Capping second CSO season with Bruckner, Muti pledges Austrian-accented 6th Symphony

Exclusive Interview: Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Riccardo Muti shares his devotion to Bruckner. The Italian maestro leads the Sixth Symphony in concerts June 22-24 at Orchestra Hall.

Exclusive Interview: Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Riccardo Muti shares his devotion to Bruckner. The Italian maestro leads the Sixth Symphony in concerts June 22-24 at Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

When conductor Riccardo Muti recorded Bruckner’s Symphony No. 6 in A Major with the Berlin Philharmonic 25 years ago, he came to the task steeped in the Bruckner tradition of the Vienna Philharmonic – a distinctively Austrian way of looking at this thoroughly Austrian Late-Romantic composer.

Now, to close out his second season as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Muti will lead performances of the Bruckner Sixth on June 22-24, once more urging his musicians to find the true composer in Bruckner’s formative connection to the natural world of his youth.

“I believe many times Bruckner is performed like a German composer in the wrong-headed concept that German means heavy,” says Muti during a conversation in his office at Symphony Center. “Heavy doesn’t mean deep. Sometimes heavy just means heavy.

“I believe many times Bruckner is performed like a German composer in the wrong-headed concept that German means heavy,” says Muti during a conversation in his office at Symphony Center. “Heavy doesn’t mean deep. Sometimes heavy just means heavy.

“The Bruckner tradition I learned from the Viennese shows a kindness in his music. Each of his symphonies expresses a gentle way of offering music to Nature, to God. As a boy growing up in Linz, Bruckner walked from his house to school through a woods. You can feel this natural world in his music – not in a rustic way, but in a spiritual sense. It is grandiose, but also melancholy.

“I adore Bruckner. When you conduct a Bruckner symphony, you start a spiritual voyage. He brings you by the hand to some beautiful, sometimes tragic, aspects of the soul.”

The conductor recalled visiting the Austrian town of St. Florian, near Linz, where Bruckner served as church organist. He is buried in the church.

“I was so moved to see this fantastic church and the huge instrument where this small man would create these incredible, enormous sonorities. I had the privilege to go into the crypt, where his coffin can be seen. It is a small coffin, placed exactly under the organ. It was so touching to see this poor, small coffin that contains the remains of a giant of music who created these amazing symphonies.”

“I was so moved to see this fantastic church and the huge instrument where this small man would create these incredible, enormous sonorities. I had the privilege to go into the crypt, where his coffin can be seen. It is a small coffin, placed exactly under the organ. It was so touching to see this poor, small coffin that contains the remains of a giant of music who created these amazing symphonies.”

In turning to the Sixth, Muti once again takes up what is perhaps the least performed of Bruckner’s nine numbered symphonies. Composed between 1879 and 1881, the nearly hour-long work boasts a spectacular, albeit technically imposing opening movement and what Muti describes as the most glorious of the composer’s many sublime adagios. So why has this splendid edifice earned the sobriquet of Brucknerian step-child?

“Possibly laziness,” replies the conductor after a moment, referring to the effort required for this elusive work. “I really don’t know. Maybe the difficulty of the first movement with its irregular rhythms. And the last movement is the weakest part of the Sixth. It’s beautiful but too fragmented, too tentative. It’s like so many of Bruckner’s last movements: It starts well, but it seems he doesn’t find a way to develop his ideas and find a conclusion. In this case, his solution is to return to elements of the opening movement. To make it work, you must know exactly what you want and how to manage it.”

“Possibly laziness,” replies the conductor after a moment, referring to the effort required for this elusive work. “I really don’t know. Maybe the difficulty of the first movement with its irregular rhythms. And the last movement is the weakest part of the Sixth. It’s beautiful but too fragmented, too tentative. It’s like so many of Bruckner’s last movements: It starts well, but it seems he doesn’t find a way to develop his ideas and find a conclusion. In this case, his solution is to return to elements of the opening movement. To make it work, you must know exactly what you want and how to manage it.”

But Muti attaches no such qualifiers to the second-movement Adagio, which he calls not only the greatest of Bruckner’s slow movements but indeed some of the most profound music ever written.

“It makes a beautiful beginning, then in the middle comes a sort of funeral march,” he says, illustrating at some length in a soft vocalise. “It is full of pain. The conclusion of the Adagio is breathtaking. You feel you don’t want to hear anything else after that.”

Admitting that Bruckner is a tricky musical personality to comprehend, Muti says the common mistake is to regard him as a boring man who spent his time at confession in church.

