Manfred Honeck steps in with CSO, tweaks program, delivers exhilarating ‘Pathétique’

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Manfred Honeck; Robert Chen, violin. At Orchestra Hall.

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Manfred Honeck; Robert Chen, violin. At Orchestra Hall.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

On Feb. 27, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra will observe the 120th anniversary of its founding with a celebratory concert under its present music director, Manfred Honeck. As patrons of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra have just witnessed, Honeck surely will give Pittsburgh reason for celebrations to come.

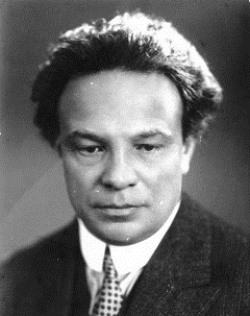

The 57-year-old, Austrian-born conductor stepped in for the CSO’s ailing and again absent music director Riccardo Muti to lead concerts Feb. 18-20, after the Russian maestro Gennady Rozhdestvensky had filled Muti’s vacancy the previous week.

The 57-year-old, Austrian-born conductor stepped in for the CSO’s ailing and again absent music director Riccardo Muti to lead concerts Feb. 18-20, after the Russian maestro Gennady Rozhdestvensky had filled Muti’s vacancy the previous week.

Although Honeck picked up part of Muti’s planned program – Respighi’s “The Fountains of Rome” and his “Concerto gregoriano” with CSO concertmaster Robert Chen as violin soloist – it was the elegance and power he brought to a replacement work, Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 in B minor (“Pathétique”) that displayed the conductor’s art at its most complete and impressive.

What is so marvelous about the “Pathétique,” what keeps it ever fresh and alluring like the symphonies of Brahms or Beethoven, is not at all what one listens for in German symphonies. Tchaikovsky was not concerned about classical form as the basis of dramatic structure; the case might be made that, as a musical architect, he was closer in spirit to Schubert or indeed Bruckner: a builder of lyrical edifices whose ineffable superstructure used the material of song, emotion, even psychology.

Such a glorious metaphysical arc was the airy frame of Honeck’s “Pathétique,” and he elicited from the CSO a performance of transcendent beauty and breathtaking precision. At the risk of zooming in on the obvious, the third movement’s march-scherzo, with its spectacular exchanges between strings and winds, was hair-raising: lustrous, precise string playing pitted against agile woodwinds and gleaming brasses.

I said obvious, but the striking quality of Honeck’s account was that he did not go for the obvious. He held back, progressively building the musical tension until it spilled over into unbounded exhilaration. I’m not sure how many orchestras in the world could deliver exactly what Honeck sought, but the CSO tossed it off with almost casual bravura.

It’s understandable that listeners would want – perhaps need – to burst into applause at the end of such a pyrotechnical display, but Honeck raised both arms to stop that and to signal the start of the tragic finale. Here, too, he brought his own dramatic perspective: poignancy rather than grief, a dark song as if in melancholy remembrance.

One might have taken issue with Honeck’s view of the symphony’s dreamy – I would have said almost languid – second movement, which at his headlong pace acquired a curious urgency. Still, the CSO gave back what was asked in brilliance and, fast though it was, the musical contours never lacked grace.

The work not played, from Muti’s original agenda in this CSO 125th anniversary season of exhuming premieres over the orchestra’s history, was Alfredo Casella’s Symphony No. 3, which was a Chicago Symphony commission in observance of its 50th year.

But Honeck honored the plan to showcase Chen in Respighi’s “Concerto gregoriano,” which the CSO gave its American premiere in 1924. The work had not been played by this orchestra in 50 years, since Victor Aitay, then co-concertmaster took the solo part under Jean Martinon. It isn’t hard to see how the concerto might been allowed to languish.

But Honeck honored the plan to showcase Chen in Respighi’s “Concerto gregoriano,” which the CSO gave its American premiere in 1924. The work had not been played by this orchestra in 50 years, since Victor Aitay, then co-concertmaster took the solo part under Jean Martinon. It isn’t hard to see how the concerto might been allowed to languish.

The designation “gregoriano” comes from Respighi’s allusions to medieval plainchant, with even one glancing paraphrase of the “Dies irae.” Actually, the work’s antique charm doesn’t seem all that distinctive; Vaughan Williams went for much the same modal exoticism in his “Tallis Fantasy,” and with more convincing results.

As an orchestrator, Respighi was exceptionally adept: Witness “The Fountains of Rome,” which Honeck and the CSO infused with blazing colors. And this violin concerto begins with great lyrical promise; but ultimately, it seems to run out of cogent ideas. While it was a pleasure to revel in Chen’s rich sound, much of that experience came wrapped in a sense of the composer’s self-conscious meandering in uninspired pursuit of ancient effects.

This has been a big problem with the CSO’s determined 125th-anniversary revival of works the orchestra premiered decades ago but which, by and large, have since fallen into neglect. Programming this season has too often suggested that the Chicago Symphony is facing the wrong direction: backward into dustbins rather than forward to new vitality, new horizons, new sounds.

Related Link:

- Preview of the Chicago Symphony’s complete 2015-16 season: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Tags: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Manfred Honeck, Ottorino Respighi, Pittsburgh Symphony, Robert Chen

No Comment »

1 Pingbacks »

[…] Last season, Honeck stepped in with CSO for exhilarating Tchaikovsky: Read the review at Chicago On the Aisle […]