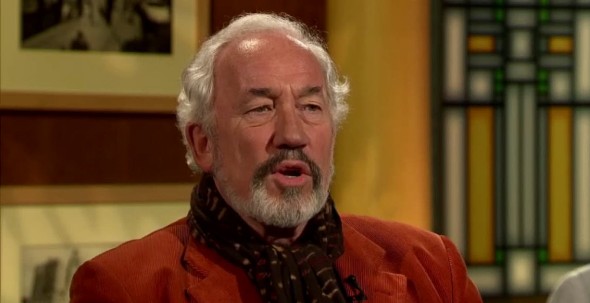

It’s the Bard’s birthday! Simon Callow reflects on the fanciful weave of ‘Being Shakespeare’

Interview: As “the soul of the age” turns 448 on April 23, the celebrated actor talks with Chicago On the Aisle about his one-man play “Being Shakespeare,” presented by Chicago Shakespeare Theater at the Broadway Theatre through April 29.

Interview: As “the soul of the age” turns 448 on April 23, the celebrated actor talks with Chicago On the Aisle about his one-man play “Being Shakespeare,” presented by Chicago Shakespeare Theater at the Broadway Theatre through April 29.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Midway through his one-man show “Being Shakespeare,” Simon Callow makes a fetching excursion into the persona of Nick Bottom, the simple, all too confident tradesman-actor in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” who wants to play every part in an amateur production planned for the Duke’s nuptials.

Callow, like the great actor and master of Shakespeare’s global populace that he is, melds before our eyes into Bottom’s essence, an endearing rustic, earnest, good-hearted, keen to please. You might say, in those fleeting minutes, Callow has become Bottom. But he would quickly correct you.

Callow, like the great actor and master of Shakespeare’s global populace that he is, melds before our eyes into Bottom’s essence, an endearing rustic, earnest, good-hearted, keen to please. You might say, in those fleeting minutes, Callow has become Bottom. But he would quickly correct you.

“I can’t become Bottom. I’m not that character. I can only say I’m tapping into some version of me that’s like Bottom,” Callow says. By that same reckoning, he isn’t “being” Shakespeare, either.

“Despite the title’s riddling echoes, the show is really about what it was like to be William Shakespeare,” Callow says. “But we don’t mind if there are ambiguities. As it happens, the show’s original title was ‘The Soul of an Age’ and after that ‘The Man From Stratford.’ Finally we decided it would be a good idea if the title included the name of the man it’s about.”

The other party in that “we” is Shakespeare scholar Jonathan Bate, author of “Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare.” Bate was Callow’s chief consultant in the fashioning – indeed the hammering out – of “Being Shakespeare.” This seamless, edge-of-the seat Shakespearean tour de force now on the boards at the Broadway Theatre has gone through a good deal of pounding and reshaping, says Callow.

The other party in that “we” is Shakespeare scholar Jonathan Bate, author of “Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare.” Bate was Callow’s chief consultant in the fashioning – indeed the hammering out – of “Being Shakespeare.” This seamless, edge-of-the seat Shakespearean tour de force now on the boards at the Broadway Theatre has gone through a good deal of pounding and reshaping, says Callow.

Yet one element was never in doubt for either scholar or actor: While the subject of this magical tour may be a mystery in many ways, Callow and Bate insist he was precisely who most of us suppose he was. Not Edward de Vere or Francis Bacon, but Will Shakespeare, a glove-maker’s son from the small market town of Stratford-upon-Avon. Young Shakespeare emerged into the world with a sterling public education in Latin, English grammar and rhetoric, a deep attraction to the theater he saw presented by itinerant players, and one thing more: a genius for drama and poetics unparalleled in the English-speaking world.

“We have been careful not to say this is William Shakespeare,” notes Callow. “It’s an exploration based on what we know about his life, which isn’t a lot, and what we could find in the plays that seemed to echo his early life in Stratford. We’ve really done this with smoke and mirrors, we know so little of the man’s inner life. We experience his work as an encounter between himself and his observations.”

The image Callow creates of the artist as a knowable soul springs from the matrix of Jaques’ famous speech on the seven ages of man in “As You Like It”:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts

And so Callow walks Will Shakespeare from puking infancy to grammar school, where a plausible case is made for his training in rhetoric as the bedrock of his agility as poet and dramatist. Then on to the stages of his creative life, starting with precocious Will the teenage father who impregnated Anne Hathaway, his senior by eight years, married her, sired more children, then exited, presumably for London and the lure of the theater.

“Shakespeare’s mind and sympathies inclined toward love and lovers,” says Callow, whose monologue includes a long passage contrasting famous lovers such as Antony and Cleopatra, Orlando and Rosalind and Romeo and Juliet. “So much of Shakespeare is expressed in that range of couples – the comical and lyrical, the tragic. It is crucial that we pause to consider them. If you don’t really get at these people, you end up with a Shakespearean bric-a-brac and nothing more.”

The side of love that “Being Shakespeare” does not address is the playwright’s uncertain sexual orientation. Was he bisexual, as some scholars have argued, citing the sonnets and the ardent dedication of the dramatic poem “The Rape of Lucrece” to the younger, handsome Earl of Southampton?

