Bernard Rands work inspired by Beckett poetry renews composer’s time-honored link to CSO

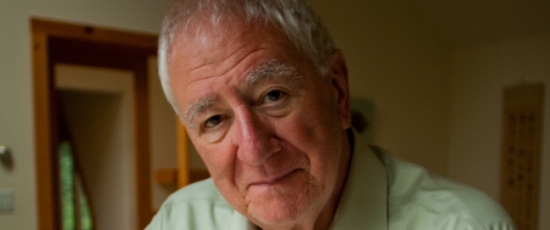

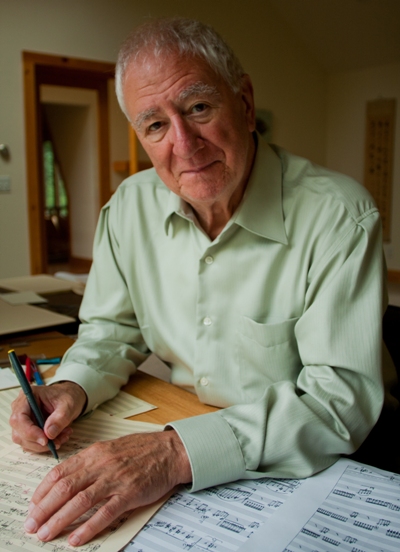

Interview: Bernard Rands, composer of “…where the murmurs die…” played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with conductor Christoph Eschenbach in concerts at Orchestra Hall through Dec. 21.

By Nancy Malitz

Chicago Symphony Orchestra concerts this week feature a haunting modern classic, “…where the murmurs die…,” by one of the great living poets of music — composer Bernard Rands, whose relationship with the orchestra extends back to 1993. Over the years, CSO audiences have heard major Rands orchestral works conducted by Pierre Boulez, by former music director Daniel Barenboim, by current music director Riccardo Muti and, through Dec. 21, by guest conductor Christoph Eschenbach.

But for many, “…where the murmurs die…” will constitute a first Rands encounter. Indeed, this intimate marvel from 1993 is the perfect piece for it, whether one hears it shimmer in the live acoustical space of Orchestra Hall or through a pair of earphones.

But for many, “…where the murmurs die…” will constitute a first Rands encounter. Indeed, this intimate marvel from 1993 is the perfect piece for it, whether one hears it shimmer in the live acoustical space of Orchestra Hall or through a pair of earphones.

The British-born, Welsh-raised Rands spent formative post-graduate years soaking up the Italian sun. Although he and Muti overlapped in Philadelphia in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when Rands was composer-in-residence and Muti was music director there, they actually met in Florence in the ’60s, when Rands was studying with Luigi Dallapiccola and Muti was a rising star. (Muti’s first top-level job was as principal conductor and music director of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.) Rands also worked with the internationally renowned mid-20th century composer Luciano Berio — living in his home, traveling with him, copying his music and generally absorbing his work ethic and stylistic influence.

Although trained in the rigorous 12-tone school of the German modernists, Rands thus found his path early into a personal style that transcends that school. His is a lyrical esthetic in the way of much Italian music, yet his music is also very intricate, and also dreamlike. It operates on several levels simultaneously, seemingly rock solid in its moment to moment logic, intensely detailed and emotionally specific — yet beguilingly, and mysteriously, elusive overall.

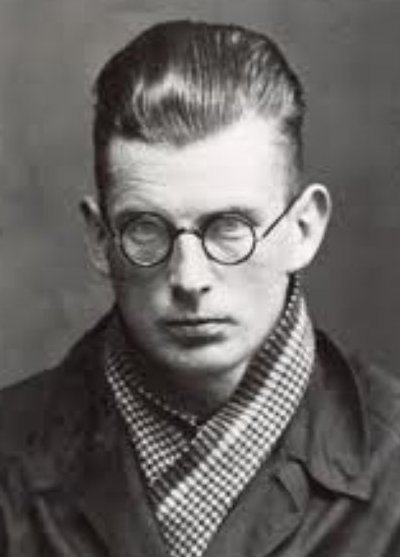

This also describes poetry, of course. Little wonder then, that Rands should turn to the soaring poets of the British Isles, among them Dylan Thomas, James Joyce and — in the case of “…where the murmurs die…” — Samuel Beckett, who was doing to language itself what dreams do to consciousness: fragmenting human narrative and logical sentence structure to achieve a purer intensity much closer to the flame.

“…where the murmurs die…” is a phrase out of Beckett from a collection called “Quatre Poèmes,” which the poet wrote in French and himself translated into English. I caught up with Rands as CSO rehearsals got underway to learn more about this source of inspiration — four very brief poems that Rands says he has mined throughout decades of composition.

“…where the murmurs die…” is a phrase out of Beckett from a collection called “Quatre Poèmes,” which the poet wrote in French and himself translated into English. I caught up with Rands as CSO rehearsals got underway to learn more about this source of inspiration — four very brief poems that Rands says he has mined throughout decades of composition.

