To young lives at risk, Muti and 2 opera stars bring close encounter with voice in full glory

Report: Youths at Juvenile Justice facility are responsive audience for singers Joyce DiDonato and Eric Owens, with the Chicago Symphony music director Riccardo Muti as host (and pianist).

By Nancy Malitz

Photos by Todd Rosenberg

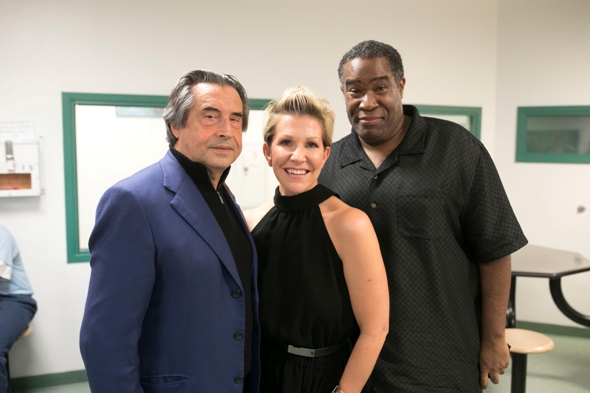

It was going to be a hectic week for classical music. Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato was about to make her Chicago Symphony Orchestra debut with music director Riccardo Muti in a rare Italian work, and bass-baritone Eric Owens, over at the Lyric Opera, was readying the role of Wotan, king of the gods in Wagner’s “Ring” cycle, for the first time in his career.

Yet these three internationally celebrated artists made time on Sept. 25 to perform for incarcerated youths within the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, where boys in conflict with the law, most of them in their mid to late teens, are held for an intensive period of education and intervention designed to set them on a safer course. Some were in the final stretch prior to release for offenses such as a parole violation, intent to distribute drugs and possessing or discharging a weapon.

Yet these three internationally celebrated artists made time on Sept. 25 to perform for incarcerated youths within the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, where boys in conflict with the law, most of them in their mid to late teens, are held for an intensive period of education and intervention designed to set them on a safer course. Some were in the final stretch prior to release for offenses such as a parole violation, intent to distribute drugs and possessing or discharging a weapon.

The inconspicuous entrance at the Illinois Youth Center-Chicago is tucked into a corner beneath a windowless warehouse façade at the back of a parking lot on the city’s west side. Once through heavy layers of security, the visiting musicians and a few observers entered into a capacious gym, where several solo players in the CSO were already warming up. A makeshift stage area had been set up at the sideline, between basketball hoops at either end.

Bells sounded and three groups of boys came in single file, organized by their housing units — younger teen wing, older teen wing, and members of the substance abuse program — about 70 blue T-shirts in all, settled into folding chairs, silent, their eyes checking out the silver tuba, the tiny piccolo, the drums, the guests. Assistant superintendent of programming Michael Byrd, in suit and tie, who knew his audience listened mostly to rap and hip-hop, announced that the boys were about to have an experience they’d probably never had before.

Bells sounded and three groups of boys came in single file, organized by their housing units — younger teen wing, older teen wing, and members of the substance abuse program — about 70 blue T-shirts in all, settled into folding chairs, silent, their eyes checking out the silver tuba, the tiny piccolo, the drums, the guests. Assistant superintendent of programming Michael Byrd, in suit and tie, who knew his audience listened mostly to rap and hip-hop, announced that the boys were about to have an experience they’d probably never had before.

Byrd had met Muti twice before at similar presentations and knew what was in store. “I love him,” Byrd said in a telephone interview. “At first I think I expected a world-renowned maestro to be a little lofty, but he is so down to earth. When he was here two years ago, he engaged the young men in conversation, and this time, when one of them was being a little too chatty, he went over and handled it like a pro, with a little joking, but setting a limit.”

Once the juveniles meet certain performance objectives, they can have transistor radios in their rooms, but Byrd said he doubted many had ever turned the dial to classical music: “Maybe it’s a socio-economic issue, but it’s also just a teen issue.” This is a rap and hip-hop world.

Muti’s a practiced hand at making contact through classical music, but so is Owens, who flew in to be part of a similar event with Muti in 2012, insisting, “This is most important work I can do.” For her part, DiDonato has been working on a project at Sing Sing, the maximum security facility in New York, where several musically gifted inmates wrote some music for her to sing. “Performing it was a deeply moving experience for me,” she said. “And now that they have an even better idea of what my voice can do, they’re writing me new songs. I’m definitely going back.”

