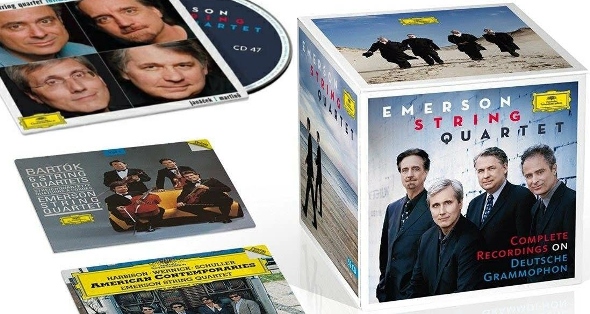

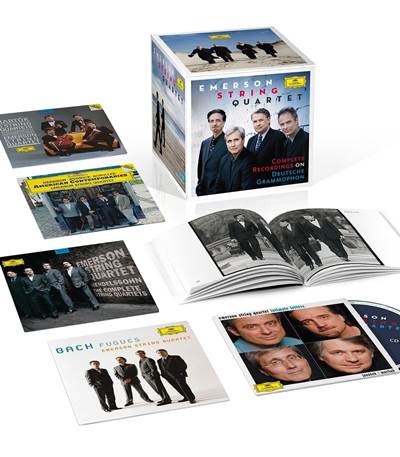

Forty years and 52 discs in a treasure box: Emerson Quartet’s prodigious history, redux

Review: Deutsche Grammophon’s anniversary retrospective bundles its entire vault of recordings by a benchmark ensemble.

Review: Deutsche Grammophon’s anniversary retrospective bundles its entire vault of recordings by a benchmark ensemble.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

In 1988, the already well-established and widely praised Emerson String Quartet recorded the six string quartets of Béla Bartók. It was upon hearing those revelatory recordings that I promoted the Emerson to the top spot in my own mental ranking. Even measured against a stellar field, this was surely the greatest string quartet in the world.

Nearly three decades later, in observance of the Emerson’s 40th anniversary, Deutsche Grammophon has issued a 52-CD retrospective of the quartet’s entire output on the label. It’s an astounding tour – indeed a tour de force – that confirms again and again the virtuosity, elegance, potency and range of a foursome that seems to embrace the entire quartet canon with the same singular breathtaking ease and penetrating insight.

As part of its celebratory concert trek this season, the Emerson comes to the Harris Theater on Oct. 19. The program includes Beethoven’s String Quartet in F minor, Op. 95, the Bartók Fourth and Mendelssohn’s Octet for Strings with members of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.

As part of its celebratory concert trek this season, the Emerson comes to the Harris Theater on Oct. 19. The program includes Beethoven’s String Quartet in F minor, Op. 95, the Bartók Fourth and Mendelssohn’s Octet for Strings with members of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.

Not the least remarkable feature of the Emerson’s long history is the stability of its membership. Founded by violinists Eugene Drucker and Philip Setzer as a student ensemble at the Juilliard School, the quartet turned professional in 1976. After a couple of early personnel changes, the foursome was solidified with the additions of violist Lawrence Dutton and cellist David Finckel. It would remain unchanged for 34 years, until Finckel left in 2013, to be replaced by Paul Watkins.

And from the beginning in their student days, violinists Drucker and Setzer have routinely alternated as first and second, a practice they began as a learning technique, then continued for the benefits of flexibility and freshness they derived from the constant changing of demands and perspective.

The discs in this box essentially encompass the entire performed string quartet repertoire, and then some. All of Beethoven is here, all of Shostakovich, Brahms, Bartók, Mendelssohn (a discovery in itself), the mature Dvořák (more than just string quartets) and Schubert, a very clever connect-the-stylistic-dots overview of Haydn, and the six magnificent quartets Mozart dedicated to Haydn – which is where I jumped into this broad stream.

It was right after their Bartok cycle that the Emerson recorded Mozart’s so-called “Haydn” Quartets, between 1988 and 1991. Talk about a testament of range: The precision of those Bartok performance translates into the ethereal finesse of the Emerson’s Mozart. This is burnished Mozart – the rhythm buoyant and animated, the sound luminous and transparent.

It was right after their Bartok cycle that the Emerson recorded Mozart’s so-called “Haydn” Quartets, between 1988 and 1991. Talk about a testament of range: The precision of those Bartok performance translates into the ethereal finesse of the Emerson’s Mozart. This is burnished Mozart – the rhythm buoyant and animated, the sound luminous and transparent.

Over the four decades of the Emerson’s recording history, which happens to line up almost exactly with my career as a critic, I have reviewed much of the contents of this prodigious box. I was already familiar with the quartet’s visceral and probing Beethoven, from the three watershed masterpieces of Op. 59 to the transcendent late quartets. What I did not specifically recall was the Emerson’s vibrant account of Beethoven’s first ventures in the form, the six already idiosyncratic, even brash quartets of Op. 18. These arresting performances are among many such treasurable discoveries awaiting here.

I wonder how many chamber music aficionados can claim familiarity with the Mendelssohn string quartets, a bountiful arc that stretches from the composer’s youth to his prime, filling four full discs. Likewise, while Dvořák’s “American” Quartet in F major is standard, who knows his other mature quartets? They are here, luxurious Romantic essays that draw you immediately back for another hearing. To which is added the special treat of “Cypresses,” an arrangement of a shadowy song cycle by the young Dvořák.

One does run out of encomiums for the Emerson and its splendorous legacy; and then, pulling disc after marvelous disc from this chest of wonders, one comes upon the complete Shostakovich – the whole staggering sequence of 15 string quartets, that most intimate profile of a towering composer. As no amount of verbiage will suffice, let us call it, in one word, monumental. Like its Beethoven, the Emerson’s Shostakovich bespeaks, beneath the musical surfaces, an intellectual depth of thrilling profundity.

One does run out of encomiums for the Emerson and its splendorous legacy; and then, pulling disc after marvelous disc from this chest of wonders, one comes upon the complete Shostakovich – the whole staggering sequence of 15 string quartets, that most intimate profile of a towering composer. As no amount of verbiage will suffice, let us call it, in one word, monumental. Like its Beethoven, the Emerson’s Shostakovich bespeaks, beneath the musical surfaces, an intellectual depth of thrilling profundity.

I keep circling back to the leitmotif of stylistic range. For the Emerson, it’s all music, all poetry, whatever the harmonic language, the meter, the rhyme scheme. Witness further, on the one hand, the Romantic heat and arching lyricism of its Schubert and Schumann, and on the other hand the stark aphorisms of Webern and the distilled expressionism of Berg.

Yet for me the really unexpected delight, something I’d overlooked back in the day, is a two-fold excursion into Bach, who of course wrote no string quartets. On separate discs, the Emerson explores fugues arranged from Bach’s “The Well-Tempered Clavier” and offers a sublime traversal of “The Art of Fugue.”

There’s a great deal more, from Prokofiev and Janáček and Ives to the indispensable quartets of Debussy and Ravel, and a 140-page booklet provides detailed information on the collection’s contents and recording dates. The musical riches bundled here are synonymous with the scope and import of the Emerson Quartet: immeasurable.