious and bitter rival. King George is hilariously mocked – “You’ll be back, just you wait” – and dancers are onstage almost nonstop in fast-moving scenes that bring the brash young era to life.

The laughs didn’t always come in the same places they do with adults in the audience, but as tension built toward the duel that ends in Hamilton’s death, the crowd was rapt, and the cheers at the end of the show split the ears in joyful riot. In truth, how can an actor not love a crowd like this, with past, present and future all alive in the hall? “Hamilton’s” score is itself a generational blend of hip-hop, jazz, blues, rap, R&B and Broadway – a 250-year-old tale told in the cultural now.

“Hamilton’s” educational program runs like a well-oiled machine these days. The show’s producer, Jeffrey Seller, first devised it in New York with Miranda, the Rockefeller Foundation, the NYC Department of Education and the Gilder Lehrman Institute, whose president, James G. Basker, pronounced it “transformative” for the way it helped students to experience American history and to “find their own connections to the Founding Fathers, to the performing arts, and to the future of our country.”

Local funders of the “Hamilton” Education Program in Chicago include the Crown and Goodman Family, Ken Griffin, the Joyce Foundation, the Polk Brothers Foundation, the Pritzker Foundation, the Pritzker Traubert Family Foundation, and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.