Andrew Davis, gearing up to lead Lyric ‘Ring,’ conducts CSO while cueing ‘Queen of Spades’

Andrew Davis, who will step down as Lyric Opera music director in spring 2021 after two decades, is preparing his second ‘Ring’ cycle with the company. (Dario Acosta)

Interview: Lyric Opera’s music director contemplates Beethoven with Chicago Symphony even as Wagner looms (very) large.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Conductor Andrew Davis, music director of Lyric Opera of Chicago, is taking a time-out from the bit of Wagner he’s preparing over at Lyric – the four-opera, 17-hour “Ring of the Nibelung” – to conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with pianist Paul Lewis in some Beethoven.

Davis’ concerts Jan. 30-Feb. 4 at Orchestra Hall, featuring both Beethoven’s First and Fourth Piano Concertos, play into the orchestra’s year-long celebration of the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

As it happens, 2020 marks a round-numbered anniversary for Davis, as well: 20 years at Lyric’s artistic helm. When the now 76-year-old conductor steps down as Lyric’s music director in May 2021, he can brandish – rather like a repeat Super Bowl champion – not one “Ring” but two.

Huge puppets represent the giants Fasolt and Fafner in the Lyric Opera production of ‘Das Rheingold,’ part one of the ‘Ring.’ (Todd Rosenberg)

Davis’ current undertaking of Wagner’s “Ring” is indeed his second go at this grandest of all grand opera enterprises, both cycles at Lyric, the first brought to a head 15 years ago. He paused backstage at Orchestra Hall to reflect on his late-blooming history with Wagner’s music, his fascination with the monumental “Ring” and the frankly boggling effort required to bring it off.

“Not only did I come to Wagner quite late, but throughout most of my twenties, opera wasn’t really my thing,” Davis said. “I wasn’t really exposed to opera. My family weren’t particularly musical, so a lot of this I did on my own. I saw my first opera when I was 17 or 18.”

Some 15 more years would pass before Davis, by then a successful conductor, would see his first Wagner operas: “Tristan and Isolde” and “Meistersinger.” He was hooked.

Fast-forward nearly three decades. The Lyric wants Davis to take the reins as music director. William Mason, at that time Lyric’s general director, has an idea that gets Davis’ attention.

“I was eager to get my teeth into Wagner, and one of the carrots Mason dangled in front of me was a ‘Ring,’” Davis recalled, beaming again even as he remembered the lure. “In my first season at Lyric we did ‘Dutchman’ and the next year ‘Parsifal,’ then the ‘Ring’ progressively to a complete cycle in 2005.”

Similarly, the current cycle has evolved, opera by opera, over the last four seasons.

The first opera, “Das Rheingold,” is essentially a prelude – the setup, in which the Nibelung Alberich forswears love for a chunk of gold he steals from the Rhinemaidens and forges into an all-powerful ring. Wotan, chief of the gods, tricks Alberich out of the ring only to lose it in payment to two giants for the construction of the great castle Valhalla.

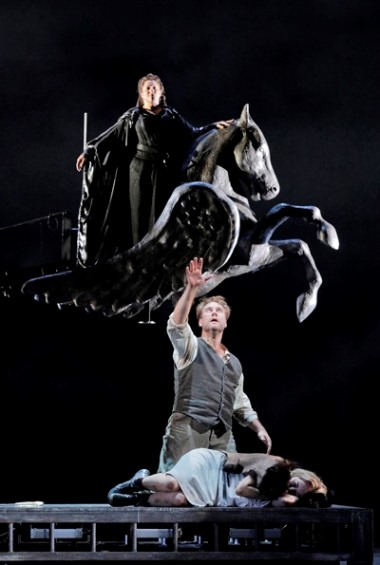

Defying Wotan’s command, airborne warrior-maiden Brünnhilde tries to help the sibling lovers Siegmund and Sieglinde. (Cory Weaver)

In the second opera, “Die Walküre” (the Valkyrie),Wotan’s machinations to recover the ring directly violate the sanctity of marriage when his illicit offspring Siegmund and Sieglinde, separated as children, are reunited as lovers at the expense of Sieglinde’s husband Hunding. Wotan’s wife Fricka, protectress of marriage, intercedes on Hunding’s behalf, resulting in the death of Siegmund – but not before the lovers have conceived a child. Meanwhile, the Valkyrie warrior-maiden Brünnhilde incurs Wotan’s wrath when she acts on his secret wish to protect the siblings and their unborn child. In punishment, Wotan condemns her to sleep on a mountain, surrounded by fire, until some hero might brave the flames to claim her.

