Postmortem opera: ‘Charlie Parker’s Yardbird’ catches bop star musing on life – after death

Review: “Charlie Parker’s Yardbird.” Music by Daniel Schnyder, libretto by Bridgette A. Wimberly. Produced by Lyric Opera of Chicago at Harris Theater, through March 26. ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

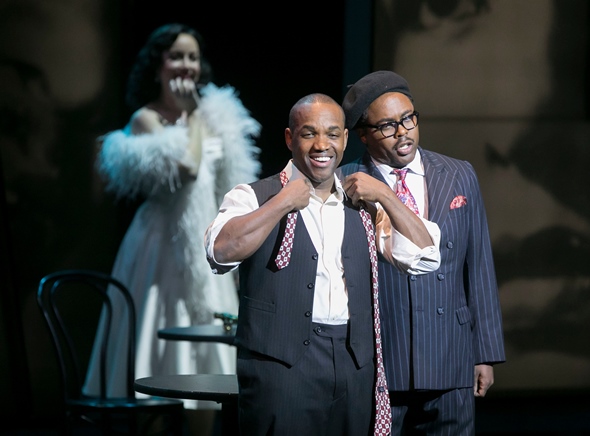

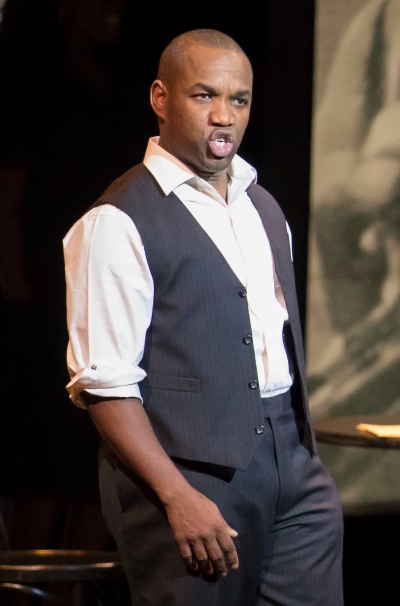

I can only assume that tenor Lawrence Brownlee’s next operatic role will be Muhammad Ali. It took Brownlee all of five minutes as legendary jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker to own that tragic character – to reveal a deeply flawed figure as one who was determined to be his own man, a brilliant, scarred fighter who proved to the world that he was the greatest.

The vehicle for Brownlee’s prodigious and indeed compelling display was “Charlie Parker’s Yardbird,” a fiercely concentrated opera by Daniel Schnyder with a libretto by Bridgette A. Wimberly that opened a too-brief run March 24 at the Harris Theater under the aegis of Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Lyric Unlimited community outreach program. The 90-minute, chamber-scaled work had its premiere in 2015 at Opera Philadelphia. Here, the second and last performance is March 26.

Parker, who emerged from Kansas City to dazzle the jazz world at the cutting edge of bebop, died of a heart attack in 1955 at age 34 after years of substance abuse as diverse as it was relentless. He went out the way he had lived, dying in the New York hotel suite of a French-born socialite and thereby setting off a juicy scandal.

Parker, who emerged from Kansas City to dazzle the jazz world at the cutting edge of bebop, died of a heart attack in 1955 at age 34 after years of substance abuse as diverse as it was relentless. He went out the way he had lived, dying in the New York hotel suite of a French-born socialite and thereby setting off a juicy scandal.

In fact, a few days passed before Parker’s body was correctly identified and the time and circumstances of his death were confirmed. It’s in that time-lapse that the opera’s fictional story unfolds, as Parker’s ghost races to compose something grand and lasting before he is (literally) spirited off to One Place or the Other.

So where else should this man, known throughout the jazz world as Bird, hunker down to create his masterpiece but Birdland, the New York jazz emporium named for him – evoked by set designer Riccardo Hernandez in suspended images of jazz greats.

But in a reversal of the usual way these things go, the ghost is haunted by the living – his three wives (the last one common-law), his doting mother and no less a fellow bop giant than Dizzy Gillespie. In essence, Bird’s timeout to create something monumental turns into a supercharged recap of his life: a memory play.

Wimberly’s libretto is raw, taut and incisive; Schnyder’s musical score by turns bluesy, romantic and brash. But end to end, this work of white-hot theater centers on Bird, its effect dependent on an almost Herculean vocal performance; and in Brownlee’s galvanic effort, it gets nothing less.

Wimberly’s libretto is raw, taut and incisive; Schnyder’s musical score by turns bluesy, romantic and brash. But end to end, this work of white-hot theater centers on Bird, its effect dependent on an almost Herculean vocal performance; and in Brownlee’s galvanic effort, it gets nothing less.

The fraught course of Bird’s life echoes in the voices of five women who knew him best: his mother Addie (the magnificently soulful and suffering Angela Brown), the devoted Baroness Nica (sung with compassion and luscious beauty by mezzo-soprano Julie Miller) and the three “wives,” the last and ultimately closest of whom was Chan Parker, a white woman who took his name though they were not officially married. Soprano Rachel Sterrenberg brought to Chan an infectious presence and vocal exuberance that lit up the house. You couldn’t help thinking, no wonder he was drawn to her.

Adroitly fleshing out Bird’s marriages that didn’t last were mezzo-soprano Krysty Swann as Rebecca Parker and soprano Angela Mortellaro as Doris Parker. (Costumer Emily Rebholz gives all the Bird-women a high-styled look.)

Bopping and bobbing with the crazy currents of Bird’s life was Diz, the good counselor who could not get through to the headstrong sax star. Urge Bird as he might to cut out the drugs, Diz (in the warm voice and cool figure of baritone Will Liverman) never gets through to his friend. Bird’s in high gear on his race to oblivion, and neither love nor reason is going to stop him.

Bopping and bobbing with the crazy currents of Bird’s life was Diz, the good counselor who could not get through to the headstrong sax star. Urge Bird as he might to cut out the drugs, Diz (in the warm voice and cool figure of baritone Will Liverman) never gets through to his friend. Bird’s in high gear on his race to oblivion, and neither love nor reason is going to stop him.

Yet there is grace in this tragedy – grace in the sound of Bird’s inimitable horn reflected through the prism of a 16-piece orchestra under the fluent leadership of Kelly Kuo.

In the end, it is Bird who finds his own meaning, his own redemption – not in a new musical creation, but in the sum of his life’s work. Librettist Wimberly gives him verses from the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “Sympathy,” which begins with the ringing line, “I know what the caged bird feels, alas,” and ends with the poignancy of “I know why the caged bird sings.” It is knowledge of oneself, the key to a cosmic mystery, the driving force behind a musician called Bird.

Related Link:

- Performance and ticket info: Details at HarrisTheaterChicago.org