English kings in bloody struggles for power: Part 2 of Chicago Shakespeare’s history saga

Review: “Tug of War: Civil Strife,” based on Shakespeare’s history plays, at Chicago Shakespeare Theater through Oct. 9 ★★★★

Review: “Tug of War: Civil Strife,” based on Shakespeare’s history plays, at Chicago Shakespeare Theater through Oct. 9 ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s outsized and smartly honed two-part miniseries “Tug of War,” focusing on the endless cycle of royal usurpation and bloodshed in the Bard’s history plays, comes to its conclusion with a sequence that illuminates the brief reign and unsurprising death of horseless Richard III at Bosworth Field.

For my part, I shall not ask with the great songstress Peggy Lee, “Is that all there is?” My question is: When will we be able see it again?

We should all play courtiers and make a deep bow to CST artistic director Barbara Gaines, who distilled and directed the six plays that form this clever and clarifying project. The profusion – and, let us admit it – confusion of dukes and clerics and queens (some only for a day) doubtless work against appreciation of the history plays, at least on this side of the pond.

We should all play courtiers and make a deep bow to CST artistic director Barbara Gaines, who distilled and directed the six plays that form this clever and clarifying project. The profusion – and, let us admit it – confusion of dukes and clerics and queens (some only for a day) doubtless work against appreciation of the history plays, at least on this side of the pond.

Hence, as much as anything, Gaines’ ambitious venture – each of the two parts creating a continuum through the events and personas of three plays – has reinforced both historical and dramatic context in Shakespeare’s prodigious arc extending from Kings Edward III and Henry V to Henry VI and that misshapen serpent and stage favorite Richard III.

The first part of “Tug of War,” presented at the end of last season under the general header “Foreign Fire,” dealt largely with the English crown’s thinly justified, empire-building military ventures in France. Perhaps the most vivid takeaway from that immersion was a powerful case for including “Edward III” in the Shakespeare canon, under the same co-authorship long since granted to “Timon of Athens,” “Pericles,” “Two Noble Kinsmen” and “Henry VIII.” I for one would like to see CST revisit “Edward III” in a full-scale production.

This six-hour follow-up, titled “Civil Strife,” commences where “Foreign Fire” left off, in the reign of Henry VI, an acorn that indeed fell far from the mighty oak, his father Henry V. The younger Henry, in Shakespeare’s telling, is a feckless man and timorous king, easily intimidated by other claimants to his crown, more disposed to meditation and prayer than to confrontation. The most threatening wolf at Henry’s door is the Duke of York, who simply bullies Henry off the throne and into immured retirement – in the Tower.

This six-hour follow-up, titled “Civil Strife,” commences where “Foreign Fire” left off, in the reign of Henry VI, an acorn that indeed fell far from the mighty oak, his father Henry V. The younger Henry, in Shakespeare’s telling, is a feckless man and timorous king, easily intimidated by other claimants to his crown, more disposed to meditation and prayer than to confrontation. The most threatening wolf at Henry’s door is the Duke of York, who simply bullies Henry off the throne and into immured retirement – in the Tower.

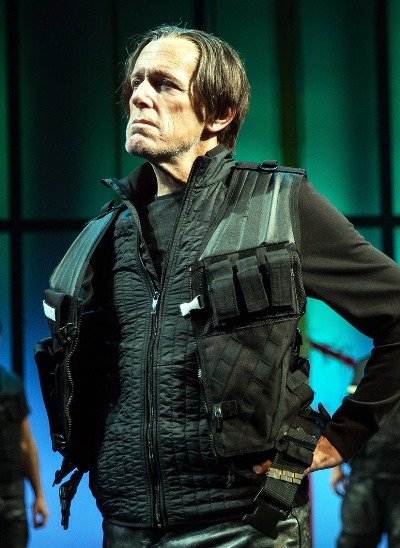

And in these two opposites we find the true co-stars of Gaines’ sequel. Against Steven Sutcliffe’s sharply drawn Henry, who sighs and minces and despairs of the world’s weight, Larry Yando brings a brash, calculating, fearsome and resolute York, a warrior who wills himself to the throne – even if not for very long.

Essential to both of these fine performances is the two actors’ shared consciousness of Shakespeare’s language, its precision and nuance and pulse. No matter the level of emotional intensity, Sutcliffe and Yando allow the language to express the moment. Which brings me to the character we’re all there ultimately to see, to delight in, to hiss at: Richard III.

In the story of Henry VI, young Richard is mainly in the background. He is one of York’s four sons. One of them finds an early, violent death. The eldest, Edward, seizes the throne when his father loses it; an attempt by Henry to regain power is quickly thwarted. As we move — in a mere scene change here — from “Henry VI,” Parts 2 and 3, to “Richard III,” we immediately encounter the bitter, malformed, misanthropic Richard, brimming over with spleen and envy: “Now,” he chirps with venomous irony, “is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this son of York.” It is his own brother whom he marks in this baleful speech.

