Australian drama troupe transcends handicaps with serio-comedy full of backstage laughter

Review: “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich,” created and produced by Australia’s Back to Back Theatre, performed May 16-19 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago ★★★

Review: “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich,” created and produced by Australia’s Back to Back Theatre, performed May 16-19 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago ★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

If the title “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich” provokes more than the usual curiosity about fresh dramatic fare, the play itself — presented by the ensemble that created it, Australia’s Back to Back Theatre – leaves one hardly less perplexed upon emerging from the experience. “Ganesh” displays a singular aspect of beauty, even sweetness, until it takes a bitter turn and dissipates as if into a vacuum, into nothingness.

Back to Back Theatre, directed by Bruce Gladwin, is a company of actors with disabilities, either physical or intellectual. Under the artistic direction of Bruce Gladwin, the seven-member troupe, established in 1988, devises and acts in original plays, of which “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich” is the latest. In a brief Chicago stop this weekend, this impressively skillful, disciplined and certainly bold troupe brought “Ganesh” to the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Back to Back Theatre, directed by Bruce Gladwin, is a company of actors with disabilities, either physical or intellectual. Under the artistic direction of Bruce Gladwin, the seven-member troupe, established in 1988, devises and acts in original plays, of which “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich” is the latest. In a brief Chicago stop this weekend, this impressively skillful, disciplined and certainly bold troupe brought “Ganesh” to the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Structurally, “Ganesh” applies the classic device of a play within a play: A company of handicapped actors (who use their real first names) is in early rehearsal of a play written by one of their number. Set in 1943, it is about a quest by the Hindu god Ganesh to retrieve the swastika, a time-honored symbol of good luck, from the Nazis. As we watch episodes of the interior play take shape, we also eavesdrop on backstage business – the director’s notes to his actors, the personal digressions, the sympathetic hand-holding when egos get bruised, the interpretive discussions that sometimes flare into rancorous arguments.

And all the while, we’re inescapably fascinated by the fact that we’re watching actors who have managed their focused and convincing performances despite their various – and variously severe – physical or intellectual handicaps. Only the director is not affected by some handicap.

And all the while, we’re inescapably fascinated by the fact that we’re watching actors who have managed their focused and convincing performances despite their various – and variously severe – physical or intellectual handicaps. Only the director is not affected by some handicap.

Make no mistake, these are skilled actors seriously invested in their roles, their theatrical virtuosity extending to the pinpoint-precise art of comedy. They even make their handicaps the object of jokes. But what’s really funny are the temperamental flare-ups “backstage” requiring the director’s soothing intervention and reassurance. In that respect, this troupe is no different from any other acting company.

The interior play, concerning Ganesh’s quest to recover the swastika, is deadly serious. On his journey to Nazi Germany, the elephant-headed Ganesh – abetted by the higher deity Vishnu – sometimes must make difficult moral choices between serving the interests of the few and the good of the many, for the survival of the entire universe is at stake here. We see Ganesh’s problem personalized in a Jew who is subjected to close interrogation and threats by a Nazi official: Can the deity pause to shelter this one man or must he hasten on and leave the poor soul to his fate?

But the play within almost doesn’t come off. After the director has patiently prodded and consoled his actors, and inspired them to see the bigger picture when individual scenes befuddle them, a major blow-up comes. It’s as sudden and alarming as it is unforeseeable. Yet a show must always go on, and the players indeed regroup to complete their production.

But the play within almost doesn’t come off. After the director has patiently prodded and consoled his actors, and inspired them to see the bigger picture when individual scenes befuddle them, a major blow-up comes. It’s as sudden and alarming as it is unforeseeable. Yet a show must always go on, and the players indeed regroup to complete their production.

Whether as much can be said for the outer play is debatable. The interior crisis also affects the larger play – the shell structure. We seem to see that shell collapse into what might be characterized, with some indulgence, as theater of the absurd. It’s as if the vinyl partitions so effectively used to define spaces in the play have all dropped away, revealing not just empty space, but a dramatic void.

This wrenching turn brought to mind a similar play within a play offered last season at Victory Gardens — Jackie Sibblies Drury’s prodigiously titled “We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South-West Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915.” But whereas the thunderbolt near the end of Drury’s play struck like a blow to the solar plexus, the comparable moment here simply left one to wonder where the play had gone.

One might raise another caveat, or actually an objection: Midway through the proceedings, the director, illustrating for a troubled actor the difference between what’s real and what’s not, turns to face the audience and deliver a condemnation of our having shown up to watch “a freak show.” Then he turns back to the actor and says, in effect, “You see, I’m speaking to empty seats right now. This isn’t real.” I wonder how many in the audience squirmed a bit, sensing that the preceding harangue, its rhetorical frame notwithstanding, was quite real, a palpable instance of épater la bourgeoisie and one that crowded the margin of contempt.

I can speak only for myself. I was there to see a good play, which, up to a point, I did.

Related Link:

- Events coming up at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago: Details at MCAChicago.org

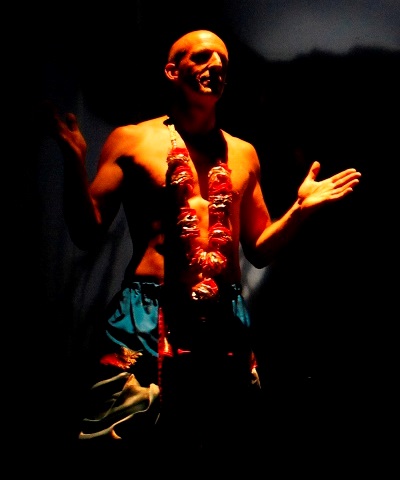

Photo captions and credits: Home page and top: The sly interrogation of a Jew (Simon Laherty, left) by a Nazi official (David Woods) aboard a train is translated from German to English in projected surtitles. Descending: Brian Tilley as the elephant-headed deity Ganesh confronts a Nazi official (David Woods). The supreme Lord Vishnu (David Woods) guides Ganesh on his journey. Simon Laherty as Adolph Hitler. (Photos by Jeff Busby)

Tags: Back to Back Theatre, Bruce Gladwin, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago