At Cliburn competition finals, blazing talent

ruled as world politics hovered in the wings

From 30 competitors, these were the Cliburn’s final six: Top left, gold medalist Yunchan Lim, 18, South Korea. Clockwise from top right, silver medalist Anna Geniushene, 31 (Russia); bronze medalist Dmytro Choni, 28 (Ukraine) ; Clayton Stephenson, 23 (U.S.); Ilya Shmukler, 27 (Russia); Uladzislaw Khandohi, 20 (Belarus) – Photos courtesy Cliburn Competition

Report: Six pianists from five countries made it to the finals at the 16th Van Cliburn international faceoff. Here’s how it all played out.

By Jennifer Melick

FORT WORTH, Tex. – Mid-June heat was on in the entire middle third of the country, all the way from Chicago, where temperatures hit the upper 90s, to Fort Worth, with daytime highs in the triple digits. The heat was on in Bass Performance Hall as well, as 30 pianists from around the world competed at the 16th quadrennial Van Cliburn International Piano Competition.

There was an unusual amount of media coverage this year, after Cliburn CEO Jacques Marquis decided in March to admit Russian competitors, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, even as some music competitions initially opted to ban them. (Of the latter group, many, including this year’s Honens and Dublin piano competitions, later reversed those decisions.) The total number of pianists who applied to perform in the Cliburn competition this year was 388, an all-time high.

What no one back in March could have predicted was that when that number got whittled down to six finalists, the group would include two Russians (neither currently living in their home country) and a Ukrainian, as well as one apiece from the U.S., Belarus and South Korea. Security was stepped up in March due to concerns about possible protests or harassment of Russian competitors; a sniffer dog was present at every round of the competition that I attended. High stakes, indeed.

There was no sign of protests during the competition. But there were extra cheers from the crowd for Dmytro Choni, a 28-year-old Ukrainian pianist from Kyiv, currently based in Austria. “We’re rooting for the Ukrainian!” enthused one audience member outside the concert hall after Choni’s performance of Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3. Several minutes later, Choni emerged from Bass (with his Cliburn host family) to squeals from a small group of admirers who asked for selfies, which he happily provided.

In the New York Times, Choni described the war as “a tragedy, what’s happening now. I’m trying to stay focused on the music.” He did not want to speak about it any further during the competition, preferring, again, to just “be myself, share my vision of this music” with the audience, as he said at a June 16 press conference. Cliburn officials and jury members were at pains to emphasize that they do not judge the competitors on anything except their musical performances. The jury was strictly forbidden to discuss competitors’ performances among themselves.

To state the obvious, those rules didn’t apply to the audience. Any of the 30 pianists chosen to perform in person at the Cliburn has the potential for a major career, but it surely didn’t hurt to have the kind of support Choni received, inside and outside the concert hall. Marin Alsop, chief conductor of the Ravinia Festival, chaired this year’s jury of nine distinguished pianists, and she conducted the pianists in their concerto performances with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra.

It’s quite something to behold how the city of Fort Worth goes all out for the Cliburn’s flagship competition, which is held every four years (this year’s edition was delayed one year due to the pandemic). The streets are festooned in Cliburn banners. The pavilion at one corner of Sundance Square – the big outdoor plaza just down the block from the concert hall – announced the competition’s 60th year in huge lettering on all four sides of the building. Many businesses decorated their storefronts with signage themed to the competition as well.

The competition is streamed live online at Cliburn’s website and at medici.tv. When I stopped in a shop near Sundance Square; the proprietor told me she had been viewing all the concerts, even during a recent visit to Greece. She was excited about Clayton Stephenson, a student in the double-degree program at New England Conservatory and Harvard University who was the only American to make it into the final competition round.

