Chicago Opera Theater buffs up neglected jewel in high-tech staging of Bloch’s grand ‘Macbeth’

Review: “Macbeth” by Ernest Bloch, with baritone Nmon Ford and soprano Suzan Hanson, at Chicago Opera Theater through Sept. 21. ★★★

By Nancy Malitz

When Verdi unveiled his opera “Macbeth,” based on the Shakespeare tragedy, he was 33, a seasoned professional with 10 premieres under his belt and his biggest hits, starting with “Rigoletto,” just around the corner. Verdi confidently distilled Shakespeare’s structure in the interest of his lyric theater instincts, replacing the three witches with a covenly chorus and shining the spotlight on Macbeth’s ruthlessly ambitious wife. Her extended sleepwalking scene is a diva’s diamond standard.

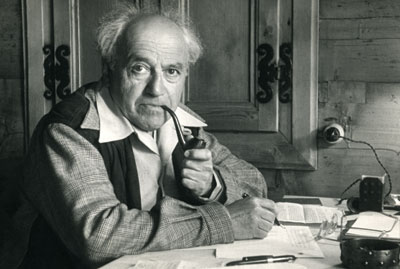

When Swiss-born Ernest Bloch began to contemplate his first and only opera, “Macbeth,” he was an untested 25 and would spend years at the task. Bloch was 30 when his opus at last found footing at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. Given Bloch’s relative inexperience, it is hardly surprising that he was almost religiously faithful to Shakespeare’s structure, and that he retained the Bard’s emphasis on the Scottish king’s bloodthirsty transformation, as opposed to the queen’s unraveling.

When Swiss-born Ernest Bloch began to contemplate his first and only opera, “Macbeth,” he was an untested 25 and would spend years at the task. Bloch was 30 when his opus at last found footing at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. Given Bloch’s relative inexperience, it is hardly surprising that he was almost religiously faithful to Shakespeare’s structure, and that he retained the Bard’s emphasis on the Scottish king’s bloodthirsty transformation, as opposed to the queen’s unraveling.

What is surprising is how staggeringly good Bloch’s result is, for an opera that almost no one knows.

As a Jew, Bloch survived two world wars and the holocaust by virtue of his Swiss citizenship, which eventually led to safe harbor and stability on America’s west coast. Long before that, U.S. orchestras had taken up his cause. Back in 1932, Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra offered the world premiere of “Helvetia,” Bloch’s lovely symphonic ode to his Swiss homeland. And in 1953, Chicago Symphony principal violist Milton Preves and music director Rafael Kubelik ushered his “Suite Hébraïque,” for viola and orchestra, into the world. But performances of Bloch’s music, along with much other mid-century fare, diminished in ensuing decades.

Bloch’s under-performed “Macbeth” stands among his neglected jewels. Surely baritones will appreciate that in this “other Macbeth” it’s the king who gets the diamond standard aria, a harrowing musical setting of “She should have died hereafter … tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,” following the death of the queen. It comes at the dramatic climax of the opera, with the king’s precipitous fall from the height of evil magnificence to miserable dusty death underway. The impact of this scene was still ringing in my ears long after the curtain fell at Chicago Opera Theater.

