‘Pass Over’ at Steppenwolf: Two black guys hanging out on a corner, waiting for to go

Review: “Pass Over” by Antoinette Nwandu, world premiere at Steppenwolf Theatre through July 9. ★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

We are political creatures. We all have our world-view, our personal dispositions, our social sympathies and antipathies. That applies as well to creations for the stage. It is an ineluctable truth that all theater is political, even if some plays are more specifically agenda-driven than others.

That said, I have short patience with the more overt, I might say hell-bent, forms of agenda theater. They tend not to be very good drama. Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen’s “The Exonerated” springs to mind. Antoinette Nwandu’s play “Pass Over,” in its world premiere run at Steppenwolf, is no simple rant but does come with its own set of problems.

I was not put off so much by the political slant – two young black men paralyzed by what they see as a hostile, indeed closed, white society, its borders protected by a police force armed and eager for any excuse to shoot to kill. That’s a point of view expressed within the context of the play; it isn’t even necessarily the playwright’s position. It isn’t Shakespeare who utters this cynical observation on man: “What is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me: no, nor woman neither…,” but rather it is his tormented character Hamlet.

I was not put off so much by the political slant – two young black men paralyzed by what they see as a hostile, indeed closed, white society, its borders protected by a police force armed and eager for any excuse to shoot to kill. That’s a point of view expressed within the context of the play; it isn’t even necessarily the playwright’s position. It isn’t Shakespeare who utters this cynical observation on man: “What is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me: no, nor woman neither…,” but rather it is his tormented character Hamlet.

What troubled me about “Pass Over,” an ambitious and passionately executed project by a clearly talented writer, was not its politics, but a dramatic fabric stretched thin. Nwandu, in her mid-thirties, possesses a distinctive voice and a ready flair for the emotional rhythm as well as rhetorical pulse of the language of her subjects.

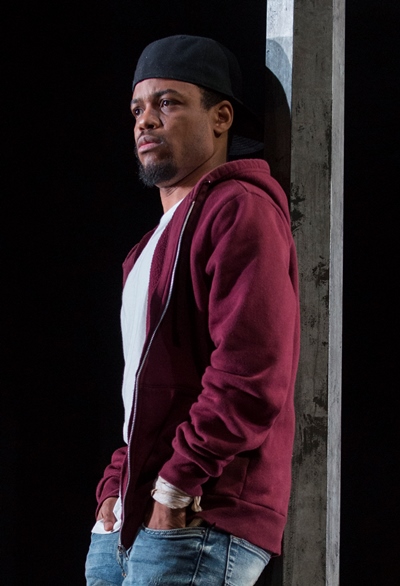

The two kids – maybe they’re even twentysomething, but they have a lot of kid in them – at the center of Nwandu’s play are charming jokesters who want desperately to transcend, break out. They’re just, as it were, waiting to do so. Nwandu acknowledges, in an interview in the program booklet, that her conceptual model was Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot.” Instead of waiting for somebody to show up, these lads – the forthright Moses (Jon Michael Hill) and the follower Kitch (Julian Parker) – are hanging out on a corner waiting to cross over, into the land of milk and honey, the land of opportunity, the domain of white people.

Their speech is salted with profanity, mostly in a good-humored spirit. They use the N-word like breathing out and breathing in. It’s their patois. Here is my problem with it: In that same printed interview, Nwandu says she personally came to hear an ineffable (my word) lyricism in the language of black streets. I couldn’t agree more about the lyrical potential. I twice saw Stephen Adly Guirgis’ play “The ______ With the Hat,” first on Broadway and later at Steppenwolf, in which the torrent of profanity is deeply and variously expressive, indeed lyrical. But Nwandu doesn’t quite attain that poetry, anyway doesn’t sustain it.

Their speech is salted with profanity, mostly in a good-humored spirit. They use the N-word like breathing out and breathing in. It’s their patois. Here is my problem with it: In that same printed interview, Nwandu says she personally came to hear an ineffable (my word) lyricism in the language of black streets. I couldn’t agree more about the lyrical potential. I twice saw Stephen Adly Guirgis’ play “The ______ With the Hat,” first on Broadway and later at Steppenwolf, in which the torrent of profanity is deeply and variously expressive, indeed lyrical. But Nwandu doesn’t quite attain that poetry, anyway doesn’t sustain it.

In language and action alike, “Pass Over” grows repetitive. The play needs tightening. Credit Hill and Parker – and director Danya Taymor — with stretching interest in their characters to the max. But this drama runs short on substance well before its rather ham-handed denouement.

Which brings me to the third character, or rather the two surreal characters played by Ryan Hallahan. As Mister, a dopey, smarmy white guy in an ice cream suit, he comes upon the dithering black kids bearing a picnic basket brimming with goodies, on the pretext that he was looking for his mother’s house and got lost. He’s the polar opposite of these street-wise youths, a regular golly-gee-whiz kind of guy ready to share his bounty with his hungry-looking new friends. Aside from one tiny little vicious outburst, which he instantly swallows, Mister is a picture of white kindness.

Which brings me to the third character, or rather the two surreal characters played by Ryan Hallahan. As Mister, a dopey, smarmy white guy in an ice cream suit, he comes upon the dithering black kids bearing a picnic basket brimming with goodies, on the pretext that he was looking for his mother’s house and got lost. He’s the polar opposite of these street-wise youths, a regular golly-gee-whiz kind of guy ready to share his bounty with his hungry-looking new friends. Aside from one tiny little vicious outburst, which he instantly swallows, Mister is a picture of white kindness.

Mister withdraws and in his place appears a cop. He has a name, but it comes up only in the cast list: Ossifer, which I construe as a conflation of Officer and Lucifer. To Moses and Kitch, that would be one and the same anyway. There is no kindness in the cop, only taunts and degradation and thinly veiled threats.

But by the time the cop comes around again, Moses has resolved once and for all to lead his people (Kitch) out of bondage – to get off that corner, to cross over. I suppose the play might have been titled “Crossing Over,” but Nwandu has a purpose in her actual title. Confronted again by the demonic cop, Moses gets in his face, even inviting the officer to shoot him now: Why not, the youth says, it’s going to happen eventually. (Hamlet again: “If it be now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all.”)

And just as the cop is ready to oblige him, well, events take a strange turn. One infers divine grace. Followed shortly by another 180-degree turn that I shall leave to discovery by the curious – except to note that the final flourish rather crisply restores social order as it has long been understood on this particular corner.

Message transmitted. At least one viewer wanders off unconvinced by the drama.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: Antoinette Nwandu, Danya Taymor, Jon Michael Hill, Julian Parker, Ryan Hallahan, Steppenwolf Theatre