In 2017, the Cliburn for the first time simulcast the final two competition concerts on a large screen set up in Sundance Square; this year the tradition continued on the final weekend. On a sweltering evening, the outdoor crowd strolled, chatted quietly, dozed, watched intently. One couple briefly danced a tango; a two-year-old boy aimed his imaginary finger-pistol at people coming out of a nearby Starbucks – this is Texas, after all. This year, for the first time, were added daytime family events in the square on Saturday: kids’ piano concerts in the pavilion, electronic pianos to walk on, face-painting, balloons, an opportunity to “Conduct-A-Quartet” under the square’s giant sun umbrellas.

.

Van Cliburn is almost a physical presence during the competition. Everyone you meet seems to have a personal story about the time they met this legendary Texan – Harvey Lavan “Van” Cliburn Jr., 1934-2013 – who founded a piano competition in his home state in 1962. When people find out you are in Fort Worth for the competition, they offer, unprompted, their stories of being invited to watch a DVD with him of one of his performances, going to a lavish party at his home, how he took time to greet every single person who wanted to meet him.

If you know anything at all about classical music, you already know that at age 23, Cliburn won the inaugural Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in the Soviet Union in 1958, at the height of the Cold War, when most people assumed the medal would go to a Russian pianist. As Marin Alsop noted at the competition, it was “an incredible moment when he won the gold medal—a symbol for American possibility.” Cliburn received the only ticker-tape parade in New York City ever given for a classical musician and had a huge performing and recording career, becoming the world’s highest-paid musician at one point, and forever was one of classical music’s most recognized names.

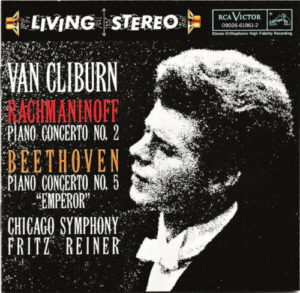

In Chicago, he played in Grant Park after winning the Tchaikovsky competition in 1958. With the Chicago Symphony Orchestra alone, he recorded Beethoven’s Piano Concerto Nos. 4 and 5, Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 2, and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2, all led by Fritz Reiner; he recorded MacDowell’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the CSO led by Walter Hendl. But Texas was where he made his lasting mark.

The inherent drama of a piano competition cannot be denied. Unlike a concert, someone will win, and someone else will not. So, how did this one go? In alphabetical order by last name, let’s start with Dmytro Choni, a slight young man with light brown hair, wearing a dark grey suit, who chose for his first concerto performance Prokofiev 3. He brought high energy, some meat to the tone, and an exceptionally clean technique. The sound popped out over the orchestra. The first movement was fast, but not hair-raising, with an appropriately impish march-like section. In the second movement, he brought exceptional clarity to the inner harmonies. The unsettling middle section became almost unbearably creepy, slow, and tense. In the third movement, he produced dramatic low rumblings and the final tight clusters of notes were thrilling. The audience yelled its approval at the end. He appeared to be a big audience favorite.

Two days later, Choni’s second concerto – Beethoven 3 – didn’t quite attain the level of the Prokofiev. In the first movement, he displayed the rhythmic propulsion that is so essential to Beethoven, and the double trills in the cadenza were lost, forlorn, beautiful. He brought more melancholy to the second movement, where thirds sounded sweet and sad; the cadenza meandered off, and once again there was a feeling of great sorrow, of being lost. He received a bouquet of sunflowers – the national flower of Ukraine – at the end. (Other performers also received flowers, though without so much heavy symbolism.)

Anna Geniushene, a 31-year-old Russian from Moscow, left her home after the start of the war in Ukraine and resettled in Vilnius, Lithuania. She performed in black, flowy pants and blouse, with salmon pink shoes. This was less a fashion statement than a reflection of the fact that she is 6 months pregnant with her second child.

Her first concerto performance was Beethoven 1. In the first movement, she brought out the syncopation, the off-beats. She produced a singing tone. In the cadenza there was a contained ferocity. In quieter sections, the the room focused in: You could have heard the proverbial pin drop. Often she seemed in her own world, and played with her head down. In the second movement, her velvety touch was especially effective in piano passages. Her soft trills sounded like birds. The third movement was joyful, not aggressive, though occasionally I wished she would go for a little more.

