On a medieval adventure, Newberry Consort explores music of a soldier-poet-composer

Review: A diverse and surprising program was devoted to the obscure music of 15th-century Austrian Oswald von Wolkenstein.

By Kyle MacMillan

While some unexplored or at least under-explored crannies of Baroque, Romantic or even modern composition can still be found, the music of the Middle Ages remains filled with buried treasure. For a set of concerts that ran Jan. 13-15, the ever-intrepid, ever-imaginative Newberry Consort delved into this rich period and hit pay dirt with a transporting and absorbing program devoted entirely to the little-known music of Oswald von Wolkenstein.

An Austrian soldier, nobleman, diplomat, traveler and avid lover, Oswald (1376-1445) led a fascinating, globetrotting life filled with adventures and misadventures, including imprisonment and even a shipwreck. On top of everything else, he was a gifted poet and composer who wrote forward-looking music that provided a bridge to the subsequent Renaissance era. The Newberry Consort’s artistic leaders pored through more than 130 of his songs, many of which Oswald preserved in two manuscripts, and selected 14 of them for this offering.

An Austrian soldier, nobleman, diplomat, traveler and avid lover, Oswald (1376-1445) led a fascinating, globetrotting life filled with adventures and misadventures, including imprisonment and even a shipwreck. On top of everything else, he was a gifted poet and composer who wrote forward-looking music that provided a bridge to the subsequent Renaissance era. The Newberry Consort’s artistic leaders pored through more than 130 of his songs, many of which Oswald preserved in two manuscripts, and selected 14 of them for this offering.

Outside of some religious odes, such as “Ave Müter Königinne (Hail Queen Mother),” which ended the program, nearly everything that Oswald wrote had an autobiographical bent. That was especially true of the opening song, “Es fügt sich, da ich was von zehen jaren alt,” which began fittingly with these words, “When I was 10 years old, I decided I wanted to see the world.” The five verses of that lively musical chronicle were spread across the two halves of the program and provided a helpful narrative structure for the evening.

Famed countertenor Drew Minter is clearly well versed in the vocal style of this era, and he brought a relaxed eloquence and storyteller’s flair to the extended tale, suffusing it with a touching empathy for Oswald’s pains and fears as the composer grows old. One of six singers and musicians featured on the program, Minter was a founding member of the Newberry Consort who returned to take part in these concerts.

Oswald’s songs manage to be both simple and sophisticated, with a lightness, plain-spokenness and humor about them. They carry us back to a long-ago time, but also come off as surprisingly fresh and relatable, especially the unabashed eroticism of some of the romantic songs that seems downright contemporary.

Oswald’s songs manage to be both simple and sophisticated, with a lightness, plain-spokenness and humor about them. They carry us back to a long-ago time, but also come off as surprisingly fresh and relatable, especially the unabashed eroticism of some of the romantic songs that seems downright contemporary.

While he wrote some of his music in a monophonic style, other works are polyphonic with sometimes surprising dissonances. In his program notes, co-director David Douglass even uses the term “tone clusters” to describe the unexpected clashing harmonies in “Frölich geschrai so well wir machen, lachen,” a delightfully witty and saucy love song that drew multiple laughs. While nearly all of the evening’s selections were songs, the program included two instrumental works, including the captivating “Wolauff gesell,” with some of the program’s most complex harmonies.

Among the concert’s other high points was “In Frankenreich (In France),” a gentle love song. Consort co-director Ellen Hargis has an obvious affinity for early music of this kind, and she graced the lyrics with a floating line and nuanced delicacy. Also noteworthy were the high-spirited “Nu Huss!” with its catchy rhythmic cadence; “Simm Gredlin, Gret mein Gredelein,” another erotic song strikingly rendered by the well-matched Minter and Hargis, and “Komm, liebster Mann,” a round featuring Hargis and Debra Nagy, the concert’s third vocalist.

Each of the six singers and musicians wore more than one hat during the concert, with Minter, for example, also performing on harp and drums at times. The most compelling of the instrumentalists was Mary Springfels, the Newberry’s founding artistic director who left the group in 2007 but was back for this distinctive program. She split her time between the citole, a guitar-like instrument with a slightly more restrained but no less fetching sound, and the vielle. Springfels held the latter between her legs and played it like a cello, and it had a similarly burnished, amber sound.

Each of the six singers and musicians wore more than one hat during the concert, with Minter, for example, also performing on harp and drums at times. The most compelling of the instrumentalists was Mary Springfels, the Newberry’s founding artistic director who left the group in 2007 but was back for this distinctive program. She split her time between the citole, a guitar-like instrument with a slightly more restrained but no less fetching sound, and the vielle. Springfels held the latter between her legs and played it like a cello, and it had a similarly burnished, amber sound.

Perhaps most versatile was Nagy, who contributed vocals on a few songs and played harp as well as recorder and an early oboe. Also taking part were Douglass and Allison Monroe, a doctoral student in historical performance practice at Case Western Reserve University, who switched between a viola-like version of the vielle and the narrower, violin-like rebec. (It would have been helpful if the program or pre-concert lecture would have provided some background on these instruments, which are hardly familiar to most listeners.)

The concert reviewed here was given Saturday evening in the 474-seat Performance Hall at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts. The venue could hardly have been more ideal both in terms of its physical intimacy and acoustics, which are clear and accommodating without being too bright or reverberent.

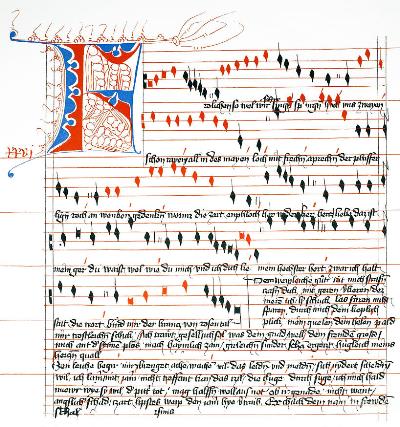

As is typical with the Consort’s offerings, the program was accompanied by a slideshow that provided not only the English translations of the texts of the songs but also visual imagery drawn from maps and illuminated books and manuscripts of the period, including those containing Oswald’s songs. All that was missing were the German titles of the selections, so that the audience could easily follow along in the printed program.

The projections were rigorously researched and tastefully assembled by Shawn Keener, a musicologist who works as an editor at A-R Editions, a publisher of scholarly editions of music. The images blended together in a subtle, non-distracting way. Purists would likely argue that the music could stand on its own and does not need any visual aids, and that is certainly a valid point of view. But a strong argument can also be made that the visuals helped take listeners back in time, conjure Oswald’s multifaceted world and set the scene for his evocative songs.