Chicago Symphony throw-down is private: musicians and trustees only; all others beat it

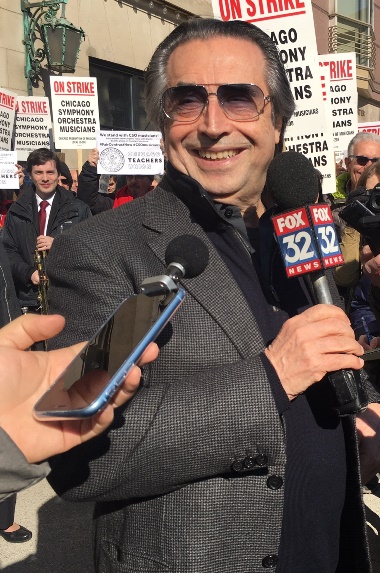

Musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra have been picketing in front of Orchestra Hall since the strike began March 11. (Nancy Malitz photo)

Commentary: CSO strike is not for outsiders to referee, and it’s not about the music-loving public. A settlement will define what is fair.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

The strike by musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, now entering its second month, has brought into focus some realities about high-level orchestras in our time, the nature of work stoppages such as this one and the framework of negotiations between musicians and management.

Perhaps the first point to be made is the inappropriateness of outsiders to presume to judge how an impasse in negotiations should be resolved. It’s probably safe to say that reporters don’t know enough to declare one side or the other culpable, intransigent, naive or unrealistic.

When Riccardo Muti arrived to conduct CSO concerts in March, only to find his musicians on strike, he gave outspoken support to their cause. (Nancy Malitz photo)

It is for the negotiating parties to determine what is agreeable, and what is agreeable to both parties must be recognized by all outside interests as fair.

This leads one to the related matter of the importuned public. Negotiations to resolve a musicians strike have nothing to do with the disappointment of the concert-going public or its impatience to hear the band play Beethoven again. A pitched-battle strike such as the one at hand is not about season ticket holders; it’s solely and entirely about the demands of the aggrieved musicians versus the willingness of management to meet those demands fully or partially – to whatever degree may be required to achieve an agreement.

The Chicago Symphony musicians have but one obligation to their public: to give their very best at every performance. Neither the musicians’ union nor the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association has any moral bond to consider the public as a factor in its negotiations. Contract negotiations are an exclusive throw-down between those parties. The rest of us are mere spectators – perhaps opinionated and probably ill informed, but spectators withal.

If that is true, one might ask, if an orchestra isn’t there basically for the pleasure of the public, what can be its raison d’être at all? This excellent question is the very drill to take us down to an old, hard truth. And getting at the answer requires changing that prepositional phrase for the pleasure to at the pleasure.

From its beginnings in the mid-18th century, the symphony orchestra as we have come to know it today has existed at the pleasure of the very wealthy, first as court ensembles such as the one over which Haydn presided at Esterházy and then in the 19th century as public institutions. It’s not all that old a concept, this imposing cadre of highly accomplished musicians playing music writ large. But it has always been very expensive at anything like the level of the Chicago Symphony.

The CSO in performance, with music director Riccardo Muti on the podium, was a familiar scene at Orchestra Hall before the current strike began March 11. (Todd Rosenberg photo)

Ticket sales have never paid the freight. Admissions cover 40-45 percent of the operating costs; the substantial balance comes from contributions, and that’s where a board of trustees comes in. Trustees: those to whom the fiscal well-being of an orchestra is entrusted. The ranks of orchestra trustees are always dominated by the very wealthy, who from their own resources and the help of their wealthy associates provide the lifeline that keeps an orchestra afloat.

But back to that defining phrase at the pleasure. Not only does an orchestra subsist at the pleasure of the wealthy, but that same slim sector of the community also determines the quality of the ensemble – by guaranteeing the resources needed to support salaries and benefits, including pensions, the sticking point of the current impasse. Here is where the separateness of wealth and artistry grows stark.

I have been covering symphony orchestras, including assorted strikes, in various cities for 50 years. And I have become familiar with a kind of motivational mantra among orchestra trustees who may have very little personal interest in music but believe wholly in the value of a good orchestra to their community. The short version is that it’s good business: The presence of a fine orchestra helps to draw the best and brightest to work in your city.

The Chicago Symphony happens to be rather more than a strong lure. It is probably the best orchestra in the country; indeed, in the same breath with Chicago, only two other orchestras in the world are typically invoked: the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic.

Muti led the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in a performance of Rossini’s Stabat mater to cap the 2017-18 season. (Todd Rosenberg photo)

But what does that mean, the best? How are such bragging rights achieved? In part, the answer bespeaks the consensus judgment of critics around the world, and it’s reflected in the hordes of musicians who come to Chicago to audition for any opening in this orchestra. The problem is, sustaining pinnacle greatness comes at a commensurate price.

The breath-taking performances the Chicago Symphony delivers on a weekly basis represent an assemblage of a hundred or so of the best musicians in the world. Such rarefied music-making doesn’t just happen and it isn’t self-sustaining. This, of course, is where music director Riccardo Muti comes into the picture. One could argue, and forcibly, that the Italian maestro is not just the greatest conductor but also the most brilliant living musician in the classical tradition. He likes to speak of the Chicago Symphony as his Ferrari.

Or as the late conductor Lorin Maazel put it, after leading the CSO in a rehearsal of Brahms’ Second Symphony on an Asia tour: “My God, what a sound.”

The sound of an engine made of exquisite parts.

And so we come to the present state of loggerheads. What will be the pleasure of the CSO trustees: to ensure that the local orchestra – “The World’s Best, Chicago’s Own,” the banner reads – remains exemplar to the world, or to risk its decline into something a bit less: perhaps very good, terrific on a given night?

Whatever the outcome, it’s strictly the business of the musicians and the Chicago Symphony’s financial stewards. Long term, the trustees will get what they are willing to pay for. It was ever thus.