The Beethoven didn’t quite prepare me for her next concerto, Tchaikovsky 1. She ripped into the piano, displaying exceptional power. She grabbed notes like a bear clawing at the ground. She looked completely relaxed, not one bit nervous. The use of pedal was heavy. The growling lower passages were splendid. At the end of the movement, someone in the audience yelled “Whoa!” Up until that point the audience had been almost completely silent, with all the performers. The second movement trills were spectacular, and she took the third movement thrillingly fast. She is a refined, mature artist clearly ready for the next stage of her career. Also, she said in a press conference at the end of the competition, it’s not easy playing all those octaves “with a big belly,” as she put it.

It was hard to know what to make of Uladzislaw Khandohi, a slender, serious 20-year-old pianist from Belarus who barely smiled during the competition. He seemed exceptionally young. He performed a bit hunched down, reminiscent of Glenn Gould at the keyboard. The best part of Khandohi’s first concerto performance, Rachmaninoff 2, was the second movement, which felt aching, inevitable. Otherwise, there wasn’t much that made it stand out.

His second concerto, Chopin 1, was much better. Khandohi has the dreamy, romantic temperament down. He often played with his eyes closed, accompanied sometimes by distracting mouth movements. He and the orchestra did not seem to interact much in the first movement. The second movement was intensely sweet; the interplay with the bassoon was exquisite. He smiled rapturously. It was a magical effect, like watching a beautiful butterfly flying overhead. I could have listened to him play this way for hours. In the third movement, he looked much more relaxed, and interacted more closely with the orchestra. It is possible he was overwhelmed by the situation. He will have more chances, and he’s an intriguing artist that I’d like to hear again in a few years’ time, maybe in a less high-pressure situation.

South Korean pianist Yuncham Lim, a diminutive 18-year-old with a mop of hair a la early Beatles, played Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto with a sweet tone and gentle approach. The hall was completely silent in the first-movement cadenza: He has refined the art of drawing you in by making a pianissimo dramatic. He took a very slow tempo in the second movement, almost losing direction or any sense of bar lines, and the cadenza got bogged down.

Lim’s second concerto performance, Rachmaninoff, was simply astonishing, and could not have been predicted from the Beethoven. He smiled at the conductor and orchestra, and then began the simple opening melody in a way that seemed completely organic, coming from deep within. The arc of the phrases was crystal-clear. After the quiet opening, he displayed an unexpectedly thrilling wildness and abandon. In the first-movement cadenza, he sparkled in the upper reaches, and the pedaling was effective, allowing the melodic tracery to come out. He produced an exquisite sighing effect in those three pairs of chords that come about eleven minutes into the first movement.

In the second movement, the dazzling opening trill seemed to come out of nowhere. In heavier, more passionate phrases you could still hear the inner voices clearly. In the third movement, there was smoothness and lyric sweetness, still clarity, not too much pedal. In the really big moments there was ferocity – Lim almost lifted up off the bench. His hair swished and bounced. Throughout, you felt and saw that the orchestra was right with him. It was the most unified of all the concerto performances. The audience’s standing ovation was unison and immediate, and the applause was loud and long. It was a performance that will be remembered long afterward by anyone who was there.

Russian competitor Ilya Shmukler, currently living in the U.S. where he studies with former Cliburn gold medalist Stanislav Ioudenitch, was another finalist who performed Rachmaninoff 3 during the concerto round. He has a big presence that makes you sit up the minute he walks onstage. He is a beast of a pianist, an intensely physical performer with a muscular tone, and sustained notes that flow effortlessly out of the piano: the classic Russian school. It’s fiery, tragic, sometimes a bit messy. You wonder: Will the train stay on the tracks, or will it fly off? But it’s undeniably exciting.

