Bates’ new concerto is feather in violinist’s cap when Slatkin leads CSO in American concert

Preview: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin; Anne Akiko Meyers, violin. At Orchestra Hall through April 22.

Preview: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin; Anne Akiko Meyers, violin. At Orchestra Hall through April 22.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

What an engaging, stimulating change of pace, this weekend’s all-American concert fare offered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conductor Leonard Slatkin at Orchestra Hall. Extending from classics by Barber and Gershwin through William Schuman’s bold, robust Sixth Symphony to youthful Mason Bates’ cleverly crafted Violin Concerto, the program heard April 17 offered a resounding reminder of this country’s enduring contribution to orchestral music in the modern era.

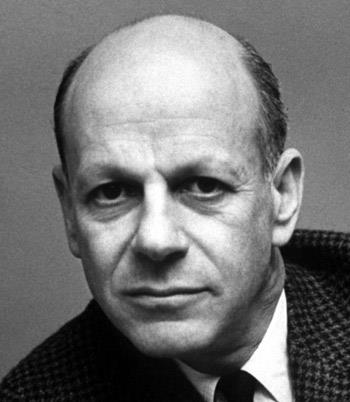

And it could be argued that no conductor has a better handle on classical Americana than the Los Angeles-born Slatkin. As this concert demonstrated to a fare-thee-well, the 69-year-old maestro, music director of both the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the Orchestre National de Lyon, resonates to the pulse and spirit that define our cultural temperament.

And it could be argued that no conductor has a better handle on classical Americana than the Los Angeles-born Slatkin. As this concert demonstrated to a fare-thee-well, the 69-year-old maestro, music director of both the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the Orchestre National de Lyon, resonates to the pulse and spirit that define our cultural temperament.

With violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, Slatkin presented the Chicago premiere of the Violin Concerto by CSO composer in residence Mason Bates. The conductor and soloist also gave the work its world premiere with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in December 2012, and their sharply focused, yet free-wheeling account of Bates’ densely wrought work bespoke thorough familiarity.

Cast in one grand arc spanning 30 minutes, the concerto might be viewed more as tone poem. In program notes, the 37-year-old composer explains that he took inspiration from a hybrid dinosaur-bird called Archaeopteryx. The prodigiously virtuosic concerto figuratively traces the creature’s evolution – or ascent – from earth to unfettered flight.

In that context, Bates’ concerto elaborates a single dominant musical theme as if through perpetual variation, ending in a breathtaking cadenza in which Meyers crowned a graceful, concentrated performance with a brilliant summary flourish. The evolutionary path to that point cast violin and orchestra in a kind of primordial duality, the whole musical force lurching forward through alternating episodes of earthy rhythms and ethereal lyricism.

Bates’ music demonstrated his idiomatic flair for orchestral writing – with dashes of his signature electronica imitated by conventional instruments – as well as his imaginative command of the violin as solo voice. To say Meyers played the piece as if she owned it would be merely redundant.

Bates’ music demonstrated his idiomatic flair for orchestral writing – with dashes of his signature electronica imitated by conventional instruments – as well as his imaginative command of the violin as solo voice. To say Meyers played the piece as if she owned it would be merely redundant.

Also new to Orchestra Hall was William Schuman’s bracing Sixth Symphony (1949). Sinuous and dark, it is a ringing expression of the post-war sobriety that generally stamped the arts in Europe as well as the U.S. Slatkin prefaced the performance with an illuminating commentary illustrated by orchestra excerpts, pointing out the traces of Schuman’s artistic DNA and recalling where this skilled and original composer fit in the American continuum.

In essence, Schuman (1910-1992) belongs to a forgotten generation of American composers whose worthy ranks include the likes of Peter Mennin, Roger Sessions, David Diamond, Paul Creston and Norman Dello Joio. What Slatkin did not say was that their substantial – and consistently appealing – works for orchestra were declared passé and effectively obliterated in the upsurge of post-Webern intellectualism that all but strangled American music in the 1960s and 70s.

Schuman’s virile and affecting Sixth Symphony is a shining example of what has been left behind. Constructed in a single 30-minute sweep with four well-defined internal sections evocative of the classical symphony, the work registers its modernist angst by setting comparatively simple elements in conflict with each other and casting individual sections – woodwinds, brasses, upper and lower strings – at odds with each other.

Schuman’s virile and affecting Sixth Symphony is a shining example of what has been left behind. Constructed in a single 30-minute sweep with four well-defined internal sections evocative of the classical symphony, the work registers its modernist angst by setting comparatively simple elements in conflict with each other and casting individual sections – woodwinds, brasses, upper and lower strings – at odds with each other.

Not only did Slatkin infuse this emotional churn with structural clarity and expressive purpose, but he also brought poetic sensibility to the symphony’s extended slow section, which in its almost tragic wistfulness drew Shostakovich to mind. The CSO responded all around with a performance of fiery urgency, precise rhythmic drive and lustrous textures. It was the Chicago Symphony’s first-ever performance of the Schuman Sixth, and the audience took the piece clamorously to heart.

Slatkin bookended these savory discoveries with two very familiar showpieces, in crackling performances of Barber’s “School for Scandal” Overture and Gershwin’s “An American in Paris.” So vibrant, buoyant and distinctly American was the latter that I couldn’t help thinking of it as a conductor in Paris – an American, of course, on exuberant break from his duties in Lyon. The CSO, led by the saucy trumpet of Christopher Martin, delivered a Red, White and Blue blazer. Or perhaps one should say Bleu-Blanc-Rouge.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at CSO.org

- Preview of the Chicago Symphony’s complete 2013-14 season: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

- A look ahead to Chicago Symphony’s 2014-15 season: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Tags: Anne Akiko Meyers, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, George Gershwin, Leonard Slatkin, Mason Bates, Samuel Barber, William Schumann