“He was very human, and it is wrong to approach his symphonies as if they were written by a saint. Listen to his scherzos. They are very much of the earth. We need to get away from the cliché of the Bruckner who speaks to God every day.

“In Italy, when I was a boy at school, Verdi was presented to us untouchable, one of the fathers, a figure on a pedestal. He was almost Saint Verdi. I later discovered he was a very normal person. It is the same with Bruckner. People like to mold personalities for their convenience, but that is not realistic.”

“In Italy, when I was a boy at school, Verdi was presented to us untouchable, one of the fathers, a figure on a pedestal. He was almost Saint Verdi. I later discovered he was a very normal person. It is the same with Bruckner. People like to mold personalities for their convenience, but that is not realistic.”

By the same token, says the maestro, Bruckner’s epic symphonies cannot be condensed to suit a preference for brevity.

“The long arch is Bruckner’s musical personality. If you shortened his symphonies, you wouldn’t have Bruckner any more. For example, when he insists on repeating certain rhythmic or melodic elements, it is always for a deep reason. It wasn’t that he didn’t know what he was doing. The repeated elements are cosmic extensions. They produce an atmosphere that is metaphysical, something that takes us far away.”

To a degree, says Muti, Bruckner’s motivic iterations also can be found in Beethoven – in the four-note cell from which the entire Fifth Symphony is developed. But Beethoven was far more concise.

“That’s because Beethoven was more interested in form, in the classical architecture,” says Muti. “Bruckner, like Mahler, breaks down the walls of classical form. And already in Bruckner, chromatic harmony is being pushed toward its limits – even in small, quick notes, in the details. To Bruckner, details are very important. They are not just colors, but substance. Every little note contributes to an entire world. This is his landscape. It’s like a magic garden.”

“That’s because Beethoven was more interested in form, in the classical architecture,” says Muti. “Bruckner, like Mahler, breaks down the walls of classical form. And already in Bruckner, chromatic harmony is being pushed toward its limits – even in small, quick notes, in the details. To Bruckner, details are very important. They are not just colors, but substance. Every little note contributes to an entire world. This is his landscape. It’s like a magic garden.”

CODA:

Muti intends to make his way through the Bruckner symphonic canon with the CSO, and to record the complete cycle.

“That would be fantastic,” he says. “I think this is a very good orchestra for Bruckner.”

And while on the subject of recording, the maestro volunteered that he’d like to make a third run through the complete Beethoven symphonies, which he previously recorded with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the orchestra of Milan’s La Scala Opera.

“I would like to create another document of my interpretation of the Beethoven symphonies,” says Muti. “It might be interesting for those who are interested in what I do.”

Related Links:

- CSO Bruckner concert performance location, dates and times: Details at the Chicago Symphony

- CSO plans 2013 Asia tour with Muti: Details at Chicago On the Aisle

- Exclusive interview with Muti on plans to stretch the CSO: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

- Exclusive interview with Muti on the conductor’s art: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

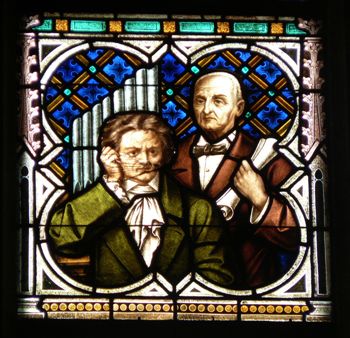

- The Beethoven-Bruckner portrait, above, is part of a vast array of stained glass in the Linz New Cathedral (Neuer Dom or Maria-Empfängnis-Dom): See more images here

- Riccardo Muti’s Bruckner’s recordings: Visit abruckner.com

Photo captions and credits: Home page and top: Riccardo Muti, music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Photo by Todd Rosenberg) Anton Bruckner wearing the Order of Franz Joseph awarded in 1886, portrait by Josef Büche (1893). Bruckner looks over Wagner’s shoulder in stained glass at the New Cathedral in Linz. Conductor Riccardo Muti. (Photo by Todd Rosenberg) CD cover for EMI’s reissue of Riccardo Muti conducting Bruckner’s Fourth and Sixth Symphonies with the Berlin Philharmonic, recorded in the mid-1980s. Richard Wagner, left, greets Bruckner in Bayreuth, 1873 silhouette by Otto Böhler. Below: Bruckner statue in the Stadtpark, Vienna.

Tags: Bruckner, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Linz Neuer Dom, Linz New Cathedral, Riccardo Muti

1 Pingbacks »