‘Death of a Salesman’ at Redtwist: Bringing resonant life to a fractured soul on the brink

Review: “Death of a Salesman” by Arthur Miller, at Redtwist Theatre, extended through March 26. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Brian Parry’s heartbreaking performance as Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” at Redtwist Theatre is the finest work I’ve seen on a Chicago stage this season. A virtually tactile experience in a tiny, in-your-face venue, this is gigantic acting on the most intimate scale.

Even better for theater buffs, the show’s run has been extended through March 26. Redtwist’s “Death of a Salesman” should go straight to the top of any must-see list, and not only for Parry’s indelible portrait of a good man who drowns in the churn of his illusions and lost dreams.

Directed by Steve Scott with an unfailing ear for language, dramatic contour and interplay, the production boasts a smart and credible supporting cast of vivid characters. But as in Miller’s “A View from the Bridge,” however brilliant the encircling group, it is the desperate figure at the center to which the eye constantly returns and upon which the whole crushing tragedy hangs.

Miller introduces us to Willy in mid-spiral. He’s 60 years old, a traveling salesman who once blazed trails for his old boss, opened up new territories, did great things. That’s all in the past. The old magic just doesn’t work any more. Willy has trouble bringing home enough money to meet payments on the appliances and still make the mortgage on a house that’s almost paid off.

His wife Linda (Jan Ellen Graves in a quietly sympathetic turn) props up his splintering ego. But his grown sons, Hap and Biff – well, mostly they remind him of his failure as a father, as a husband, as a man. Somewhere in his pursuit of the American dream, Willy got sidetracked and became the poster boy for life as a lie.

Parry’s realization of Willy is profoundly human and deeply sad. The man wants so much to be worth something, but believes in his heart that he has lost all value – indeed comes to the conclusion that he might be worth more dead than alive. In his distraction, and in guilt over transgressions long past but irredeemable, he harangues at persons only he can see. He pleads to the past, admonishes ghosts, relives the small victories that once buoyed his heart.

It is a singular thing to be so close to a skilled actor that you can gaze through his eyes into the soul of his character, see the white in the knuckles that clench his weathered hat, catch the small falter in his step – hear the muted whimper in a voice that has lost its clarion ring. These are the withering particulars of Parry’s Willy, the almost unbearable subtleties of an actor who can stand 18 inches from you and render wholly credible the consuming misery of a fellow creature.

“Death of a Salesman” plays out largely through set pieces, tightly spun scenes that either recall Willy’s missteps or frame his present despair. These episodes meld one into another to move the play forward, a device that director Scott manages with equal parts of elegance and fluency. And each turning page raises the dramatic tension thanks to coherent, carefully calibrated portrayals around Willy.

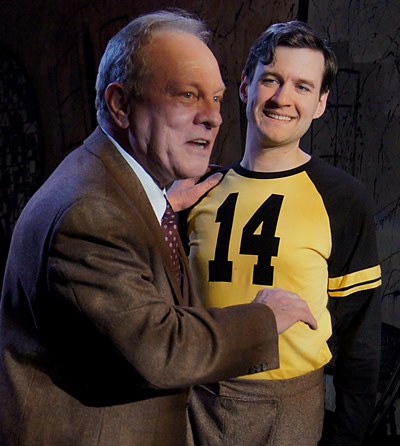

Elder son Biff (Matt Edmonds), an erstwhile high school football star once headed for great things, has distanced himself from the family, a rolling stone with neither plan nor ambition. Edmonds cuts an edgy angry young man who knows something about his father that has permanently stained their relationship.

Kid brother Hap (played with a poignant brand of exuberance by Benjamin Kirberger) has grown up in Biff’s shadow, the other son, still scarcely mentioned by his mother, unnoticed by his father. Small wonder Hap prides himself on his endless conquests of women.

Kid brother Hap (played with a poignant brand of exuberance by Benjamin Kirberger) has grown up in Biff’s shadow, the other son, still scarcely mentioned by his mother, unnoticed by his father. Small wonder Hap prides himself on his endless conquests of women.

The Loman household is a dysfunctional marvel, and its convulsions are underscored by the hard work, competence and success of the father and son next door – Willy’s pal Charley (Adam Bitterman), a flourishing businessman, and his brilliant son Bernard (Devon J. Nimerfroh), who tries in vain to tutor the football hero Biff.

Two of the play’s most resonant scenes, peak moments of this production, bring Willy face to face with Charley and the grown Bernard in quite different circumstances. Willy has never had a problem tapping Charley for fifty bucks to see him through, but in this illuminating scene, which Bitterman plays with no-nonsense directness and palpable compassion, Charley offers road-weary Willy a job – which he flatly rejects. The exchange between Bitterman and Parry is a piece of work, the former urging his friend to accept this genuine offer and the latter turning him down in absolute terms but with no explanation. It is one form of the pride that goeth before a fall.

In the second instance, Bernard, now graduated from college and about to try a case before the Supreme Court, asks Willy why Biff did not take the summer make-up course in math that would have enabled him to graduate and accept an athletic scholarship to a big-time college. Willy knows why. It’s part of an awful secret. But of course, he bobs and weaves and dissembles his way out the door. In Parry’s pathetic dance, you could feel the pain pushed to the surface by long years of self-loathing.

In the second instance, Bernard, now graduated from college and about to try a case before the Supreme Court, asks Willy why Biff did not take the summer make-up course in math that would have enabled him to graduate and accept an athletic scholarship to a big-time college. Willy knows why. It’s part of an awful secret. But of course, he bobs and weaves and dissembles his way out the door. In Parry’s pathetic dance, you could feel the pain pushed to the surface by long years of self-loathing.

And somewhere atop the hierarchy of Parry’s flights of sorrow came this: Punching himself up, Willy goes to see his current boss, son of the old one, to insist that all his years on the road should now be rewarded with a local assignment, for which Willy even suggests a salary. But the younger man (Michael Sherwin) only wants to show off his new tape-recording machine and the preserved babbling of his precious child and flummoxed wife. In desperation, Willy drops his price, then again, to no avail. It does not end well.

Willy sees the writing on the wall – and in it a clear plan. Parry’s radiant vision of the good this fractured man still might do is a consummation deeply to be savored.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Brian Parry says he summoned courage before wit as George in ‘Virginia Woolf’: Read the interview at Chicago On the Aisle

- Preview of Redtwist Theatre’s complete 2016-17 season: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

Tags: Adam Bitterman, Arthur Miller, Benjamin Kirberger, Brian Parry, Death of a Salesman, Devon J. Nimerfroh, Jan Ellen Graves, Matt Edmonds, Michael Sherwin, Redtwist Theatre, Steve Scott

No Comment »

1 Pingbacks »

[…] M. Nixon in Peter Morgan’s “Frost/Nixon,” Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” and George in Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia […]