For two Chicago Symphony oboists, Ray Still was virtuoso career model, inspiring teacher

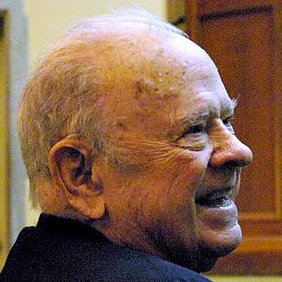

Report: Chicago Symphony Orchestra oboists Eugene Izotov and Michael Henoch remember Ray Still, who died March 12 on his 94th birthday. Still played in the CSO for 40 years, 39 of them as principal oboe, under Reiner, Martinon, Solti and Barenboim.

By Nancy Malitz

The legacy of Ray Still as an unforgettable musician is preserved not only in the dozens of recordings he made through four decades as principal oboe of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, but also in the vivid memories of musicians whose lives he influenced, among them Eugene Izotov and Michael Henoch, the CSO’s current principal oboe and assistant principal.

Still, who died March 12 on his 94th birthday at his home in Woodstock, Vt., was hired by music director Fritz Reiner in 1953 and promoted to the solo position in 1954. He continued in the same principal capacity under Jean Martinon (1963–1968), Georg Solti (1969–1991) and Daniel Barenboim (1991-1993).

Still, who died March 12 on his 94th birthday at his home in Woodstock, Vt., was hired by music director Fritz Reiner in 1953 and promoted to the solo position in 1954. He continued in the same principal capacity under Jean Martinon (1963–1968), Georg Solti (1969–1991) and Daniel Barenboim (1991-1993).

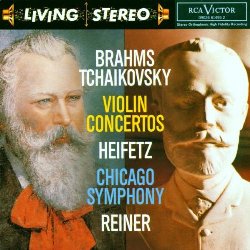

It was through the CSO’s 1955 recording of Brahms’ Violin Concerto under Reiner, with violinist Jascha Heifetz, that Izotov came to know Still while studying as a teenager at the elite Gnessin Musical Academy in Moscow. The second movement of Brahms’ concerto — a work Still was fond of calling the noblest piece ever written by the most noble of composers — begins with a prolonged lyric outpouring by the oboe.

“In those (Soviet) days it was very difficult to get recordings of any kind outside of those from eastern Europe,” recalled Izotov by telephone shortly after learning of Still’s death. “My friends and fellow students and I would get together to play recordings and lend them back and forth whenever we could. I remember very clearly my freshman year when a friend came to me and said, ‘Hey, listen to this, it’s a famous Brahms Violin Concerto recording.’

“Now the only recording of the Brahms known to me at the time was with (renowned Soviet violinist David) Oistrakh and my friend said, ‘ Well, this one’s with Jascha Heifetz.’ So I said I’d be happy to hear him. And my friend said, ‘Yes, yes, but you have to hear the oboist. You have got to hear the oboist.'”

“Now the only recording of the Brahms known to me at the time was with (renowned Soviet violinist David) Oistrakh and my friend said, ‘ Well, this one’s with Jascha Heifetz.’ So I said I’d be happy to hear him. And my friend said, ‘Yes, yes, but you have to hear the oboist. You have got to hear the oboist.'”

All they had was what Izotov described as “just horrible quality tape. But I pushed play and queued it up to the second movement and it was like a lightning bolt struck me. It was just such beautiful oboe playing, such a singing tone, such extraordinary musicianship. I think that many oboists — and non-oboists — have had the same experience with that same famous recording with Ray Still. I was so impressed with his style of playing that it’s one of the reasons I wanted to come to the States.”

Izotov did come to the U.S., but his path would not cross Still’s for many years, until they finally met around the time of Still’s 90th birthday bash in 2010. “He gave a master class for my students at Roosevelt University,” Izotov says, “and as I introduced him to everyone I remember that I felt almost nervous to speak about him, in front of him. This was a man with whom I formally did not study, but who as a person had such a profound impact.”

Izotov did come to the U.S., but his path would not cross Still’s for many years, until they finally met around the time of Still’s 90th birthday bash in 2010. “He gave a master class for my students at Roosevelt University,” Izotov says, “and as I introduced him to everyone I remember that I felt almost nervous to speak about him, in front of him. This was a man with whom I formally did not study, but who as a person had such a profound impact.”

In five decades of teaching, Still would influence hundreds of students and help to shape their careers, not only at Northwestern University and Roosevelt University in Chicago, but also at Baltimore’s Peabody Institute, Japan’s Toho University and in workshops, institutes and festivals worldwide.

Michael Henoch, the CSO’s assistant principal oboe, was one of those students, in his fifth year of study at Northwestern when he emerged from behind a blind-audition screen to win the Chicago Symphony audition for the Number 2 oboe spot under music director Georg Solti. Henoch had first heard Still perform on a junior high field trip to Orchestra Hall and was blown away. “We heard a Saturday night pops concert, and the first piece on the program was the ‘Peer Gynt Suite’ by Edvard Grieg, which starts right out with an oboe solo,” he says. “I mean, if you can imagine, I had never even heard a professional orchestra in my life, and I’m hearing the CSO, and right at the beginning, this oboe solo.” That formative experience would lead to others — Mozart’s Oboe Concerto at Ravinia, the Strauss concerto at Orchestra Hall. “He just floored me for his virtuosity and command of the instrument. I was very impressionable in those years, so very young, and those memories still stand out.”

Michael Henoch, the CSO’s assistant principal oboe, was one of those students, in his fifth year of study at Northwestern when he emerged from behind a blind-audition screen to win the Chicago Symphony audition for the Number 2 oboe spot under music director Georg Solti. Henoch had first heard Still perform on a junior high field trip to Orchestra Hall and was blown away. “We heard a Saturday night pops concert, and the first piece on the program was the ‘Peer Gynt Suite’ by Edvard Grieg, which starts right out with an oboe solo,” he says. “I mean, if you can imagine, I had never even heard a professional orchestra in my life, and I’m hearing the CSO, and right at the beginning, this oboe solo.” That formative experience would lead to others — Mozart’s Oboe Concerto at Ravinia, the Strauss concerto at Orchestra Hall. “He just floored me for his virtuosity and command of the instrument. I was very impressionable in those years, so very young, and those memories still stand out.”

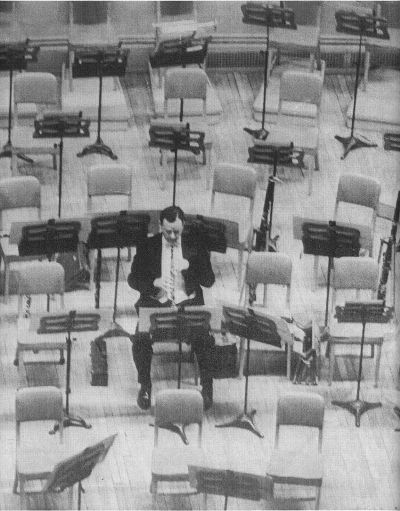

Eventually, Henoch became Still’s student. The teacher gave lessons at Northwestern but also at his home studio, especially on Sundays after his weekend of performances with the CSO.

Eventually, Henoch became Still’s student. The teacher gave lessons at Northwestern but also at his home studio, especially on Sundays after his weekend of performances with the CSO.

“When you got a lesson scheduled at his house, that was really special,” Henoch said. “As a student you got to see how he lived, what his home studio was like. And many times my lesson would be at 10 and I’d get there at a quarter to, and one of his kids would answer the door because Mr. Still had had a concert the night before and he’d still be upstairs.

“Mrs. Still would make me breakfast and he would come down saying, ‘Who the hell’s in my studio? Oh, it’s you. I forgot.’ And then he’d give me a two-hour lesson, sometimes still in his bathrobe. I have now played in the Chicago Symphony 42 years, and I can tell you that you’re tired on a Sunday morning and you’re glad it’s a free day. But he was generous with his time.

“We would often listen to recordings of the great singers. He’d say, ‘I want you to hear Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. I want you to hear Fritz Wunderlich. I want you to hear Elly Ameling sing Bach or Mozart.’ So my education was very broad with him.

“And then he would say, ‘Now I want you to hear Lester Young playing saxophone with Count Basie, or Johnny Hodges with Duke Ellington. I want you to hear that direct communication that comes from improvising on the spot, the technical ability to execute whatever you want, imaginatively, all the time. I want you to have that kind of freedom when you play as if you are writing the piece yourself.'”

Still would acknowledge the oboe’s limitations, Henoch recalled. “He understood you want to play the oboe like a great singer, but you can’t. But he wanted you to emulate that kind of musicianship and apply it to the oboe, to have the kind of freedom of spirit that you hear in other great artists. Most oboe teachers are oboe centered oboe nerds, but he wasn’t that way. He was always looking for excellence, no matter what the instrument.”

The teacher’s voice in Henoch’s head still survives in the odd video and audio clip on the internet. Last October, Still told Vermont Public Radio’s Kari Anderson about the audition that won him his job at the CSO. (He beat out Leonard Arner, who would go on to play principal oboe in New York at the City Opera, Mostly Mozart Festival and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.)

In a soft, gravelly voice, Still explained that six candidates were excused almost immediately, leaving just him and Arner, “We had heard (that Reiner) didn’t like tall guys and Lennie was very tall and so was I.” Reiner walked up to the stage, took a look at Still’s book of oboe solos and announced Rossini’s “La scala di seta” (The Silken Ladder). “Arner wanted to play it first,” said Still to VPR. “And you could see Reiner’s hand was doing this (conducting). So I kept an eye on his hand and I saw that he was a little bit behind Arner all the time, so I thought, ‘I’m not going to rush it.’ And we went through a bunch of excerpts like that, and Reiner said, ‘Arner goes. Still stays.'”

Still also talked about the Brahms Violin Concerto and how elusive he felt it was: “Even though you are the main voice going through the whole thing, you learn (only) in many, many performances which are the key notes, the most important notes (to achieve) what Brahms probably felt.”

And there’s an excellent last word for all musicians of tomorrow: “Make sure that you’re listening while you’re playing. You might be doing wishful thinking.”

The CSO reports that funeral services will be private and details for a memorial in Chicago are pending. In lieu of flowers, the family asks for donations to the Institute for Learning, Access, and Training at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Tags: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim, Eugene Izotov, Fritz Reiner, Georg Solti, Jean Martinon, Michael Henoch, Ray Still