The third opera, “Siegfried,” is a sort of dappled comedy about the emergence into manhood of Sieglinde’s child. Not unlike the Greek superhero Achilles, Siegfried is matchless, empowered by his absolute lack of fear and a mighty sword he forges from the shards of the slain Siegmund’s weapon. The comedy touches on Siegfried’s testy relationship with the duplicitous and pathetic Mime, who has raised him with the sole intent of exploiting Siegfried’s prowess to slay a dragon that now possesses the all-powerful ring. Mime plans to kill Siegfried. But the youth prevails and penetrates the magic fire surrounding Brünnhilde to win her.

“The Twilight of the Gods,” or “Götterdämmerung,” concludes the saga in general ruin. Siegfried succumbs to the treachery of a clan of bad characters, who trick him into betraying Brünnhilde. The world of the gods cracks, Siegfried is murdered, Brünnhilde discovers the deception and hurls the ring back to the waiting hands of the Rhinemaidens, Valhalla goes up in flames and Brünnhilde commits herself to the fire. The time of the gods, like Wagner’s epic tetralogy, is done.

“Just in terms of the musical development it represents in Wagner, the ‘Ring’ is extraordinary,” said Davis. “He wrote his own libretto, of course. The whole thing occupied him for more than 25 years. By the time we get to ‘Götterdämmerung,’ with its very sophisticated and rigorous compositional style, the way he was using the orchestra in ‘Rheingold’ seems primitive by comparison.

Fearless Siegfried confronts Fafner, who has assumed the form of a dragon, in Lyric’s production of the third ‘Ring’ opera, ‘Siegfried.’ (Todd Rosenberg)

“The whole thing is done on a scope that no one before Wagner had ever conceived of. And then he lays it all aside, in the middle of ‘Siegfried,’ and says, ‘Oh, I’ll finish this later’ – 10 years later! On his break, he writes ‘Tristan’ and ‘Meistersinger.’ The sheer compositional virtuosity of the ‘Ring’ is astonishing, and so is the fact that, despite Wagner’s huge hiatus, the whole thing hangs together.”

By the same token, bringing the ‘Ring’ to the stage – producing all four operas in the space of a week, three times in as many weeks, as Lyric will do in May – is a hefty, heady achievement.

Davis laughs. “I’ll be 76 this time. I was a mere 61 the first time around – and during that run, I had acupuncture three times a week.”

Before even getting to the first cycle, Davis and company must bring forth its new production of the crowning opera, “Götterdämmerung,” which will have just two performances, April 4 and 11, just ahead of the initial ‘Ring’ sequence.

The physical demands are great on singers and orchestra musicians alike. “You have to be careful about balances, especially in ‘Götterdämmerung,’” Davis said. “There are big, heavily scored moments for both Siegfried and Brünnhilde. My Wagner timings tend to be on the short side. I don’t think we need to solemnize these operas. I mean, at the start of ‘Götterdämmerung,’ you’re waving your arms around and everyone’s been playing for 45 minutes (through an extended preface), you turn the page and it says: Act 1.”

The world of the gods crashes in flames in the ‘Ring’ cycle’s final chapter, ‘Götterdämmerung.’ (Andrew Cioffi)

Length notwithstanding, Davis regards the ‘Ring’ in sum as “the greatest theater there is, in a way. It’s not about the gods, but about us, our taking responsibility in the end. The greatest dramatic moments are the moments of interaction. These (Norse) gods are like the Greek gods, possessing the same, sometimes depressingly similar foibles and weaknesses that we do.

“And think of that touching scene at end of ‘Walküre.’ Brünnhilde has to be punished, but Wotan doesn’t want to do it because he loves her. So he puts the fire all around her as a kind of compromise. The confrontation between Wotan and Fricke in Act 2 of ‘Walkure’ is one of the best domestic quarrels in the history of theater.

“At its core, the ‘Ring’ spins a long thread that develops from ‘Rheingold.’ It is Wotan’s desire for grandeur for the gods and the role the gold plays in that. It’s all about corruption in the desire for riches, domination and power. And it’s more true in our society today than it ever was.”

If Wagner’s tetralogy occupies center ring in the immediate circus of Davis’ life, the concerts at hand with the Chicago Symphony are not his only diversion in view. At Lyric, he will conduct a spring production of Tchaikovsky’s operatic psycho-drama “The Queen of Spades.”

“Oh, right, that other little thing I have to do before the ‘Ring,’” said the dauntless conductor with a laugh, and a sigh. “I probably should have picked something shorter.”

Related Links:

- Andrew Davis conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, ticket and performance info:Details at CSO.org

- Wagner’s ‘Ring’ cycle at Lyric Opera of Chicago, ticket and performance info:Details at LyricOpera.org