Chicago Symphony’s new chief is battle tested by long, productive career in orchestra world

Profile: Jeff Alexander, president of the Vancouver Symphony, garners high praise for practicality and vision from Canadian colleagues as well as CSO board chairman; takes Chicago post in January.

By Nancy Malitz

Although the professional classical music world is actually quite small, Jeff Alexander had never met maestro Riccardo Muti before he flew from Vancouver to Chicago for the interviews that led to his appointment as the new president of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association.

Alexander, who becomes administrative chief in January 2015, says he made an inconspicuous visit during the music director’s final week of concerts for the season, in late June. The program consisted of Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 and Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, which Alexander described as “extraordinary, filled with fantastic phrasing and nuance.”

“No, we do not even have mutual friends,” allowed Alexander by telephone shortly after the CSOA named him to the position vacated by Deborah F. Rutter, who stepped down in June after 11 years to assume the leadership of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC. Still, the new president said he and the orchestra’s reigning maestro quickly found common ground.

“No, we do not even have mutual friends,” allowed Alexander by telephone shortly after the CSOA named him to the position vacated by Deborah F. Rutter, who stepped down in June after 11 years to assume the leadership of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC. Still, the new president said he and the orchestra’s reigning maestro quickly found common ground.

“When I mentioned I had worked with Jesús López Cobos at the Cincinnati Symphony, maestro Muti spoke highly of him and told me he had just seen him conduct in Vienna. We had a wonderful chat, a very good meeting, in which we shared a lot of ideas about the music business and about music itself.”

Alexander may seem a low-profile long-shot for those who were handicapping the outcome of the search for one of the top arts executive positions worldwide. But as a closer look at the secret and highly selective search process reveals, Alexander scored high with regard to two attributes deemed paramount: the potential for a simpatico relationship with a brilliant maestro who required passion and knowledge of music first, and a proven track record as the No. 1 decision-maker at a symphony orchestra.

“We placed high priority on significant existing experience in the CEO role for an orchestral organization,” said Jay L. Henderson, the chairman of the board of trustees of the CSOA. Henderson is active on several other Chicago boards, including Rush University Medical Center and the Museum of Science and Industry, and he is vice chairman, client service for PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC. He described a search committee designed to include active participation by board members, musicians and senior staff members who together brought “a cross-section of expertise that proved an important benefit. And with regard to maestro Muti, we wanted to ensure that the candidates had an opportunity to meet with him, and to ensure that the maestro’s input was integrated into our efforts.”

“We placed high priority on significant existing experience in the CEO role for an orchestral organization,” said Jay L. Henderson, the chairman of the board of trustees of the CSOA. Henderson is active on several other Chicago boards, including Rush University Medical Center and the Museum of Science and Industry, and he is vice chairman, client service for PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC. He described a search committee designed to include active participation by board members, musicians and senior staff members who together brought “a cross-section of expertise that proved an important benefit. And with regard to maestro Muti, we wanted to ensure that the candidates had an opportunity to meet with him, and to ensure that the maestro’s input was integrated into our efforts.”

Temperamental clashes at the top have the potential to cause explosive damage, of which the abrupt departure of the conductor and music director Franz Welser-Möst from the Vienna State Opera on Sept. 5 is only the most recent example. Citing irreconcilable differences with artistic director Dominique Meyer, Welser-Möst withdrew from all performances, throwing the current season immediately into disarray, stunning the musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic, who play in the pit, and — not incidentally — leaving one of the most highly coveted conducting jobs in the world unfilled.

In 2005, Muti himself resigned from Milan’s La Scala in a fallout with the staff over programming. There are other destabilizing factors that can occur at any time in an orchestra’s life — bitter contractual disputes, for one, or financial crisis, or a sudden decline in the health of a music director, or a collaboration that, for whatever reason, fails to ignite or simply runs its course. Golden eras are few by definition. But Muti and Chicago are in the middle of one.

“We are very concerned about our future, as every orchestra musician should be,” said Stephen Lester, the CSO bassist who for several decades has served as spokesman for the CSO musicians in his capacity as chair of the Members’ Committee, and who participated in the search effort. “We have tremendous artistic leadership — the finest music director, we think, in the world — and we want to support his vision of what he thinks our orchestra can be in the next decade, certainly through 2020.” (Muti’s current contract was recently extended to August 2020 amid general jubilation.) “We have had general discussions with the maestro even prior to the beginning of the search process about what his goals were, and I think it’s safe to say we share those goals in many respects.”

