‘Beast on the Moon’ at Raven: After Armenian genocide, an improbable pair retool their lives

“Beast on the Moon” by Richard Kalinoski, at Raven Theatre through June 6. ★★★★

“Beast on the Moon” by Richard Kalinoski, at Raven Theatre through June 6. ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Outwardly, Richard Kalinoski’s play “Beast on the Moon” is about a young man and a teenage girl, refugees from the 1915 Armenian genocide who have lost their families and embark on a new life together as immigrants in Milwaukee. But as Raven Theatre’s exuberantly funny and sensitive production so urgently telegraphs, this tragi-comedy is ultimately about the beast within – a fearsome creature of the mind spawned by terror, isolation and guilt.

Michael Menendian, Raven’s co-founder and co-artistic director, and scion of Armenians, chose “Beast on the Moon” in observance of the centenary of the Ottoman Empire’s systematic extermination of Christian Armenians. The genocide began in April 1915 and continued through World War I, ending with some 1.5 million Armenians killed. Menendian also directs the play, not only with wit and imagination but also with a palpable spirit of affection.

Michael Menendian, Raven’s co-founder and co-artistic director, and scion of Armenians, chose “Beast on the Moon” in observance of the centenary of the Ottoman Empire’s systematic extermination of Christian Armenians. The genocide began in April 1915 and continued through World War I, ending with some 1.5 million Armenians killed. Menendian also directs the play, not only with wit and imagination but also with a palpable spirit of affection.

Twentysomething Adam Tomasian, recently settled in Milwaukee, has just acquired a mail-order bride called Seta. She is 15 years old and bursting with life. To put it mildly, they’re in for a period of adjustment. For Tomasian, who grew up in a family governed by the old ways, it’s a man’s world in which women speak when they are spoken to. Men do the thinking, women bear the children.

Seta, from a liberal family that encouraged female intellect, finds her new man’s provincial views bizarre, even laughable. She was brought up to embrace life fully, to read and ponder, indeed to laugh. Still, she struggles with the idea of stepping out of girlhood into womanhood, and she clutches a battered doll – all that remains of her shattered past. Tomasian clings to just such a memento of his own: his murdered father’s overcoat, which hid him from the Turks. The coat will bring this fledgling household to a crisis.

As Tomasian and his child bride, Matt Browning and Sophia Menendian make a delightful pair, perfectly mismatched. He is orderly, precise, clear-sighted, determined first and foremost to continue his father’s line. She is big-eyed with wonder at the relative magnificence of her new home, still the rollicking schoolgirl at heart but respectful of her husband’s primacy and eager to please.

As Tomasian and his child bride, Matt Browning and Sophia Menendian make a delightful pair, perfectly mismatched. He is orderly, precise, clear-sighted, determined first and foremost to continue his father’s line. She is big-eyed with wonder at the relative magnificence of her new home, still the rollicking schoolgirl at heart but respectful of her husband’s primacy and eager to please.

The first order of business, Tomasian announces, is to begin procreating. Now. This is sex as serious, purposeful work, with short breathers before plunging back to it. The couple’s dedicated enterprise plays out entirely off-stage. So serious, so driven is Tomasian that when Seta comes home from the doctor with a report that she has not conceived, he drags her off forthwith to try again. Even when Seta is diagnosed as unable to bear children, because of adolescent starvation, Tomasian only redoubles his efforts.

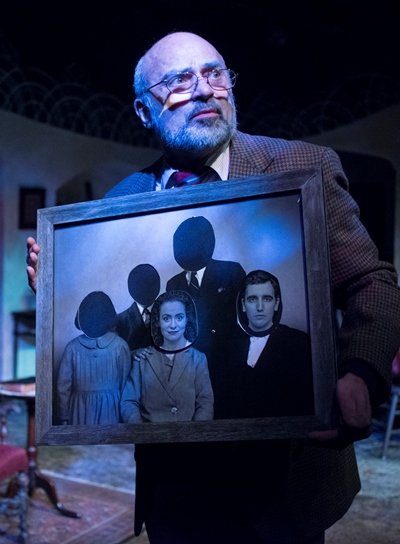

There’s a madness in it, and indeed Tomasian has literally created a frame for his obsession: In an old family portrait, he has lopped off the heads of his dead relatives and replaced the faces of his mother and father with images of himself and Seta. His plan is to re-create his expunged family. A professional photographer, Tomasian documents the arc of his life through pictures: Within that hallowed frame lies a yet-unfulfilled duty to his deceased father.

There’s a madness in it, and indeed Tomasian has literally created a frame for his obsession: In an old family portrait, he has lopped off the heads of his dead relatives and replaced the faces of his mother and father with images of himself and Seta. His plan is to re-create his expunged family. A professional photographer, Tomasian documents the arc of his life through pictures: Within that hallowed frame lies a yet-unfulfilled duty to his deceased father.

While the play appears to be Tomasian’s story, and Browning imbues the man with credible passion as well as genuine decency, it is Seta’s adjustment, maturation (over a 12-year period) and compassionate partnership that more compellingly draw us in. Sophia Menendian’s warm, nuanced, fiercely clear-eyed performance gives the production wings. It is prodigiously accomplished work by an actress, the director’s daughter, who is still a student at the University of Illinois – Chicago.

Quite remarkable as well is the very young Aaron Lamm, as the street urchin Vincent, whom Seta takes under her wing – initially unbeknownst to Tomasian. Some of the show’s best comedy springs from Tomasian’s shocked discovery of this kid in their home and Lamm’s off-hand street-smart cockiness.

The play also involves a fourth persona, called simply a Gentleman, a fellow of advanced years who moves things along as narrator, sits in as silent observer and occasionally hands out props. I shall not tell you more about him, except that Ron Quade meets those tasks with an appealing aura of wisdom.

The play also involves a fourth persona, called simply a Gentleman, a fellow of advanced years who moves things along as narrator, sits in as silent observer and occasionally hands out props. I shall not tell you more about him, except that Ron Quade meets those tasks with an appealing aura of wisdom.

Designer Kristin Abhalter’s homey set is nicely complemented by Lauren Roark’s costumes, both strikingly accentuated by lighting designer Diane D. Fairchild.

Especially notable are Kelly Rickert’s set-up projections, a prelude of historic images of Armenians in the homeland – happy, ordinary, beautiful people suddenly twisted into the damned, crucified along roadways and herded into oblivion. Such is the common provenance of Tomasian and Seta, the awful history they transcend together.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: Aaron Lamm, Diane D. Fairchild, Kelly Rickert, Kristin Abhalter, Lauren Roark, Matt Browning, Michael Menendian, Raven Theatre, Richard Kalinoski, Ron Quade, Sophia Menendian