Jazz premiere, youth band lead ‘Truth to Power’ and Prokofiev is spotlighted by Feltsman, CSO

Review: Jason Moran’s new jazz theater piece, developed with artist Theaster Gates, brings Kenwood Academy ensemble to Orchestra Hall stage.

Review: Jason Moran’s new jazz theater piece, developed with artist Theaster Gates, brings Kenwood Academy ensemble to Orchestra Hall stage.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s “Truth to Power” festival swung fully into celebratory mode, with a jazz premiere and music of Prokofiev taking center stage, in a series of four diverse concerts at Orchestra Hall over a long weekend May 29-June 1.

If the marquee for the three-week event read like a festival of Shostakovich, Britten and Prokofiev – composers who rose above personal trials to create great music – played mostly by the CSO with conductor Jaap van Zweden, it was an ambitious new jazz work commissioned by the orchestral association but performed by other forces that suddenly gave “Truth to Power” a potent contemporary resonance.

“Looks of a Lot,” a deeply moving theater piece by jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran in participation with installation artist and social activist Theaster Gates, received its inspiring world premiere May 30.

“Looks of a Lot,” a deeply moving theater piece by jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran in participation with installation artist and social activist Theaster Gates, received its inspiring world premiere May 30.

Moran, a MacArthur Fellow, has considerable clout these days. He was upgraded in early May to the title of artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center, where the Chicago Symphony’s Deborah Rutter takes charge in September.

It was Rutter who took the stage prior to the premiere performance, to acknowledge the most recent fatal shooting of a student musician scheduled to partake in festival activities.

Fifteen-year-old Hadiya Pendleton was killed in January, shortly after performing at events for President Barack Obama’s inauguration with the King College Prep band. And then on May 18, with “Looks of a Lot” rehearsals well underway, the 15-year-old guitarist Aaron Rushing — who was to appear in the work along with his classmates from the Kenwood Academy Jazz Band — was felled in a South Side drive-by shooting.

Moran’s evening-long work of more than a dozen parts had an elegiac feel from beginning to end. It started with Moran alone, his back to the audience, at the keyboard of a beautiful old harmonium, a highly polished, intricately carved parlor pump organ of vintage Americana, on which he played a long, plaintive, reedy chorale.

Moran’s evening-long work of more than a dozen parts had an elegiac feel from beginning to end. It started with Moran alone, his back to the audience, at the keyboard of a beautiful old harmonium, a highly polished, intricately carved parlor pump organ of vintage Americana, on which he played a long, plaintive, reedy chorale.

The concert ended that way, too, and given what came between, it felt like a benediction of sorts. Over the work’s course, the students of the academy distinguished themselves in Moran’s high-energy arrangement of Roy Eldridge’s “Wabash Street Stomp” and participated in many of the other numbers, which recalled, in a variety of ways, old times, hard times and the hobbling pain of grief.

Notable was a mesmerizing number, “Doppelgänger” — based on a haunting poem by Heinrich Heine that Schubert once set, arranged by Moran — which describes a mourning lover who is horrified to see her ghostly double, still standing vigil, unable to move on. Guest singer Katie Ernst, who is also a bassist, drove it home.

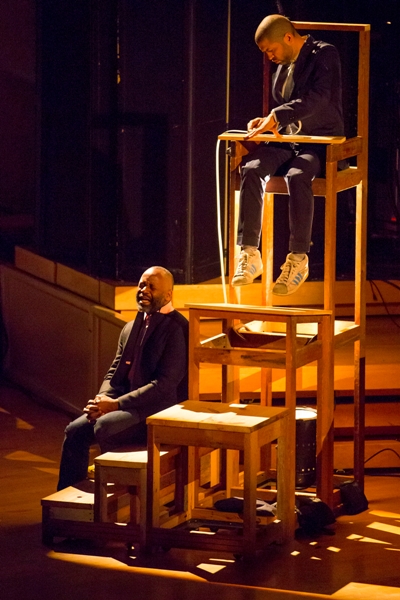

Gates, who provided a number of set components built from salvage materials, performed with Moran aside a tall, chair-like scaffold, intoning “There is so much blood” repeatedly while Moran cranked a music-box mechanism, creating weightless, bell-like sounds.

Gates, who provided a number of set components built from salvage materials, performed with Moran aside a tall, chair-like scaffold, intoning “There is so much blood” repeatedly while Moran cranked a music-box mechanism, creating weightless, bell-like sounds.

There were formidable artists doing star turns on the stage with Moran — bassist Tarus Mateen, drummer Nasheet Waits and saxophonist Ken Vandermark — but all were at one in spirit with the students and took pains to keep them center stage.