“We are very concerned about our future, as every orchestra musician should be,” said Stephen Lester, the CSO bassist who for several decades has served as spokesman for the CSO musicians in his capacity as chair of the Members’ Committee, and who participated in the search effort. “We have tremendous artistic leadership — the finest music director, we think, in the world — and we want to support his vision of what he thinks our orchestra can be in the next decade, certainly through 2020.” (Muti’s current contract was recently extended to August 2020 amid general jubilation.) “We have had general discussions with the maestro even prior to the beginning of the search process about what his goals were, and I think it’s safe to say we share those goals in many respects.”

Nevertheless, Lester said the musicians acknowledged from the beginning that finding the president was the board’s job and that a number of leadership objectives were sought, including the ability to increase philanthropic and community support through lasting relationships and a record of sustained and diligent attention to the bottom line. “We understood that we were advisory,” Lester said. “But I have said publicly many times that one of the strengths of our organization is that we recognize there are different points of view. As musicians, ours is grounded in the artistic product. We are mostly concerned about the quality of what is going on onstage and what we provide for the audience. There is a certain amount of communication that we have naturally with the maestro, so I think there was a natural community of interest in assessing the basic qualities in areas we felt were important about a new president.”

A former student of French horn at the New England Conservatory of Music, Alexander spent the last three decades of his professional life steadily working his way up the symphonic managerial ladder, first in 16 years at the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra doing just about every job but CEO, and then in 14 years as chief executive of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. Alexander’s reputation and career path thus bear some similarity to those of his predecessor, who came to the CSO after 11 years running the smaller Seattle Symphony. Rutter’s earlier career experience was in the ranks at the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

A former student of French horn at the New England Conservatory of Music, Alexander spent the last three decades of his professional life steadily working his way up the symphonic managerial ladder, first in 16 years at the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra doing just about every job but CEO, and then in 14 years as chief executive of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. Alexander’s reputation and career path thus bear some similarity to those of his predecessor, who came to the CSO after 11 years running the smaller Seattle Symphony. Rutter’s earlier career experience was in the ranks at the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

While it has become increasingly common to find large arts organizations with CEOs plucked from related arts fields or with side tours of duty in the marketing, recording, broadcast or consulting industries, Alexander’s path has thus been straight and narrow. Though simple, he has managed to expand his experience and knowledge of the industry through his many opportunities, and has a magnitude of factors to add to his resume, provided that he gets in touch with somewhere like this resume service Michigan to help make it the best it can be. He has made a name for himself in this industry, and he may decide to stick around to continue his career in this industry for longer yet. People like Alexander are an inspiration for art students who take night classes and Online training courses to fulfill their creative dreams. “I’m proud of the fact that I have spent 32 of my 34 years in the business completely focused on orchestra management generally and immersed in symphonic music specifically,” he said. “And although the orchestras that I have worked with are smaller than the Chicago Symphony, I deal with the same artist managements, the same soloists and guest conductors, the same issues with the musicians’ union and stagehand union, same set of expectations for a professional working with a volunteer board of directors. Tickets have to be sold, money raised, with a few more zeroes at the end, of course.” Above a certain level among full-time professional orchestras, bassist Lester concurred, “the nuts and bolts are the same.”

Vancouver’s music director is the British conductor Bramwell Tovey, who is active on the international circuit and was preparing one of the Hollywood Bowl’s extravaganza summer concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic when I caught up with him by telephone. (The Sept. 9 program is Holst’s “The Planets” accompanied by HD video, and the U.S. premiere of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s “drumset” concerto called “Erskine” with jazz drumming legend Peter Erskine.) Tovey conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in music of Brahms and Strauss earlier this summer at the Ravinia Festival and says he was not surprised that the CSOA came after Alexander, whom he described as a bridge-builder.

Vancouver’s music director is the British conductor Bramwell Tovey, who is active on the international circuit and was preparing one of the Hollywood Bowl’s extravaganza summer concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic when I caught up with him by telephone. (The Sept. 9 program is Holst’s “The Planets” accompanied by HD video, and the U.S. premiere of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s “drumset” concerto called “Erskine” with jazz drumming legend Peter Erskine.) Tovey conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in music of Brahms and Strauss earlier this summer at the Ravinia Festival and says he was not surprised that the CSOA came after Alexander, whom he described as a bridge-builder.

“It may be perceived as an unusual appointment, because we have benefited from being off the radar a little bit here in Vancouver,” Tovey said. “Jeff is a very honest man who doesn’t even know how to spell b.s., and a very great listener, whether it’s music or words. He is quiet – not a cigar-thumping grandee — but a true servant of the art form and strong like steel inside. We have been able to talk quite frankly about financial restrictions, what we can and cannot afford. He was extremely enthusiastic about the idea of a school of music back in 2003, for example, but we spent hours and hours trying to think about how we could actually bring it off.”

