Muti, leading the CSO through Brahms cycle, says unsuspected sadness edges symphonies

Interview: Even after decades of experience with Brahms, Riccardo Muti is still making discoveries about the great composer’s music.

By Nancy Malitz

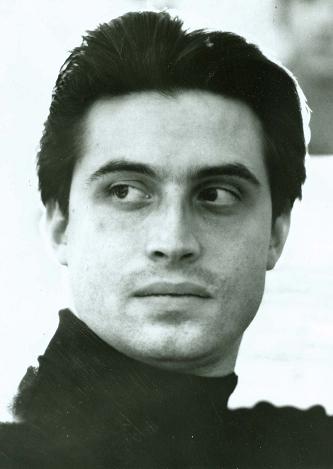

Riccardo Muti has been conducting the symphonies of Brahms for 45 years, but to his current total immersion project with the Chicago Symphony – two weeks of all-Brahms – he brings the excitement of a perpetual student.

In a conversation with Chicago On the Aisle after performing the First and Second Symphonies, with the Third and Fourth scheduled through May 13, Muti said he was thrilled with the way things were going and relayed the exhilaration of discoveries that have put into focus his remarkable experiences with Brahms as a young man.

In a conversation with Chicago On the Aisle after performing the First and Second Symphonies, with the Third and Fourth scheduled through May 13, Muti said he was thrilled with the way things were going and relayed the exhilaration of discoveries that have put into focus his remarkable experiences with Brahms as a young man.

The 75-year-old maestro’s first big orchestra job was in Florence, Italy, as principal conductor and music director of the famed Maggio Musicale after winning first place in the Guido Cantelli Competition for Conductors in Milan in 1967 to unanimous acclaim. He was only 27 years old, enormously talented but still green when he assumed the directorship.

“I had to learn the basic repertoire, little by little,” Muti recalled. “I think I did the First, Second and Fourth Symphonies of Brahms there, but these were the typical performances of a young man who approaches the big repertoire. The first real understanding of Brahms came for me in 1975, when I did the Second Symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic.”

Those circumstances were equally extraordinary: Then 34, Muti made his Vienna Philharmonic subscription debut and picked up the latter part of the Philharmonic’s tour of Japan. The tour was headlined by the greatly esteemed Austrian conductor Karl Böhm, an octogenarian who was somewhat frail and 47 years Muti’s senior. The young maestro joined the traveling forces in Tokyo, plunging in with Brahms Second:

Those circumstances were equally extraordinary: Then 34, Muti made his Vienna Philharmonic subscription debut and picked up the latter part of the Philharmonic’s tour of Japan. The tour was headlined by the greatly esteemed Austrian conductor Karl Böhm, an octogenarian who was somewhat frail and 47 years Muti’s senior. The young maestro joined the traveling forces in Tokyo, plunging in with Brahms Second:

“I immediately started to glimpse at least the melancholy in the work. Of course, I was quite nervous to conduct this Brahms with the orchestra that had performed practically under him.” (Brahms was an eminence in Vienna; he conducted the orchestra in a number of his own works during his time as director of concerts at the Musikverein, and Brahms’ Second and Third Symphonies were premiered by the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter.)

“So as I conducted the Viennese in the Second Symphony, I realized at a certain point that they were telling me how. It’s not that I was following the orchestra, because I’m a little authoritarian,” he added with a slight grin.

“I would never follow. But I was clever enough to realize that it was important to listen, because the orchestra has a certain way. You can attempt to imitate it, but when you do so, you exaggerate, and it becomes sort of a mannerism. I started to get a sense of what they were doing – the phrasing, and a dynamic sense that is disappearing today, because orchestras now only play from mezzo-forte to fortissississimo (medium loud to extremely loud). And also, this remarkable melancholic sound is something the Viennese musicians have by nature.”

“I would never follow. But I was clever enough to realize that it was important to listen, because the orchestra has a certain way. You can attempt to imitate it, but when you do so, you exaggerate, and it becomes sort of a mannerism. I started to get a sense of what they were doing – the phrasing, and a dynamic sense that is disappearing today, because orchestras now only play from mezzo-forte to fortissississimo (medium loud to extremely loud). And also, this remarkable melancholic sound is something the Viennese musicians have by nature.”

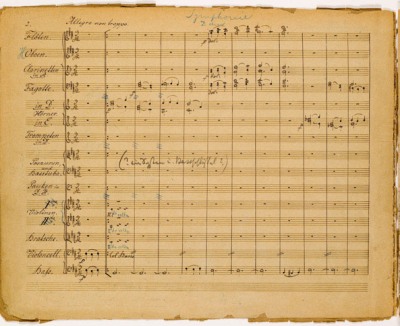

It took many more years, Muti said, before he fully understood the melancholy as it pertains to Brahms even in his Second Symphony, which is in D major and often described as sunny. Muti consulted with Otto Biba, the director of the library archive at the Musikverein, who shared some pages that Muti brought in turn along to Chicago – a letter from Clara Schumann to the conductor Hermann Levi, reporting that Brahms had finished, in his head, a Symphony in D major of a quite elegiac character.

And that same year, in a letter to his publisher Simrock, Brahms declared that his new symphony, the Second, was “so melancholic you won’t stand it. I have never written anything so sad, so soft, the score must appear with a black border.” And in 1879, a letter from Brahms’ colleague Vincenz Lachner asked why Brahms had used the gloomy, lugubrious tones of trombones and tuba and kettledrum in the Second Symphony, gravely affecting the euphony. In reply, Brahms confessed that “I am, by the by, a severely melancholic person,” and that “black wings are constantly flapping above us.”

