Apollo’s Fire, in belated Chicago debut, brings heat, refined style to evening of Baroque fare

Review: Apollo’s Fire concert Oct. 14 at the University of Chicago.

Review: Apollo’s Fire concert Oct. 14 at the University of Chicago.

By Kyle MacMillan

Even though Apollo’s Fire is based just across the Great Lakes in Cleveland and has attained international attention during its nearly 25-year-history, it had never performed in Chicago. That odd omission came to an end Oct. 14 in the University of Chicago’s Mandel Hall when the 16-member period-instrument ensemble opened the UChicago Presents’s 2016-17 season with plenty of sparks if not a full-fledged blaze.

Although it might not possess the improvisatory fervor of some of its peers, this group of first-rate musicians combines an air of refinement with an invigorating sprightliness and focus and an appropriately light, well-balanced sound.

Although it might not possess the improvisatory fervor of some of its peers, this group of first-rate musicians combines an air of refinement with an invigorating sprightliness and focus and an appropriately light, well-balanced sound.

The musicians perform standing up, and they brought obvious physicality to their playing, especially concertmaster Olivier Brault, who plays with a dancerly flair.

Founded in 1992 by harpsichordist and conductor Jeannette Sorrell, Apollo’s Fire has gained a reputation for imaginative programming that was borne out by the music on display here.

Sorrell understands that early music can be somewhat alien and challenging for new and sometimes even seasoned classical audiences, so it’s helpful to have a hook – a bit of context that allows listeners to get their bearings. Thus, rather than just a conventional assemblage of works, Sorrell devised a concert line-up that was intriguingly titled “A Night at Bach’s Coffeehouse.” (Her program notes, written in an engaging, conversational style, greatly aided in animating this idea.)

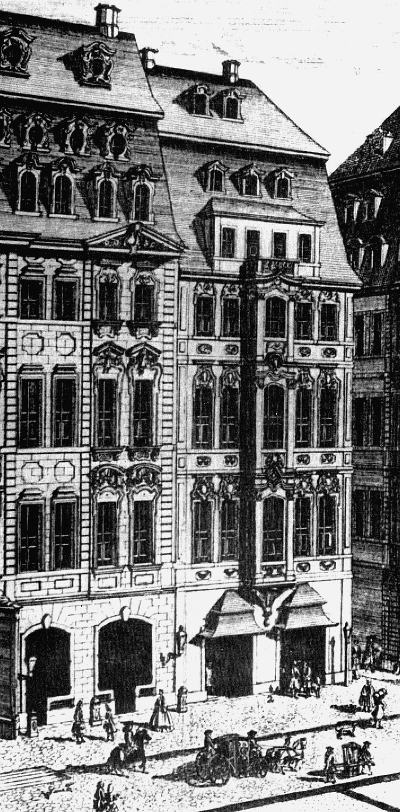

In addition to all his other musical duties, the seemingly indefatigable Johann Sebastian Bach oversaw informal weekly concerts at Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse, a popular gathering spot in 18th-century Leipzig. It allowed Bach to blow off steam and create and play music outside the sacred realm.

Based on her research of Bach’s activities at Zimmermann’s, Sorrell put together a group of works that might have been performed there, starting with six selections from Georg Philipp Telemann’s “Don Quixote” Suite, which was, of course, inspired by Cervantes’ famed 1605 novel. Bach was not only an admirer of Telemann, but it so happens that the latter composer also founded the Collegium Musicum, the informal student group that Bach led at the coffeehouse.

Based on her research of Bach’s activities at Zimmermann’s, Sorrell put together a group of works that might have been performed there, starting with six selections from Georg Philipp Telemann’s “Don Quixote” Suite, which was, of course, inspired by Cervantes’ famed 1605 novel. Bach was not only an admirer of Telemann, but it so happens that the latter composer also founded the Collegium Musicum, the informal student group that Bach led at the coffeehouse.

The suite was an ideal concert opener, allowing the group to show off its fine technique as well as its evocative musical storytelling abilities. Highlights ranged from the dreamy second section, “Don Quixote awakens,” with the light, iterative baroque guitar of John Lenti, to the charging propulsion of the third section, “His attack on the windmills,” and the wispy fourth part with sustained lines that aptly embodied the title, “Sighs of love for the Princess Dulcinea.”

Two of the Baroque era’s best known and most beloved works came next – Bach’s “Brandenburg” Concertos No. 4 and 5, which are part of a set of six of written around 1720 for varied combinations of instruments. No. 4 in G major featured Brault with Francis Colpron and Kathie Stewart, well-matched members of the orchestra who double on flute and recorder. Showcased on recorders, Colpron and Stewart performed with technical ease and a pleasingly soft-edged tone. A highlight of the work was a cadenza in the third movement with the three soloists engaged in a delightful fugal romp.

“Brandenburg” No. 5 in D major featured Sorrell, Brault and Stewart, this time on the traverso, a wooden Baroque flute. The first movement ends with a celebrated harpsichord solo that builds to an almost manic ferocity, and Sorrell handled it all with unflappable, sure-fingered virtuosity. Another high point arrived in the slow movement, with an affecting dialogue between Stewart and Brault, whose elegant, sensitive tone could be heard to advantage here.

After the Chaconne from Handel’s “Terpsichore,” a prologue he wrote for his opera, “Il pastor fido,” the evening came to a thrilling conclusion with Vivaldi’s version of “La Folia (Madness).” (The widely known folk dance was an inspiration to several other Baroque composers as well.) Just as Bach transcribed seven of Vivaldi’s violin concertos for keyboard, Sorrell re-arranged the Italian composer’s original trio for two violins and cello as a kind of concerto grosso. Here the musicians set aside their scores and performed from memory, a change that produced an unfettered responsiveness in their playing.

Sorrell and the musicians brought punch and drive to this pulsing, percussive work that speeds to an explosive conclusion. It was the kind of all-out playing that had been missing earlier in the concert, and it drew cheers and the heartiest applause of the evening.

The ensemble offered what at first seemed like a startling encore, an Appalachian folk tune called “Glory in the Meeting House.” But it turns out that Apollo’s Fire has recorded an album of such music, “Come to the River.” Its period-instrument style matches well with this venerable American idiom, which has distinct musical roots in Europe. As with “La Folia,” the players reveled in it.

Related Link:

- Complete 2016-17 season for UChicago Presents: Get the details here

Tags: Apollo's Fire, Francis Colpron, Jeannette Sorrell, John Lenti, Kathie Stewart, Olivier Brault