The third movement felt improvised on the spot. Before the last wild phrase, as Shmukler lifted his hands to play, you almost wanted to yell, “Hold it together, Ilya!” At the end, he looked spent. He might have pushed himself farther than he should have.

I viewed his second concerto performance, the Grieg, outdoors at the large-screen plaza simulcast, which allowed a view of him in close-up that is not possible in the concert hall. Marin Alsop was smiling. Shmukler was in the moment, with sweat dripping, actually spewing, in multiple directions. His hair stuck to his face. The first movement cadenza was ferocious. He attacked the piano in the third movement, his face animated. Pianist and orchestra played well together, and the applause at the end was huge.

American pianist Clayton Stephenson, a New Yorker, selected Gershwin’s Concerto in F for his first concerto performance. He looked relaxed and happy to be onstage, and had an easy rapport with the orchestra, conductor, and audience. It was fun to watch him sit-dancing on the piano bench before his first entrance, during the orchestral introduction. When he did launch into the music, his rhythm and syncopation were spot-on. He played within himself and did not push one bit.

He got upstaged briefly in the second movement during an exceptionally sleek, lazy opening trumpet solo. In the second movement’s free-ranging cadenza you still always felt the piano’s underlying rhythm. In dramatic sections, Stephenson used his left leg to briefly jump vertically off the bench. His off-beat grabs of notes in the third movement were especially effective. It’s great to watch an artist in tune with the musicians around him, and seemingly not be “competing,” but just enjoying the music.

Stephenson’s next concerto, another Rachmaninoff 3, was not quite as strong as the Gershwin despite many lovely moments. The opening melody was gentle and melancholy. The first-movement cadenza had an intriguing architectural quality, and post-cadenza there was a tight interplay with flute and oboe and clarinet and horn. You heard in his playing how well he was listening to the orchestra. The second movement was big but not uncontrolled; he was very effective in impish passages, and precise in quiet passages. The big passages, that deep Rachmaninoff ache, sometimes were missing. I would love to hear him perform Bartók.

After all the competitors were finished performing on Saturday, there was a two-hour wait for the jury to choose the winners. The medals ceremony began with the audience standing as Vadym Kholodenko, winner of the 2013 Cliburn competition, performed the Ukrainian National Anthem. Then it was time to announce the winners. During the final week of the competition, predictions of who would win changed from day to day. Pianists are not robots, their musical level fluctuates, and they are stronger in some works and on some days than others.

In the end, the musician who captures the most hearts is the one who will become the winner, and Yunchan Lim’s Rachmaninoff 3 performance was so spectacular that he became the odd’s-on favorite by the end of the competition. Indeed, he won first place, becoming the Cliburn’s youngest winner ever. After a few bows, he drifted immediately upstage, and Anna Geniushene, who looked shocked and delighted to have won second place, ushered him back toward the spotlight in the front.

Dmytro Choni was smiling from ear to ear at his third-place win. There was a big outdoor party in Sundance Square afterward. The finalists, who looked exhausted and relieved that it was over, signed autographs for fans. Some of the orchestra musicians attended; they too were worn out after a marathon week of rehearsals and performances that on some days added up to 12 hours. All the performances, not just the finals discussed here but the earlier rounds as well, can still be viewed online

.

The competition Cliburn founded has evolved from the days when Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra music director John Giordano first chaired the Cliburn jury in 1973. In his 2020 memoir “Speak Loudly and Carry a Little Stick,” Giordano chronicles the experience in humorous detail. When we spoke in June, he described being thrown in at the last minute as jury chair, and sitting at a table in the concert hall “with a bell and microphone. In those days the repertoire was just ridiculously big, and the competitor would walk out bow and sit down at the keyboard, and I would tell them what to play. They would play, and I would ring the bell, and stop them – off the cuff.”