“When the librarian gave me this,” Muti said, “I thought, ‘So. I have been wrong all this time.’ I finally understood the kind of melancholic sound that the Viennese made the first time I worked with them. In the years since then, I enlarged my repertoire and began doing a lot of Bruckner and Mahler and Schoenberg, and also Schubert — music before and after Brahms – and it has given me the possibility of looking at Brahms’ symphonies in a completely different way.

“When the librarian gave me this,” Muti said, “I thought, ‘So. I have been wrong all this time.’ I finally understood the kind of melancholic sound that the Viennese made the first time I worked with them. In the years since then, I enlarged my repertoire and began doing a lot of Bruckner and Mahler and Schoenberg, and also Schubert — music before and after Brahms – and it has given me the possibility of looking at Brahms’ symphonies in a completely different way.

“Before, what I did was not superficial, but I think I was less ready to do this composer. Even today, Brahms is approached by conductors in many different ways. Some give him a German heavy weight, too heavy. Some are perhaps too lyrical. I think we should not forget the ‘black wings that are constantly flapping’ even when the music seems serene, tranquil. He was a complex personality, never married, this haunt always on him.”

At hand through May 13 are the Third and Fourth Symphonies, which Muti says are not really a pair, but totally different from each other: “The Third for me is musically the most interesting, the most melancholic and melodically very beautiful, but it is the less performed because it ends softly and generally the public reacts more strongly to loudness in the final flourish.” Muti added that when Liszt wrote his “Dante” Symphony, which ends softly, he also provided a louder second finale which the conductor could append ad libitum. “So Liszt understood this problem,” Muti said. “He was a man of the world.”

At hand through May 13 are the Third and Fourth Symphonies, which Muti says are not really a pair, but totally different from each other: “The Third for me is musically the most interesting, the most melancholic and melodically very beautiful, but it is the less performed because it ends softly and generally the public reacts more strongly to loudness in the final flourish.” Muti added that when Liszt wrote his “Dante” Symphony, which ends softly, he also provided a louder second finale which the conductor could append ad libitum. “So Liszt understood this problem,” Muti said. “He was a man of the world.”

Muti’s Brahms solution is to program the Third Symphony on the first half of the concert, leaving the Fourth Symphony, with its brilliant, intellectually complex passacaglia finale, to end it. “But the more you perform the symphonies together, you realize the melancholic streak is always there, in each of them,” he said.

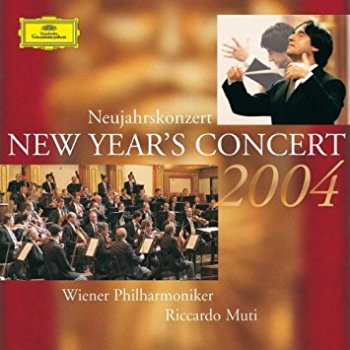

Muti will be conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in its internationally televised New Year’s Day concert for the fifth time in his career, capping his 47th consecutive season as a performer with that venerable ensemble and its strong link to the Brahms tradition. “What is important for me is that I started by working with orchestra musicians who had played under Wilhelm Furtwängler, Bruno Walter, Clemens Krauss, Josef Krips and Arturo Toscanini – I am talking about the older generation of musicians who knew those conductors, and who were still playing in the orchestra,” Muti said.

Muti will be conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in its internationally televised New Year’s Day concert for the fifth time in his career, capping his 47th consecutive season as a performer with that venerable ensemble and its strong link to the Brahms tradition. “What is important for me is that I started by working with orchestra musicians who had played under Wilhelm Furtwängler, Bruno Walter, Clemens Krauss, Josef Krips and Arturo Toscanini – I am talking about the older generation of musicians who knew those conductors, and who were still playing in the orchestra,” Muti said.

“From them I learned a lot. And now, when I go back to Vienna as an old conductor, they wait eagerly for me because I am one of the very few conductors left that can bring back that sound they are trying not to lose. Today, with younger conductors, there is a sound typical of the CD, a more machine-like sound rather than something that is an expression of the culture of a certain country. Thirty or forty years ago, you could identify through the radio whether you were hearing the Berlin Philharmonic or a French, American or Italian orchestra — some sounded thick, some like velvet, the Italians a little more lyrical.

“And you could always recognize the Vienna Philharmonic. For Brahms, Vienna is perfect. People think that Brahms was German – OK, he was born in Hamburg, but Brahms’ soul, his heart, is Vienna. And Brahms’ sound comes out of Schubert, who wrote Lieder, and who liked the voice, and whose music is always singing. I have now seen three generations of musicians in the orchestra: At the beginning the old players were going to pension. That was in ’71. Then a new generation came in, and now a third generation is already starting to have white hair. And so that’s almost a half century of working continuously with them, and they said all the time, ‘Maestro, remember, Brahms comes from Schubert.'”

Even though Muti finds the American way of doing Brahms typically bigger and more Germanic, he says the Chicago Symphony musicians have readily assimilated the more Viennese approach. “When Brahms asks for a pianissimo, if you play a real pianissimo as the Chicago Symphony does, the transparency of the score comes out,” he said, adding that after seven years working shoulder to shoulder, the orchestra responds “without having to make that extra effort to try to understand. Doing all the Brahms together like this has been a revelation for us all.”

Related Links:

- Review of the first concert in the Brahms project: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

- Second Brahms program location, dates and times: Details at CSO.org

- Muti returns for a program of Italian opera excerpts in June: Details at CSO.org

- Muti on Schubert: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

- Muti on Bruckner: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

- Riccardo Muti’s website: Go to RiccardoMuti.com