Marriage of true minds: Chicago Shakespeare brings the Bard to Chicago Symphony’s party

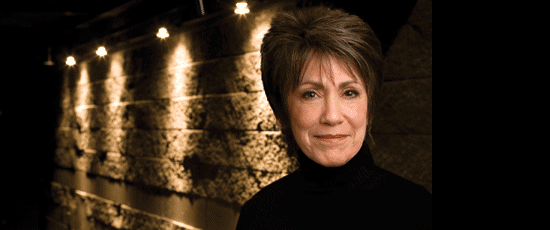

Preview: Barbara Gaines directs actors from Chicago Shakespeare Theater in concerts Jan. 5-14 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Mark Elder, featuring music inspired by the Bard.

Preview: Barbara Gaines directs actors from Chicago Shakespeare Theater in concerts Jan. 5-14 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Mark Elder, featuring music inspired by the Bard.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

For Barbara Gaines, the Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s venerable artistic director, to witness Shakespeare played well is to hear music. The French Romantic composer Hector Berlioz felt exactly the same.

Theater director and composer meet – in spirit at least – on the stage of Orchestra Hall, Jan. 5-7, when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra offers the first of two programs on the theme of Shakespeare in music.

Theater director and composer meet – in spirit at least – on the stage of Orchestra Hall, Jan. 5-7, when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra offers the first of two programs on the theme of Shakespeare in music.

The CSO’s mini festival, which continues Jan. 12-14, is the brainchild of British conductor Sir Mark Elder, who will preside over Berlioz and the Bard before revisiting Shakespeare through the music of Sir Edward Elgar and Tchaikovsky.

Both programs will spotlight actors from Chicago Shakespeare Theater reading scenes from the plays to set up the purely orchestral works at hand. The two plays in question reflect the singular range of Shakespeare’s portraiture, from love at its most tender to life at its most lusty.

Up first will be “Romeo and Juliet,” which so moved Berlioz when he saw it in 1827 – in English yet – that he translated the work into a dramatic symphony complete with chorus.

Up first will be “Romeo and Juliet,” which so moved Berlioz when he saw it in 1827 – in English yet – that he translated the work into a dramatic symphony complete with chorus.

The Juliet of that production, 27-year-old Harriet Smithson, also dazzled the 24-year-old composer, who began a quest to win her that indeed ended in victory.

They were married in 1833. Alas, their romantic bubble burst six years later, but then things didn’t end so well for Romeo and Juliet, either.

Exactly how R&J come to their respective ends is much to the point of the CSO’s performance and the readings that will preface it. The “Romeo” that Berlioz saw in Paris was not the version we see today but rather an “improved” account by David Garrick, the most celebrated Shakespearean actor of the 18th century. And it was specifically that version that Berlioz endeavored to recall in his symphony.

Exactly how R&J come to their respective ends is much to the point of the CSO’s performance and the readings that will preface it. The “Romeo” that Berlioz saw in Paris was not the version we see today but rather an “improved” account by David Garrick, the most celebrated Shakespearean actor of the 18th century. And it was specifically that version that Berlioz endeavored to recall in his symphony.

“If Berlioz didn’t understand the words, he certainly understood the emotion of Garrick’s text,” says Elder. “He clearly appreciated the elaborate moment Garrick gives them together. Unlike the Shakespeare most of us know, Garrick’s version has the two lovers engage in extended dialogue in the tomb scene. It was Berlioz’s avowed intention to recreate in music their exact words. I must say that when I read Garrick’s tomb scene, my appreciation of Berlioz’s setting improved by 500 percent.”

Portraying the star-crossed lovers will be CST ensemble members Brendan Marshall-Rashid and Susan Shunk. Though they won’t be costumed and physical interaction may be limited, like all actors these two will rely on an expert observer to make sure the pulse and expression of the language are true. That’s where Gaines comes in, doing what she’s done a thousand times as a director.

Portraying the star-crossed lovers will be CST ensemble members Brendan Marshall-Rashid and Susan Shunk. Though they won’t be costumed and physical interaction may be limited, like all actors these two will rely on an expert observer to make sure the pulse and expression of the language are true. That’s where Gaines comes in, doing what she’s done a thousand times as a director.