These days, there are established rules about the many rounds: a preliminary round featuring two solo piano works of the competitor’s choice, plus this year’s commissioned Fanfare Toccata by Stephen Hough; a quarterfinal round (two more solo piano works); two semifinal rounds, one featuring an hour-length recital, the other featuring a Mozart concerto. A recent change since 2017 is that the chamber music round has been eliminated in favor of the final round featuring not one but two piano concertos, performed with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. The chamber music round was something Cliburn strongly supported, and some people were sorry to see it go.

Anna Geniushene already performs a lot of chamber music in her career, and she is not the only pianist who plans to perform that repertoire. It will be interesting to see in future years if this American competition diversifies its list of competition concertos to include more contemporary composers. It would be nice to see more piano concertos by American composers as well. A few names that come immediately to mind are John Corigliano, John Adams, Jessie Montgomery, Gabriel Kahane, and Florence Price.

The established formula for choosing what programs will sell the most tickets may not be applicable to all but the the most traditional audiences, who these days may prefer newer works to the standard Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Chopin, Rachmaninoff. In 2018, Kirill Gerstein was soloist in the well-received world premiere of Thomas Adès’s new concerto, commissioned by and performed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Pianist Yuja Wang and the Los Angeles Philharmonic had a big success in John Adams’s 2019 concerto subtitled “Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?” The LA Phil has proven repeatedly that people will show up eagerly to hear new music; that trust from the audience did not happen overnight but was gained over decades of programs.

What is the point of a competition? At Cliburn, the aim, now as ever, is to give emerging pianists a jump start on their careers, to give them the kind of attention Van Cliburn got when he won the Tchaikovsky competition more than 60 years ago.

Among American pianists to have previously won the competition are Ralph Votapek (1962), André-Michel Schub (1981); and Jon Nakamatsu (1997). Only two women have won first place at the Cliburn: Brazilian Cristina Ortiz in 1969 and Russia’s Olga Kern, who shared first place in 2001 with Stanislav Ioudenitch.

Two pianists who competed in 1981 are among the many non-winners who went on to have significant careers, including Christopher O’Riley, a native of Chicago who hosted the the weekly National Public Radio program From the Top from 1999 to 2018; and finalist Jeffrey Kahane, who has had a significant career as a pianist and conductor. The trajectory of any one pianist cannot be predicted based on a Cliburn medal, but every single finalist gets extra visibility and opportunities – money, mentorship, concert dates – and the chance for a significant career.

Van Cliburn has inspired an army of volunteers to help launch the careers of the best pianists in each generation.

During a jury symposium on June 16, Marin Alsop described this year’s competition as coming at a “portentous moment in our history.” Van Cliburn, she said, “represented so much achievement. Whenever he was interviewed and asked about the politics – we have been obsessively asked about the politics – he always said, ‘it’s all about the music, not about the politics.’ I defer to Van. What an important moment to remember his achievement and what he established here.”

Alsop, and virtually everyone who knew Cliburn, speaks about Cliburn’s personal kindness, his warmth, the deep care he took in guiding the careers of young pianists. The fact that there is an army of hundreds of volunteers who support this massive operation – including a host family for each of the 30 competitors, and loaner Steinway pianos delivered to each of those 30 homes during the two weeks of the competition – reflects the specific, deeply personal vision Cliburn had for the competition.

This year, it was not possible to escape the politics, not even for a few days. In the 1960s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were in the midst of a Cold War. Today, it’s a hot war during Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, the U.S. siding with Ukraine, and tensions between East and West as high as they’ve ever been. But pianists from Russia, Ukraine, America,and elsewhere were able to come together to play music and vie for prizes, visibility, and opportunities to make music and a name for themselves.

And to see that the same kind of hospitality and warm welcome were so much a part of the Cliburn competition experience are still very much in evidence. It was a moment to contemplate our past and our present, and to see how much things have changed – and much they have stayed the same.

Jennifer Melick is managing editor of Symphony Magazine and a frequent contributor to Opera News.