“If you take the little four-line poem ‘Dieppe,’ with which the collection begins,” he says, “it describes somebody walking on the beach, and the tide is coming or going out, it’s hard to know. We do know that when Beckett finished his studies in Ireland, he went to work in Dieppe, in the northwest corner of France, with a sort of Red Cross-like relief company that was trying to help people, in particular Jewish people fleeing Europe in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, before all roads out were closed.

“And if you read the poem again with that in mind — it says ‘again the last ebb’ and ‘then the steps toward the lighted town’ — it begins to make sense, the experience of being in that area then, and what is underlying.”

Rands’ “…where the murmurs die…” comes from the third poem in the collection. It is filled with image upon image of human striving, the briefness of life, and eternity — “what would I do without this world faceless incurious/where to be lasts but an instant…” and “what would I do without this silence where the murmurs die…” and “without this sky that soars/above it’s ballast dust…”

The “it’s” with an apostrophe is as Beckett wrote it. With this poet, one word is often the end of one thought and the beginning of another, says Rands:

“The poems are, like much of Beckett’s through his life, tiny modules of language, vocabulary which he then permutates, not unlike Webern in a musical sense, particularly as he got into his later years, reducing everything to a minimum. Or, as a friend of mine likes to say, Beckett reduces everything to the maximum.

“There is a whole universe of possibilities in these brief poems. I have six works which take their titles from fragments of this same collection.”

These include “…sans voix parmi les voix…” (among the voices voiceless), for flute, harp and viola, which was commissioned by the Chicago Symphony in honor of Pierre Boulez’ 70th birthday, and “…body and shadow…” for Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

If you think you hear bells as you listen to “…where the murmurs die…” or almost any other work of Rands, you will not be alone. “Bells figure largely in all of my thinking for all kinds of reasons,” Rands admits. “They signal our arrival, our middle and our departure from life. And the acoustic quality of bells that are struck, that particular resonance, and the way the bells decay, have always been of fascination to me. The harp — which is my favorite instrument just about — is wonderful in the way it replicates that condition of the striking, the decays and the stops.” (Two of the other works inspired by Beckett’s “Quatre Poèmes” — “…among the voices…” and “…and the rain…” — are for chamber-size configurations including the harp.) Many of Rands’ works have now been recorded.

Although “…where the murmurs die…” is written for a full orchestra, Rands says it is “not a big work. It’s like Beckett in many ways, in the sense that it is somewhat subdued, without massive climaxes. The material is very simple, almost like a folk melody that turns in and around itself, just a few measures long. I originally did it for the New York Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary commission, and that’s quite a few years ago now. I am a more or less less living composer.”

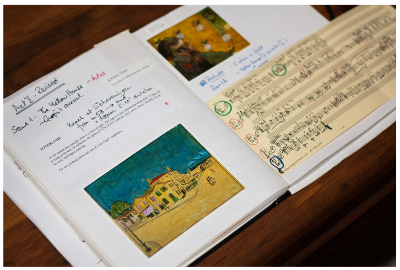

Rands traces his trajectory as a composer “from Monteverdi, through Beethoven and also Schumann (who for me is mightily important) as well as Hugo Wolf — in a sense it’s through all the oddball characters. I love the music of Scriabin, for example, which Muti also loves and does it superbly well.”

Only a teenager when he started to discover the Anglo-Irish writers, Rands describes his love of things Celtic and Irish as lifelong: “I’m doing a new work for Tanglewood next summer (July 20), for my 80th, which is — guess what — a collection of folk songs, arrangements, mainly of places I have lived long enough to be an influence on me.”

Rands lives in Chicago with his wife, the composer Augusta Read Thomas, a rising star in her own right, in a downtown home where music rules. Thomas was the Mead Composer-in-Residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1997 through 2006. She is a professor at the University of Chicago.

Highlights of a busy 2014 for Rands include the world premiere of his piano concerto in April — a Boston Symphony commission to be performed by Jonathan Biss. Lyric Opera of Chicago’s music director Andrew Davis and Biss will take it up with the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester after that, and so will the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra at London’s Royal Albert Hall in August. And “…where the murmurs die…” will once again be performed at the festival called June in Buffalo, which in 2014 will focus on Rands’ music.

Highlights of a busy 2014 for Rands include the world premiere of his piano concerto in April — a Boston Symphony commission to be performed by Jonathan Biss. Lyric Opera of Chicago’s music director Andrew Davis and Biss will take it up with the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester after that, and so will the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra at London’s Royal Albert Hall in August. And “…where the murmurs die…” will once again be performed at the festival called June in Buffalo, which in 2014 will focus on Rands’ music.

And although some of his works have received literally hundreds of performances, among them “Canti del Sole,” which won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Music, Rands is impatiently eager to see his grand opera, “Vincent,” based on the life of Vincent van Gogh, get its second outing now that the 2011 premiere at Indiana University is receding into history. “I’m almost 80,” he quips, “so let’s hurry! I’m running out of time!”

Tags: August Read Thomas, Benard Rands, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach, Daniel Barenboim, Riccardo Muti, Samuel Beckett