“Berlioz’s music is so poignant, it’s almost as if Shakespeare were composing it,” says Gaines. “But the play itself is so musical, so dynamic. Everyone remembers the first time they fell in love. Our hearts are all the same in that way. ‘Romeo and Juliet’ makes us all one. It’s about the human heart — the walking on air, the terror, the extremities of emotion, the incredible enthusiasm, the obsession that love brings.

“That’s the brilliance and genius of Shakespeare, these huge themes presented and communicated in universally profound ways.”

Besides music evoking the tomb scene, the CSO will play Berlioz’s gossamer Queen Mab scherzo. Elder said he might have included the radiant “scène d’amour,” surely the most famous and arguably the greatest music from the symphony, but decided against it out of concern for the concert’s length.

There is another “Romeo and Juliet” connection on this program: Berlioz’s pictorial concerto for viola “Harold in Italy,” with Lawrence Power as soloist. It was the great violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini who asked Berlioz to write the work. When Berlioz’s sketches seemed to downplay the viola’s role, Paganini lost interest; but upon hearing the work performed, he summarily awarded Berlioz 20,000 francs for so great an achievement – funds that allowed the composer to suspend his livelihood as a critic and devote himself wholly to the creation of “Romeo and Juliet.”

There is another “Romeo and Juliet” connection on this program: Berlioz’s pictorial concerto for viola “Harold in Italy,” with Lawrence Power as soloist. It was the great violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini who asked Berlioz to write the work. When Berlioz’s sketches seemed to downplay the viola’s role, Paganini lost interest; but upon hearing the work performed, he summarily awarded Berlioz 20,000 francs for so great an achievement – funds that allowed the composer to suspend his livelihood as a critic and devote himself wholly to the creation of “Romeo and Juliet.”

The CSO’s second Shakespeare program, Jan. 12-14, focuses on one of the Bard’s most vivid and endearing characters, Sir John Falstaff, the roguish fat knight of “Henry IV,” parts 1 and 2. But not, as Elder stresses, the almost buffoonish Falstaff that Shakespeare subsequently drew for “The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

“That caricature was a sop to public taste,” says Elder of the latter Sir John. “Elgar was a master symphonic writer and his ‘Falstaff’ is a great piece of program music, a detailed musical narrative that extends over one grand arch about 35 minutes long. It moves at a brisk pace and gives us an enormous amount to react to as it goes by.”

Listeners will be doubly abetted in tracking the music – first by readings from the two “Henry IV” plays by Chicago Shakespeare ensemble member Greg Vinkler, then by scene summaries projected on a screen at the beginning of each section of Elgar’s symphonic portrait.

Listeners will be doubly abetted in tracking the music – first by readings from the two “Henry IV” plays by Chicago Shakespeare ensemble member Greg Vinkler, then by scene summaries projected on a screen at the beginning of each section of Elgar’s symphonic portrait.

“This is the Falstaff of rumbustious energy and great wit, a man given to fibbing and devoted to the pleasures of the flesh – wine, food, women,” says Elder. “He is pretentiously preposterous. And Elgar nails each of those facets one after another.”

As the embodiment of Falstaff, Vinkler brings imposing credentials to the party. He has played Sir John in four different CST productions, including a double run in 2006 when the Chicago staging was remounted in London at the invitation of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Here he will revisit some of Falstaff’s best known speeches, including his exegesis on honor, his paean to the inebriating delights of sack, and the dissembling monologue “A plague of all cowards” in which he deflects the truth about a recent encounter that went badly. In the end, as it comes bitterly to Falstaff, Vinkler will switch to the voice of newly crowned King Henry V, who turns on his old carousing pal in a shockingly severe dismissal: “I know thee not, old man.”

“Greg is so brilliant,” says Gaines, who once again will be coaching her star Falstaff, “and Sir John is one of the most complete and colorful human beings ever to be written. He is larger than life, complex, charismatic – someone with no conscience but a great sense of humor, someone who would leave you on the battlefield if he was afraid for himself.

“There was never a wittier soul, ever. Everyone I know would want to have a beer with Falstaff.”

Related links:

- Location, dates and times: Chicago Symphony Orchestra website

- Six plays touching upon Shakespeare remain in the 2011-2012 CST season: Chicago Shakespeare Theater website

Tags: Berlioz, Brendan Marshall-Rashid, Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Chicago Symphony, Elgar, Greg Vinkler, Harriet Smithson, Lawrence Power, Mark Elder, Paganini, Susan Shunk