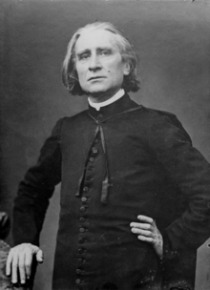

CSO marks Liszt bicentenary with an epic and a romp

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Riccardo Muti, conductor; Michele Campanella, piano. Through Oct. 4, 2011, at Orchestra Hall. *****

By Lawrence B. Johnson

A hundred years ago, when the still-youthful Chicago Symphony played under the baton of Frederick Stock, the orchestra celebrated the centenary of Franz Liszt’s birth in 1811 by programming two of the composer’s signature masterpieces: the First Piano Concerto and the epic “Faust Symphony.”

While most of us probably missed that one, it could hardly have outshone its replication Friday night – in observance of Liszt’s second hundred years – by the CSO under its tenth music director, Riccardo Muti.

As popular as the First Piano Concerto has remained, so the “Faust Symphony” has faded into near obscurity. All the more wonderful to revisit this 73-minute operatic tone poem in a performance of such finesse, rhetorical power and theatrical flair.

Inspired by Goethe’s majestic poem about the world-weary scholar who commits his soul to the devil in exchange for a chance to really live, specifically to party with the innocent Gretchen, Liszt’s symphony unfolds in three movements that characterize, respectively, Faust, Gretchen and the demonic Mephistopheles. An extended coda to the final section, virtually another movement, introduces a male chorus and solo tenor to sing the last eight lines from Goethe’s “Faust, Part II,” a commentary on the transitory nature of all things and the redemptive promise embodied in womanhood.

But before any words are uttered, Liszt creates in the three symphonic tableaux a sequence of quasi-narrative portraits more evocative in their interwoven scheme than words could ever manage. And once again, Muti the opera maestro draws from his adroit band a performance that feels almost verbal and yet achieves the transcendence beyond consciousness that is tone painting.

A virile imagining of Faust, led by lustrous string playing and soaring brasses, gave way to a gentle, lyrical likeness of Gretchen, the movement that forms not just the centerpiece but the soul of this work. Here, at Muti’s carefully modulated tempos, the CSO woodwinds put on a spectacular display of subdued virtuosity. The playing sang and sparkled. It was a love song, buoyed on radiant strings.

For sheer brilliance, however, it was Liszt’s grand scherzo invoking Mephisto that brought the CSO to fever pitch. Here Liszt owes perhaps a double debt to Berlioz, first in the obvious example of the demonic finale of the “Symphonie Fantastique” but no less to the skittering rhythms, gossamer textures and ironic tone of the Queen Mab scherzo from the “Roméo et Juliette” symphony.

Muti filled the scherzo with a pulsing energy, a rhythmic madness that turned this portrait – with its borrowed themes

from the earlier movements – into an image of the dark side as a warped reflection of the ill-starred Faust and Gretchen. It was also a field day – in a really wild field – for every section of the CSO as the music careened and leaped and winked.

And still there were was the beatific sound of the human voice to come – from singers still nowhere in sight. Per Liszt’s specific stage directions, the men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus slowed paraded into view, like holy pilgrims, at a lull near the scherzo’s end – with tenor Eric Cutler materializing in the balcony behind the orchestra.

Thus they declaimed the lines from Goethe’s “Faust” that Mahler would use again in the finale of his Eighth Symphony half a century later, beginning: “Alles vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis” – everything transitory is only approximation. The sound of the men’s voices was hair-raising in its crisp virility and ringing affirmation. Cutler’s sweet tenor was that of the archangel presiding over redemption, the corona on a gift the audience received with shouts of gratitude.

Speaking of fiends, pianist Michele Campanella tamed one in style with his devil-may-care romp through Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat. The piece is so much fun, and so hard. But the veteran Campanella – who is president of the Società Liszt, the Italian chapter of the American Liszt Society – tossed it off with imposing strength, shimmering runs and an uflappable élan. Muti and company supported him in the spirit of Liszt’s flamboyant design: chamber music splashed large.

Riccardo Muti photo credit: Todd Rosenberg.

Tags: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Franz Liszt, Frederick Stock, Michele Campanella, Riccardo Muti, Rudolph Ganz