Muti’s a practiced hand at making contact through classical music, but so is Owens, who flew in to be part of a similar event with Muti in 2012, insisting, “This is most important work I can do.” For her part, DiDonato has been working on a project at Sing Sing, the maximum security facility in New York, where several musically gifted inmates wrote some music for her to sing. “Performing it was a deeply moving experience for me,” she said. “And now that they have an even better idea of what my voice can do, they’re writing me new songs. I’m definitely going back.”

Among the juveniles in attendance on Sept. 25 were a 17-year-old and 18-year-old, both within weeks of completing their time at the Illinois Youth Center. They stated their chosen future career paths as architectural engineer and computer technician. (The center does not allow the youths to be indentified in photos or by name.) “That kind of singing was new to me,” said the first youth about DiDonato doing the aria “Lascia ch’io pianga” by Handel. The idea of an opera plot was of interest to him — “I had never heard of a story in music before” – and he said that when he got out he’d like to “go downtown to Muti and say thank you.”

DiDonato had explained she was singing the words of a female prisoner in chains, very sad, weeping at her cruel fate. The size and intensity of her voice startled quite a few youths in the room, and there were signs of their nervousness at first, but she got a huge ovation. The second youth, a big fan of pop and R&B, said that while there had been other assemblies in the months he had been there, including a visit by a church choir, the opera was “really beautiful and definitely something different.” At one time, he had played an acoustic guitar, he said, and would like to do so again.

DiDonato had explained she was singing the words of a female prisoner in chains, very sad, weeping at her cruel fate. The size and intensity of her voice startled quite a few youths in the room, and there were signs of their nervousness at first, but she got a huge ovation. The second youth, a big fan of pop and R&B, said that while there had been other assemblies in the months he had been there, including a visit by a church choir, the opera was “really beautiful and definitely something different.” At one time, he had played an acoustic guitar, he said, and would like to do so again.

Setting the crowd at ease with stories of his childhood, Muti told the crowd what even his avid classical music fans may not know – that he was a reluctant music student at first. “My parents decided they had better stop paying the teacher, because this idiot cannot even read the notes,” he said, pointing to himself. By the time Owens rounded off the afternoon with his introspective rendition of the spiritual “Deep River,” some common ground had been achieved.

Intervening cameos by a trio of CSO players offered a showcase of technical wizardry: When CSO principal percussionist Cynthia Yeh first learned Shane Shanahan’s drumming piece “Saidi Swing,” it was in a duet version, but this time she flew through it all by herself to whoops and hollers. And many in the hall – DiDonato and Owens included – shook their heads in wonder at the extreme high-low duet of CSO piccolo player Jennifer Gunn and CSO principal tuba Gene Pokorny in their deft take on Bach’s Double Violin Concerto.

Intervening cameos by a trio of CSO players offered a showcase of technical wizardry: When CSO principal percussionist Cynthia Yeh first learned Shane Shanahan’s drumming piece “Saidi Swing,” it was in a duet version, but this time she flew through it all by herself to whoops and hollers. And many in the hall – DiDonato and Owens included – shook their heads in wonder at the extreme high-low duet of CSO piccolo player Jennifer Gunn and CSO principal tuba Gene Pokorny in their deft take on Bach’s Double Violin Concerto.

Participation in the CSO’s outreach activities is voluntary, Pokorny said. As for how one measures the positive benefit of an activity such as this, the veteran musician frankly admitted he is unsure: “I would like to believe that perhaps a young person might at some time in the future remember that one day when an old guy came into the facility and played something unbelievable on a giant horn, and that it just remains an awesome memory that they think back to often, as something that was totally unexpected.

“I try to think not so much of the fact that this is first time they are hearing a tuba play a solo. I am thinking that this will be last time they will ever hear a tuba play a solo. This fact sets my bar higher to play really well.”

Related Links:

- The event was funded by the Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO: Read about Negaunee’s community engagement programming

- More on the CSO’s 2016-17 season: Read it at CSO.org

Tags: Cynthia Yeh, Eric Owens, Gene Pokorny, Illinois Youth Center-Chicago, Jennifer Gunn, Joyce DiDonato, Riccardo Muti