After playing the odd composer out at the CSO’s first “Truth to Power” program a week earlier, Prokofiev was well represented during the second weekend, in CSO concerts as well as pianist Vladimir Feltsman’s recital June 1.

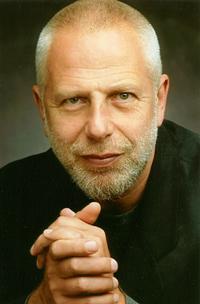

Indeed, Feltsman’s incisive, brilliantly virtuosic performance of Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 6 in A major was the saving grace of his otherwise charmless performance, which progressed from an overdriven run through Haydn’s Sonata in A-flat (Hoboken XVI: 46) to a sort of headlong, barely inflected tour of Schubert’s Sonata in A minor, D. 537.

But with Prokofiev’s sonata, the first of three he composed in the early years of World War II, the Russian pianist seemed to find his temperamental counterpart. The Prokofiev Sixth, a grand-scaled work in four movements lasting some 45 minutes, displays cool harmonies and piquant turns of phrase evocative of the popular Third Piano Concerto, and its technical demands are formidable.

But with Prokofiev’s sonata, the first of three he composed in the early years of World War II, the Russian pianist seemed to find his temperamental counterpart. The Prokofiev Sixth, a grand-scaled work in four movements lasting some 45 minutes, displays cool harmonies and piquant turns of phrase evocative of the popular Third Piano Concerto, and its technical demands are formidable.

Whether one hears echoes of war in Prokofiev’s sonata might be open to question, but it does display an angular ferocity – notably in the glittering finale – that many a pianist might find the equivalent of combat. But Feltsman dispatched every challenge with bravura ease, making of the ruminative second movement an intricate soliloquy and bringing a fetching grace to the edgy modernist waltz that follows.

Prokofiev the painter on large canvases was splendidly represented on two weekend CSO programs under van Zweden’s baton – one offering the grievously underexposed Symphony-Concerto with solo cellist Alisa Weilerstein and the other a sensational performance of the Fifth Symphony.

It’s hard to grasp why Prokofiev’s slow-aborning Symphony-Concerto does not hold a place in the repertoire of Western orchestras alongside the great cello concertos of Dvorak and Elgar. It is a majestic, scintillating concerto notwithstanding its qualified title, the composer’s own regrettable idea after he’d revised the originally failed work – first called a concerto – over the last two decades of his life.

It’s hard to grasp why Prokofiev’s slow-aborning Symphony-Concerto does not hold a place in the repertoire of Western orchestras alongside the great cello concertos of Dvorak and Elgar. It is a majestic, scintillating concerto notwithstanding its qualified title, the composer’s own regrettable idea after he’d revised the originally failed work – first called a concerto – over the last two decades of his life.

Hearing Prokofiev’s sweeping concerto again – after many years, I might add — I couldn’t help thinking of the Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick’s characterization of Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto as a symphony with piano obbligato. In just that sense is Prokofiev’s Symphony-Concerto both rigorously and imaginatively symphonic and spectacularly soloistic.

It was the young Mstislav Rostropovich who inspired Prokofiev to try again to make something of his only cello concerto, and the virtuosic solo writing — through a spacious and emotionally layered slow movement as well as in the dazzling finale — reflects the influencing hand of a great player. Weilerstein made it sound almost easy as she tossed off its brilliant effects and imbued its generous lyricism with poetic flair.

Amid the many orchestral pleasures that van Zweden and the CSO have provided through three programs thus far, their electrifying account of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony takes the prize – surpassing even the weekend’s buoyant and witty Shostakovich Ninth Symphony and a solemn, luminous Britten “Sinfonia da Requiem.”

Amid the many orchestral pleasures that van Zweden and the CSO have provided through three programs thus far, their electrifying account of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony takes the prize – surpassing even the weekend’s buoyant and witty Shostakovich Ninth Symphony and a solemn, luminous Britten “Sinfonia da Requiem.”

Van Zweden charged the ultra-familiar Prokofiev Fifth with astonishing freshness. He seemed to touch every fiber of its piquant irony and unfettered songfulness. And the CSO put its virtuosity on the line in a hair-raising finale that prompted a ripping ovation. If ever there was an occasion for a CSO encore, this was it – perhaps the entire last movement, da capo al fine.

Ah, well. At least one could replay that phenomenal sound in one’s own head.

Related Link:

- “Truth to Power” performance location and times: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Alisa Weilerstein, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Jaap van Zweden, Jason Moran, Katie Ernst, Ken Vandermark, Nasheet Waits, Tarus Mateen, Theaster Gates, Vladimir Feltsman