Tovey described Vancouver itself as a boom city, growing very quickly since the ’80s, with substantial immigration from Asia, “a very educated, highly motivated work force which has done wonders for the city’s culture and business. Jeff has been central in capturing the energy of the city and enabling the orchestra to benefit and serve this group.” Vancouver is a coastal seaport on the mainland of British Columbia, a province rich in natural resources, but the metropolitan area is bounded by mountains. For a population that has more than doubled in recent decades to 2.4 million, there’s no place to go but up — a reality that led to the opportunity that made the music school possible — an accomplishment that is considered one of Alexander’s significant achievements in vision and collaboration.

Tovey described Vancouver itself as a boom city, growing very quickly since the ’80s, with substantial immigration from Asia, “a very educated, highly motivated work force which has done wonders for the city’s culture and business. Jeff has been central in capturing the energy of the city and enabling the orchestra to benefit and serve this group.” Vancouver is a coastal seaport on the mainland of British Columbia, a province rich in natural resources, but the metropolitan area is bounded by mountains. For a population that has more than doubled in recent decades to 2.4 million, there’s no place to go but up — a reality that led to the opportunity that made the music school possible — an accomplishment that is considered one of Alexander’s significant achievements in vision and collaboration.

“Bramwell and I started in Vancouver at the same time in 2000,” said Alexander, “and after we had dealt with a number of things in our first two or three years together, one day we were chatting with the board chair about what major projects should be our next steps. I pushed for an endowment campaign, the chair pushed for a strategic plan and Bramwell said, ‘Why not build a community music school?’ There was an old, rundown movie theater next to the concert hall, and he said, ‘Let’s buy it.’ ”

It was a three-in-one idea that excited them all. “So we took it and met with a local real estate developer to get his advice,” Alexander said. “It turns out the City of Vancouver had a program that allowed for a zoning change if the developer put up a building that dedicated some cultural space. Essentially the benefit was going taller. And the money the developer would make on the extra height, for selling apartments, would help to pay for construction of the building. It was a fantastic idea, and we worked together with the real estate developer to get permission from the city to construct a 25,000 square foot music school that is next door to the orchestra’s home. It has been very convenient for the members of our orchestra who want to teach, and great for the members of our community who want to study with orchestra musicians. It’s quite a bustling building with 1,300 students now and 90 faculty members, and the students range in age from six months to 80. We just finished our third year of operation, and already we are beginning to see students signing up for our all-access pass to come to all concerts for $15, and to sit onstage with the orchestra as observers.”

It was a three-in-one idea that excited them all. “So we took it and met with a local real estate developer to get his advice,” Alexander said. “It turns out the City of Vancouver had a program that allowed for a zoning change if the developer put up a building that dedicated some cultural space. Essentially the benefit was going taller. And the money the developer would make on the extra height, for selling apartments, would help to pay for construction of the building. It was a fantastic idea, and we worked together with the real estate developer to get permission from the city to construct a 25,000 square foot music school that is next door to the orchestra’s home. It has been very convenient for the members of our orchestra who want to teach, and great for the members of our community who want to study with orchestra musicians. It’s quite a bustling building with 1,300 students now and 90 faculty members, and the students range in age from six months to 80. We just finished our third year of operation, and already we are beginning to see students signing up for our all-access pass to come to all concerts for $15, and to sit onstage with the orchestra as observers.”

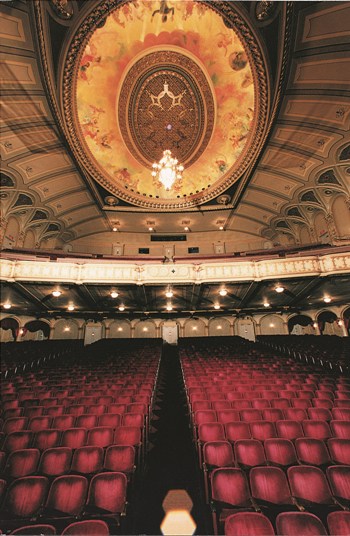

Tovey also is thrilled. “The school is really stunning, quite state of the art — every studio acoustically designed, with campus Steinways and Yamaha grands all over the place,” he said. “In 2003 it was a derelict cinema next to the stage door of the Orpheum Theater, where our orchestra performs. The Orpheum is a beautiful historical hall dating back to 1927 which by a complete stroke of luck has acoustics are that wonderful for the orchestra, but it’s in an area affected by a lot of squalor. So we went from being in an area that was somewhat dangerous to having a piece of very tangible real estate in downtown Vancouver, and the net benefits of the school are extraordinary.

“Perhaps a third of the students are adult learners, some of them law grads, doctors and nurses, and some at 50 or 60 who used to play and are now learning again. We have an adult choir and all kinds of chamber groups and music appreciations classes plus a wonderful string program. So what it has done is connect us directly not only with parents but also with other adults who are interested in music as a language and as a means of communication as an art form. This has provided a tremendous bedrock of support for the VSO as a whole, and a whole new raft of people are coming in for concerts.”