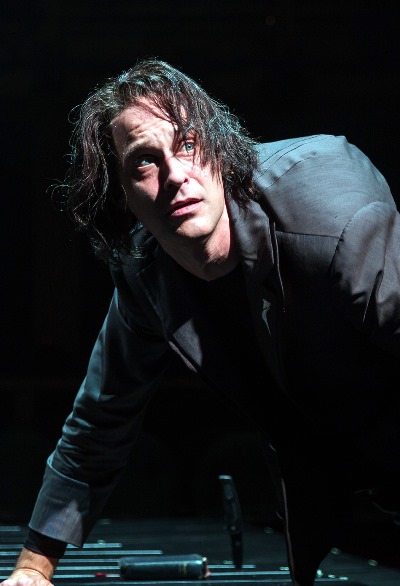

Thus Timothy Edward Kane steps fully into the weeds and will of Richard. It is a mixed impersonation. In every respect, Kane looks the part: Attired in black, he moves with the slithering indirection of a snake, his left side damaged from birth, shoulder humped, withered arm and leg drawn in like the damaged appendages of some foul spider. You can’t take your eyes off him.

Thus Timothy Edward Kane steps fully into the weeds and will of Richard. It is a mixed impersonation. In every respect, Kane looks the part: Attired in black, he moves with the slithering indirection of a snake, his left side damaged from birth, shoulder humped, withered arm and leg drawn in like the damaged appendages of some foul spider. You can’t take your eyes off him.

But starting with that wry speech on happy summer, Kane plows over and through Shakespeare’s metered, coiled and freighted lines. The actor mistakes speed for intensity; perhaps he means his tumbling expostulations to signify incipient madness. But he is merely hard to understand. All that is fraught in Richard’s mind resides in his words. Warp-speed delivery renders this maleficent soul less insidious, not more so. Where was Gaines’ measuring hand?

With this bizarre exception, the large cast of players – most of them in multiple roles — treats Shakespeare’s language clearly and knowingly. Karen Aldridge as Queen Margaret, wife to Henry VI, conveys the lady’s royal contempt for her husband as well as her tormented passion for one of his courtiers. Elizabeth Ledo is a multi-faceted delight in several spunky trouser roles, and Heidi Kettenring offers a radiant presence as Queen Elizabeth, the beautiful widowed commoner elevated to throne and royal bed by Edward IV (Michael Aaron Linder as the swaggering, impetuous monarch).

But Kevin Gudahl, like a briefly seated king, for a moment wore this marathon’s coronet as the populist politico and rabble-rouser Jack Cade. Appearing dandified in a suit with artfully coiffed, almost-orange-blond hair, this fast talker with big ideas and no grasp of practical reality – we’ll kill all the lawyers, everyone will have plenty of money, no schools, follow me – drew howls of seeming recognition from the audience. I can’t imagine what familiar face was perceived in Gudahl’s grinning portrayal of Shakespeare’s inflated, unlettered, reckless charlatan.

But Kevin Gudahl, like a briefly seated king, for a moment wore this marathon’s coronet as the populist politico and rabble-rouser Jack Cade. Appearing dandified in a suit with artfully coiffed, almost-orange-blond hair, this fast talker with big ideas and no grasp of practical reality – we’ll kill all the lawyers, everyone will have plenty of money, no schools, follow me – drew howls of seeming recognition from the audience. I can’t imagine what familiar face was perceived in Gudahl’s grinning portrayal of Shakespeare’s inflated, unlettered, reckless charlatan.

The whole enterprise, here as in the earlier saga, is consolidated and strengthened by the technical elements of scenic design (Scott Davis), costumes (Susan E. Mickey) and lighting (Aaron Spivey). Common to both segments, as well, is the interpolation of song – or rather something closer to musical aphorisms, little sung codas that frequently cap off scenes of varying dramatic import. Music had a central place in Shakespeare’s plays, yet these modern lyric flourishes generally suggested to me that Gaines didn’t trust the text. Flinty York bursting into song was the nadir – the ultimate sign of winter’s discontent.

Still, distracting as they may be, these emotive punctuations, backed by electric guitars, are hardly fatal. Nor do Gaines’ necessary excisions cut the hearts from the three plays in view. This is indeed Shakespeare with asterisks, semi-Shakespeare, but what is preserved is substantial, integrated and authentic. It’s a rare opportunity to catch the history plays in the full frame of continuity. On balance, it is also excellent work.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s complete 30th-anniversary season: Details at ChicagoShakes.com

Tags: Barbara Gaines, Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Elizabeth Ledo, Heidi Kettenring, Karen Aldridge, Kevin Gudahl, Larry Yando, Michael Aaron Linder, Steven Sutcliffe, Timothy Edward Kane, William Shakespeare