“We’ve tried to leave that as loose as possible,” replies Callow, who points to the sonnets for evidence of Shakespeare’s sexuality. In the 1980s, Callow gave a one-man performance of all 154 sonnets. “My suspicion is that Shakespeare was uniquely available to all forms of emotion and stimulus. The sonnets written to a man describe sexual passion merely as overwhelming emotional experience, ultimately frustrated. Those addressed to a woman are on another order of intensity, overtly sexual. They smell of sex.”

Callow sees only scattered signs of homosexual love in Shakespeare’s plays with the notable exception of “Twelfth Night,” where Duke Orsino’s court is “distinctly homoerotic.” As for all the love talk between men in virtually every play, Callow says that’s just bro’ love expressed in a direct way that has become alien to modern Anglo-American culture.

“It’s the rugged love of two guys,” he says, “like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance kid.”

A similar shift in sensibilities has forever distanced us from the Elizabethan mode of men playing women on the stage, Callow says. “When Mark Rylance plays Olivia (in “Twelfth Night”), it’s not the same thing as the convention Shakespeare knew, in which prepubescent boys played these intense love scenes with adult male actors. We’ll never know what that was like. We’ve blocked ourselves off from it.

“But it does explain something about the women in Shakespeare. Because they were being played by boys, even if very bright boys, Shakespeare had to write the psychology into the parts so they couldn’t fail. They are vividly, brilliantly written: Just do them.”

If Ophelia comes within that embrace, so – in Callow’s view — does Hamlet, whom the actor scarcely touches in “Being Shakespeare.” (It’s the ghost of Hamlet’s father that gets attention.) “Hamlet is the first and still greatest representation of the mind thinking in the moment,” says Callow. “The directness of it, the spontaneity of it, the liveliness are utterly thrilling. You don’t have to play Hamlet. Just say it and it comes to life. Just connect your synapses to Hamlet’s and it will take you on the journey.”

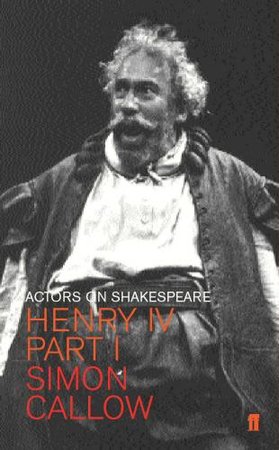

Of all the characters – historical, comical, tragical, tragical-comical or otherwise – who inhabit Shakespeare’s world, the one with whom Callow identifies most personally is Falstaff, the fat knight and prevaricating reprobate who carouses with Prince Hal in the two plays of “Henry IV.”

Of all the characters – historical, comical, tragical, tragical-comical or otherwise – who inhabit Shakespeare’s world, the one with whom Callow identifies most personally is Falstaff, the fat knight and prevaricating reprobate who carouses with Prince Hal in the two plays of “Henry IV.”

“Falstaff is home for me. I’ve played him twice and intend to play him again,” says the actor, who has also written extensively on that rotund subject. “I just feel utterly at home in the landscape of that man. He is Shakespeare’s greatest character, every word sublime genius – epic but also thoroughly real, and deeply pagan. I love the sense of Falstaff as fallen monarch. He really believes himself to be Henry IV’s equal.

“I’m also very fond of Mamillius (the young son of King Leontes and Hermione in ‘The Winter’s Tale’). There’s a realistic simplicity in his mother saying, ‘Come on, sit down, tell us a tale – and do your best to frighten us.’ It’s like overhearing somebody in the flat next door.”

This, says Callow, is the natural world in which “Being Shakespeare” tries to root the Bard of Avon: “In his father’s workshop making gloves, in the theater, accumulating property, getting his coat of arms and — right at the end in retirement — his hopelessness, the sense that he has been passed by.”

And thus Callow’s portrait, this ample sketch, reflects the lifetime immersions of an actor and a scholar. But not for a moment, says the actor, could he actually imagine himself being this genius Shakespeare.

“It’s almost impossible to put yourself in Shakespeare’s mind. Shakespeare was like Mozart,” says Callow, who played the title role of the composer in the world premiere stage production of Peter Schaffer’s “Amadeus” in 1979. “They got so little credit in their world. They were just doing a job, even if they knew they were better at it than anybody else. There was not this concept of the artist, the towering genius.

“During rehearsals for ‘Amadeus,’ I was focusing on the infantile side of Mozart, and his obsession with shit. Peter Schaffer gave me a note saying I must never forget this was the same Mozart who wrote the Overture to ‘The Marriage of Figaro.’ That was Shakespeare, a man working to feed his family and buy a nice house, but also a man through whom all that incredible work was pouring at white heat.”

Related Links:

- Simon Callow’s published works include an introduction to “Henry IV,” Parts I and II, the plays that immortalize the character Falstaff: Find them here and here.

- More on Shakespeare from playwright Jonathan Bate: Read an excerpt from “The Soul of the Age”

- Actors Simon Callow and Stephen Fry share the stage to talk about the theater profession: Watch it on YouTube

- Callow recites the seven ages of man entire: Click here to watch this episode from WTTW’s Chicago Tonight

- Performance location, dates and times: Go to TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: "Amadeus", "Being Shakespeare", Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Jonathan Bate, Mozart, Peter Schaffer, Shakespeare, Simon Callow