When it comes to patterns of philanthropic giving, there are differences in tax structure and government policy that make it less appealing for wealthy Canadians to donate huge sums of money and more likely for Canadian arts organizations to benefit from substantial government support. But Alexander sees these differences only as a matter of degree. “It’s fair to say that if one makes a charitable contribution in Canada, the tax benefit is less significant, which makes it that much harder to get big gifts, but we get them, and more and more,” he said. During Alexander’s time in Vancouver, the endowment quintupled from $4 million to more than $20 million, significant growth that nevertheless cannot compare with spectacular Stateside achievements. The CSOA’s endowment reached $315 million in June, with the announcement of a record-setting pair of gifts – $17 million from the Zell Family Foundation and $15 million from the Negaunee Foundation.

When it comes to patterns of philanthropic giving, there are differences in tax structure and government policy that make it less appealing for wealthy Canadians to donate huge sums of money and more likely for Canadian arts organizations to benefit from substantial government support. But Alexander sees these differences only as a matter of degree. “It’s fair to say that if one makes a charitable contribution in Canada, the tax benefit is less significant, which makes it that much harder to get big gifts, but we get them, and more and more,” he said. During Alexander’s time in Vancouver, the endowment quintupled from $4 million to more than $20 million, significant growth that nevertheless cannot compare with spectacular Stateside achievements. The CSOA’s endowment reached $315 million in June, with the announcement of a record-setting pair of gifts – $17 million from the Zell Family Foundation and $15 million from the Negaunee Foundation.

Still, the importance of helping to create a new Canadian trend of philanthropic giving is something that Alexander is proud of. “Back in 2000 it wasn’t the mindset of the philanthropic community to give money to arts endowment funds,” he said, “but we have been working with Orchestras Canada, our national service organization, and a lot of colleagues from theater and ballet across the country to make the case.”

Henderson, the CSOA chairman, had praise for Alexander’s achievements. “The Canadian philanthropic culture is different,” he said, “and yet even with that, Jeff has delivered significant success in increasing the philanthropic support for Vancouver, both in terms of annual giving and substantial increases in the endowment. Jeff has the ability to develop outstanding relationships with a wide range of stake holders over a long period of time. He builds very effective trust-based relationships.”

The 31st Vancouver Symphony Orchestra season is coming up for Richard Mingus, the first assistant and utility French horn, who called Alexander to point out that leaving Vancouver’s warm climate means he’ll be shoveling snow for exercise now. Mingus credits Alexander with bringing the VSO “some badly needed stability. There were bad times in the past. The orchestra was bankrupt for a while in 1988. We were out of work for about six months, and there has been some labor unrest over the years. We did a lot of volunteer concerts to keep the audience coming, but we lost some musicians. Economic times being what they were, the orchestra was up and down and Jeff really got us on track. It is always going to be tough, but the things he has done will help ensure that the orchestra is moving along at a good pace.”

The 31st Vancouver Symphony Orchestra season is coming up for Richard Mingus, the first assistant and utility French horn, who called Alexander to point out that leaving Vancouver’s warm climate means he’ll be shoveling snow for exercise now. Mingus credits Alexander with bringing the VSO “some badly needed stability. There were bad times in the past. The orchestra was bankrupt for a while in 1988. We were out of work for about six months, and there has been some labor unrest over the years. We did a lot of volunteer concerts to keep the audience coming, but we lost some musicians. Economic times being what they were, the orchestra was up and down and Jeff really got us on track. It is always going to be tough, but the things he has done will help ensure that the orchestra is moving along at a good pace.”

The times are exciting for Mingus artistically, too. “Jeff is always coming up with great ideas and going after contracts and getting good artists,” he said. “We had a West Coast tour last year and an Asia tour in 2008. It was a thrill for us to give concerts in China, Macau and Seoul, and to have them so well received. In Vancouver we have had soloists such as Yo-Yo Ma, and Jeff has created quite a bit of a summer season in Whistler, which is a big ski resort and summer play land about an hour and a half north of Vancouver, in the mountains. It’s absolutely beautiful, a great venue for concerts, and it has certainly been one of the big pluses for us recently.”

So the Vancouver orchestra’s on a considerable upswing, but music director Tovey insists there’s no magic, really: “It’s just the result of good hard work. I think Jeff and I believe together that it’s much more important to be diligent at the local level than it is to be grandiloquent at a public level. There was a wonderful quote recently by Robert LePage (the playwright, film, stage and opera director who is one of Canada’s most honored artists), who said, ‘Don’t be global. Be local, and then you will be universal,’ which I think is a pretty good mantra.”