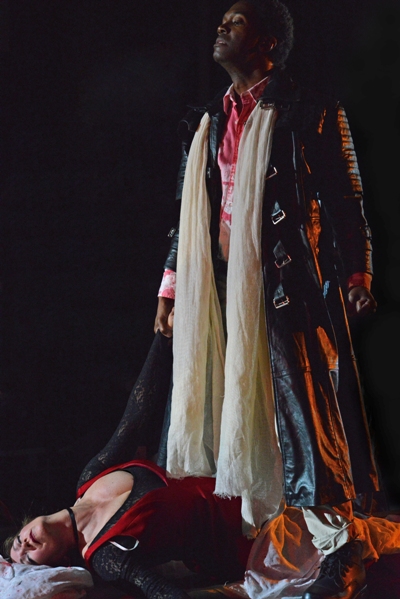

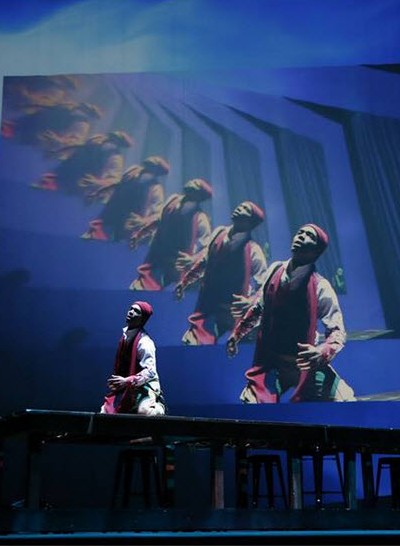

Bloch’s “Macbeth” is a massive, sprawling thing. Credit is due this ambitious company for giving us a decent glimpse of it, under the leadership of conductor Francesco Milioto and stage director Andreas Mitisek (who is also COT’s general director). The opera is sung in English, a version that Bloch helped to develop for a mid-century performance directed by John Houseman at the Juilliard School. It’s a rather lean but intense affair, starring baritone Nmon Ford and dramatic soprano Suzan Hanson as youthful king and queen, with a pared-down cast, a modest orchestra thirsty for a few more strings, an able but lamentably offstage chorus, and a score with substantial trims — the whole buttressed by some sensational lighting and video touches (David Bradke and Sean T. Cawelti), three quite charming witches from COT’s young artist program, and solid musical values throughout.

If as a production it had the occasional feel of a big party room with too few people in it, Ford and Hanson were riveting at the core. And I for one was grateful to hear a major opera by a visionary 20th-century composer with roots in the 19th, who is unfairly remembered these days for just a few works. Bloch is the author of iconic compositions that reflect the Jewish cultural identity: “Schelomo,” a popular Hebraic rhapsody for cello and orchestra; the grand choral-orchestral “Avodath Hakodesh” (Sacred Service); Three Jewish Poems for large orchestra; and “Israel,” a symphony. But as the magisterial sweep of “Macbeth” suggests, there is much more.

If as a production it had the occasional feel of a big party room with too few people in it, Ford and Hanson were riveting at the core. And I for one was grateful to hear a major opera by a visionary 20th-century composer with roots in the 19th, who is unfairly remembered these days for just a few works. Bloch is the author of iconic compositions that reflect the Jewish cultural identity: “Schelomo,” a popular Hebraic rhapsody for cello and orchestra; the grand choral-orchestral “Avodath Hakodesh” (Sacred Service); Three Jewish Poems for large orchestra; and “Israel,” a symphony. But as the magisterial sweep of “Macbeth” suggests, there is much more.

There was a time when Bloch was actually popular. The Metropolitan Opera ignored this one-opera wonder, but the Teatro San Carlo in Naples introduced “Macbeth” in 1938, with plans in the works at other Italian houses, before all got sucked into the advancing Hitler maw. Meanwhile, orchestras in the U.S. were all over Bloch’s music. Karl Muck (Boston Symphony), Arthur Rodziński (New York Philharmonic), Otto Klemperer (Los Angeles Philharmonic), Pierre Monteux (San Francisco Symphony) and Leopold Stokowski (Philadelphia Orchestra) were among those who paid attention and took up his cause.

What happened to Bloch also happened to many other composers of his generation: By the time he was settled in the U.S. after World War II, his own musical language, which was rooted in the grand chromaticism of Wagner and Debussy, and the nationalistic sweep of Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, was falling out of favor. The post-tonal composition strategies of Schoenberg and his followers were taking hold, and held sway, for decades. His style was viewed as yesterday. He saw himself as a composer who perhaps had outlived his time.

What happened to Bloch also happened to many other composers of his generation: By the time he was settled in the U.S. after World War II, his own musical language, which was rooted in the grand chromaticism of Wagner and Debussy, and the nationalistic sweep of Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, was falling out of favor. The post-tonal composition strategies of Schoenberg and his followers were taking hold, and held sway, for decades. His style was viewed as yesterday. He saw himself as a composer who perhaps had outlived his time.

With the loosening of serialism’s grip, tonal palettes are once again embraced. We’re starting to see names like Piston and Sessions and Bax and Hindemith and Milhaud on programs again. Now Bloch as well, thanks in this case to the visionary activism of COT.

Whether “Macbeth” takes a belated place in the present operatic pantheon is an open question. But as a youthful work of undeniable craftsmanship that rises to the level of the finest dramatic and lyric art, this “Macbeth” is a stunning and impressive candidate.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Go to ChicagoOperaTheater.org

- Historic snippet on YouTube: Inge Borkhe sings the sleepwalking scene

Tags: Andreas Mitisek, Chicago Opera Theater, David Bradke, Ernest Bloch, Francesco Milioto, Macbeth, Nmon Ford, Sean T. Cawelti, Suzan Hanson